In early February, the former Ford Motor Company Assembly Plant in Richmond, California, hosted perhaps the greatest convergence of book makers in recent memory. Not the kind looking for a trifecta, but printers, typographers, paper makers, engravers, and binders—people involved in all aspects of traditional book arts. The assemblage of artists and craftspeople was remarkable even considering the range of expression of contemporary book work.

The old guard, those who work with vintage printing presses and type (sometimes casting their own hot metal) was well represented. And there were artists who use the printed form as a starting point for sculptural explorations of the interaction of words, images, and paper. They all come together thanks to the vision, energy, and commitment of Berkeley-based Peter Koch and Susan Filter.

Koch, a seasoned printer, and Filter, a paper conservator, established the CODEX Foundation in 2005 as a way to bring together stakeholders in the world of book arts. Their first symposium, a two-day meeting with lectures and a book fair, was held in 2007, and now convenes every other year in the San Francisco Bay area. This year, on the 10th anniversary of its founding, the CODEX events expanded to include a think-tank style meeting and their largest book fair yet, with 199 exhibitors and thousands of visitors.

A view of the CODEX Book Fair, 2015

A view of the CODEX Book Fair, 2015The majority of the participants were from the United States, with heavy concentrations from areas with strong book arts traditions, such as Northern California and New York City, but representation was seen from across the nation, from Arizona to Wisconsin to Virginia. Makers came from Argentina, Australia, Austria, Japan, New Zealand, and Russia. Seven presses from Mexico were in attendance, reflecting the influence of CODEXMexico, an affiliate group that held its inaugural conference in Mexico City in 2012. (CODEXAustralia was established in 2014, but is currently on hiatus as they transition into CODEXAntipodes.)

Also in residence were representatives of organizations that provide support and resources: The San Francisco Center for the Book Arts, The Center for the Book Arts, New York, and The Book Arts Foundation from South Korea—along with a few academic printing programs: Mills College, Columbia College Chicago, Colorado College, and Florida State University.

Among the exhibitors were a number of printers with years of experience and significant bibliographies of published works, including the Janus Press from Vermont, founded by Claire Van Vliet and still going strong after fifty years; Edition Schwarze Seite, a German press that has a strong interaction with artists in Nicaragua; and Midnight Paper Sales, Gaylord Schanilec’s imprint that has produced a number of works on natural themes—including trees, mayflies, and his latest work, Lac des Pleurs, Report from Lake Pepin—the seven-year gestation of which is recorded in a blog.

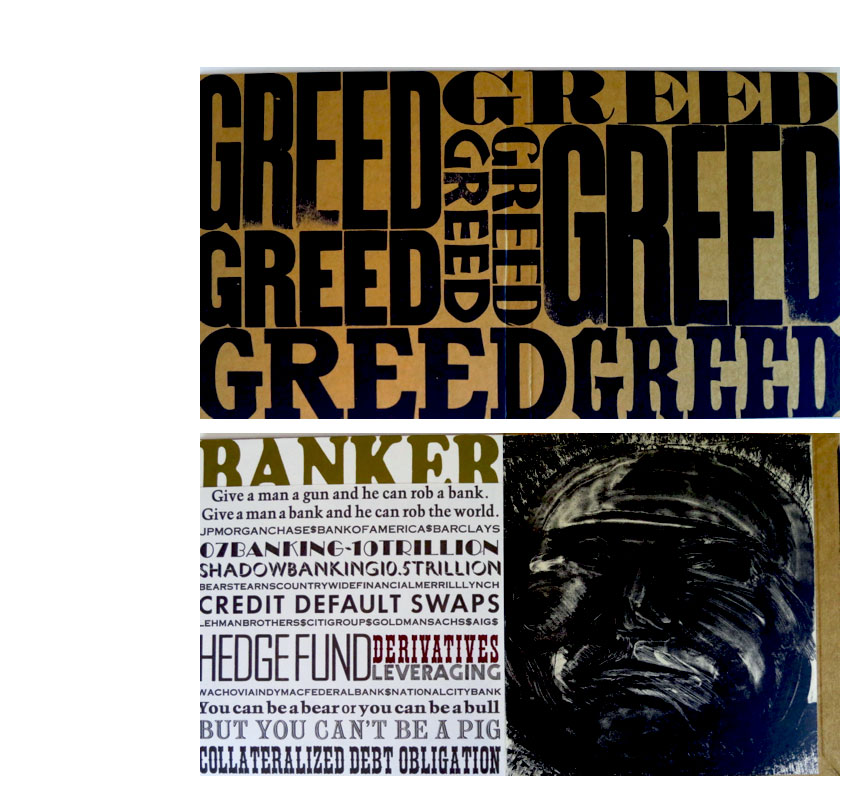

Pages from Greed, Janus Press, 2013

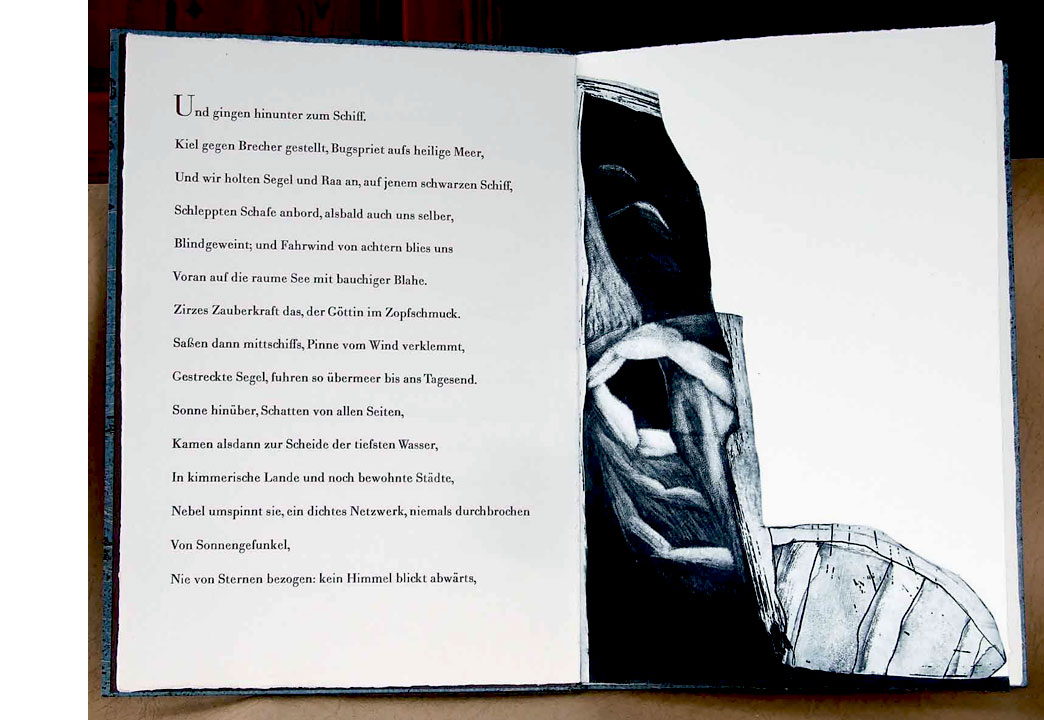

Pages from Ezra Pound, "Canto 1," Schwarze Seite Press, 2001

A mix of innovative and classic works were on display from Brighton Press, San Diego; The Salvage Press, Dublin, Ireland; In Cahoots Press, Oakland; members of Shift-Lab, a collective from Sugar Mountain, North Carolina; Donna Westermann, also from Oakland; and Two Ponds Press, from Rockport, Maine.

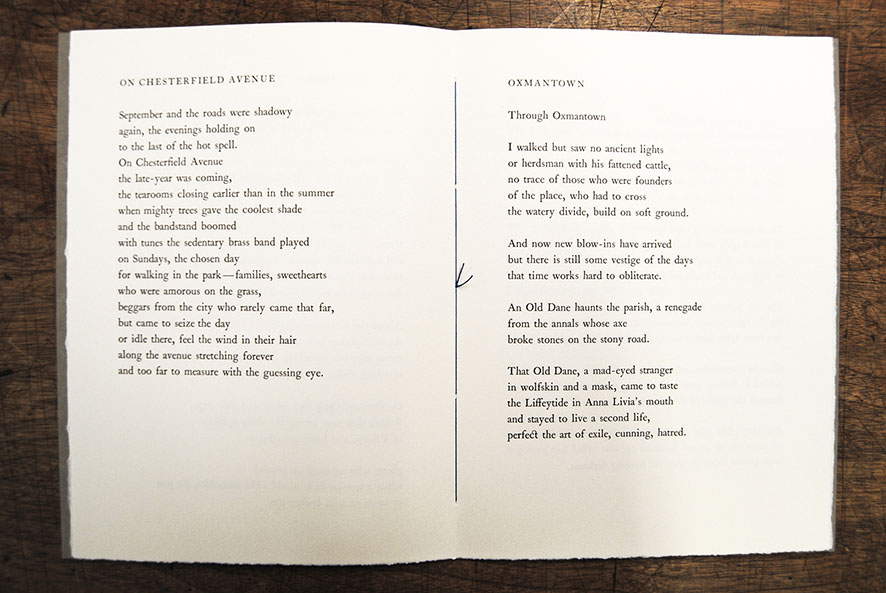

Pages from Gerald Smyth, We Like It Here by the River, Salvage Press, 2014

Pages from Gerald Smyth, We Like It Here by the River, Salvage Press, 2014

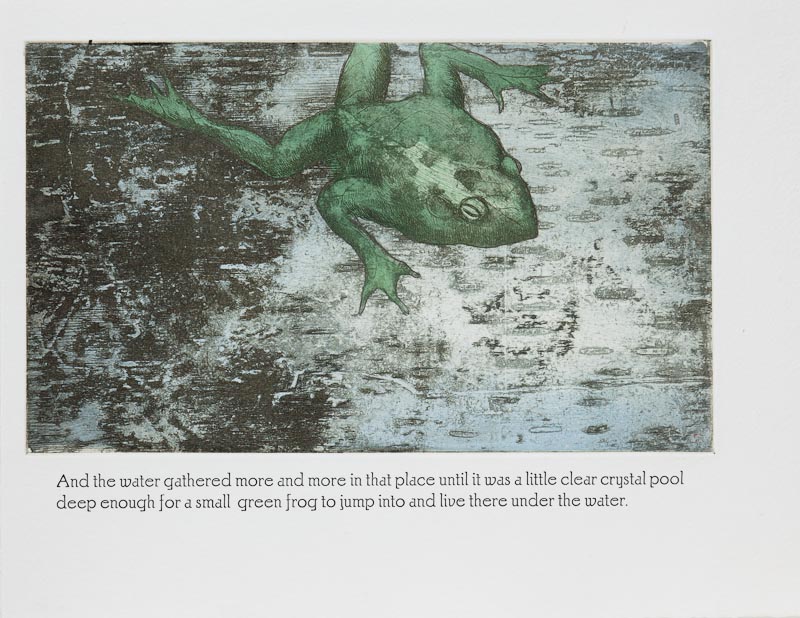

Page from Margaret Wise Brown, The Little River, with illustration by Michael Kuch, Two Ponds Press, 2012

Many of these “presses” are, in fact, single person operations, artists working by themselves in home studios or small workshops. Some may have the occasional assistant or apprentice, but their work is similar to that of painters and sculptors—it may take years to complete a book – from first conception, through trial printing states, to final binding or boxing. A prime example is Claire Illouz, trained in etching in Japan, who produces books combining images of vegetation and household objects with poems by people she admires. Of a similar vision is Sarah Horowitz. Her most recent book is Lepidoptera, which combines the text of Virginia Woolf’s “The Death of the Moth” with Horowitz’s etchings of winged specimens from the Oregon State Arthropod Collection. A video tour of Claire Illouz’s The Wayfarer, 2011, can be found here.

Title page from Sarah Horowitz, Lepidoptera: The Death of A Moth, Wiesedruck Press, 2014

The range of projects on display probably had many visitors asking themselves where the line could be drawn between printing and fine art. A form of this question was discussed at length at the CODEX Collegium, the meeting preceding the book fair in which I participated, hosted by Stanford University. It is central to a discussion that happens at libraries and museums around the world: what do we call these things? Hand-printed books? Fine printing? Artists’ books? Livres d’artistes? What if the book is not, in fact, bound, as one sees often in productions from France—where the book is presented as loose sheets in a clamshell container? Does there need to be textual content, however minimal? How close to the form of a codex should the thing be? (Tamar Stone’s “Asylum – Institution – Sanitarium,” a meditation on nineteenth-century definitions of mental illness is in the form of a doll bed, fitted with sheets embroidered with texts.) I suggested, in purely good humor, that the catalog entry should be “cool books”—since that is what students ask for after I’ve introduced them to such works: “Show us more cool books!”

No matter what the answers to these questions turn out to be, the good news is that they are being discussed by a community of artists, printers, librarians, curators, and collectors who are happily inclusive of the wide range of expressions of traditional and, in many ways, non-traditional book arts. That world is small enough that there is a consensus of support.