Another in a series of food-related posts, published in anticipation of Design Observer's upcoming conference exploring the intersection of design and food. Tickets can be purchased here — and they're selling quickly, so don't wait!

++++

Do you remember the first time we were served a slice of a cake with a photograph on it? Not an artistically rendered one, but an actual photo—created on an inkjet printer using edible inks and frosting sheets made from food-quality starch. What was novel ten years ago is a standard menu item from most grocery stores and bakeries. (So ubiquitous that they have lost their wow factor.)

++++

Do you remember the first time we were served a slice of a cake with a photograph on it? Not an artistically rendered one, but an actual photo—created on an inkjet printer using edible inks and frosting sheets made from food-quality starch. What was novel ten years ago is a standard menu item from most grocery stores and bakeries. (So ubiquitous that they have lost their wow factor.)

Going one step further, Sanryu, a Japanese technology company, has been developing flatbed printers that can print directly on food products such as cookies and bread, eliminating the messy transfer process.

Even more versatile is TagOnThat, a recent Kickstarter-funded business, that offers a couple of models of machinery that can put designs on a variety of shaped surfaces—including food—using a stamp transfer process. They even boast kosher inks!

The most amazing advancement in the food-printing matrix are 3-D printers that actually print with edible foodstuffs (pancake batter, sugar, or chocolate). This may seem like a novelty, but the practical uses when the technology matures will be very important for feeding people in isolated places (think military troops and astronauts).

But as far as printing images on food goes, one of the oldest and simplest practices survives in the central mountains of Mexico. A small sub-group of the Otomí people in the state of Guanajuato have been putting images on tortillas for at least three centuries. The importance of corn to the indigenous people of the Americas is exemplified by the tortilla—that simple, but indispensible and ancient staff of life. As Spanish missionaries converted native inhabitants to Catholicism in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, many examples of syncretism between long-established indigenous views on nature and the new theology emerged. Ceremonial tortillas were one of the most intriguing to survive to present times.

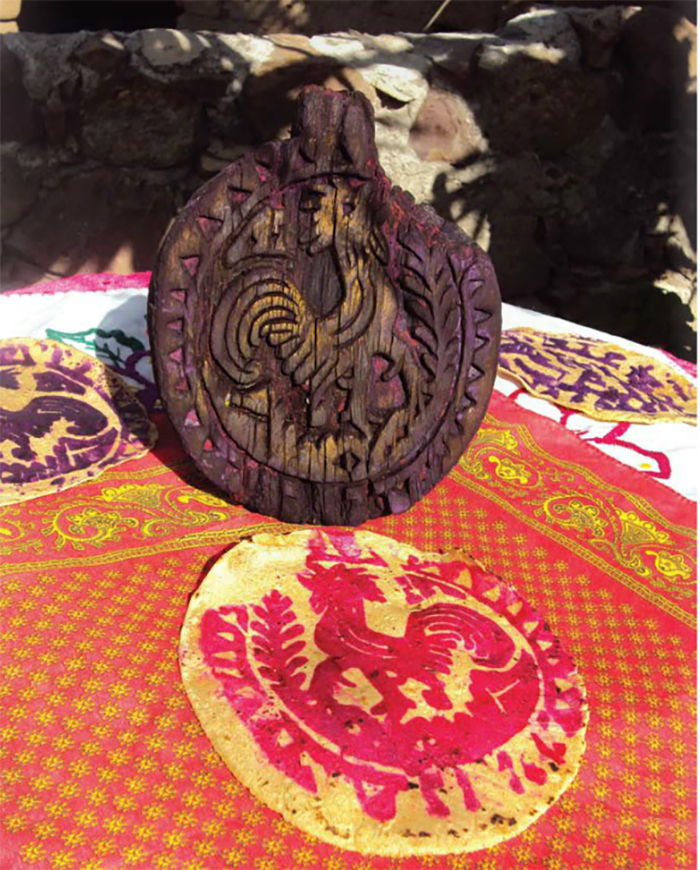

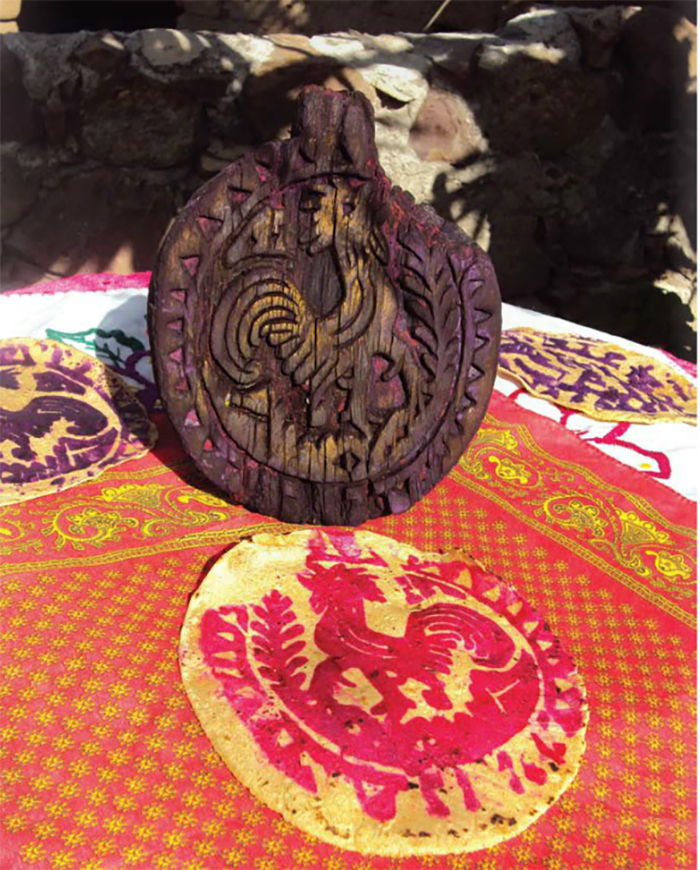

A vividly colored volume produced by Ediciones La Rana in 2010, Tortillas Ceremoniales (by Juárez Ramírez and Karina Jazmín) explores the history of this beautiful food printing phenomenon. (Images used here are taken from that book, an online version of which is accessible here.)

Tortillas are prepared by the women of the Otomí communities along the Laja River in Comonfort and San Miguel de Allende, as they have been for generations. The process is basic: a round piece of mesquite wood (used for its hardness and resilience) is carved with an image in relief and sanded slightly to make a flat surface. Corn tortillas are made by hand, then cooked partially on a griddle. The surface of the wooden design is inked using a pigment made from either honeysuckle or cochineal, applied by a dried corncob. The tortilla is pressed against the surface to pick up the inked design, and then is returned to the griddle to cook for a bit longer and fix the image. (While this process follows the basic definition of printing, the Otomí refer to it as “painting.")

Because these tortillas are made principally for religious observances, they are referred to as ceremonial. The images they carry are derived from religious and natural observances: crosses, saints, animals, plants. During very important religious feast days, such as February 2, Candelaria, these tortillas are used to festoon large crosses, or suchiles, created for the holiday. But in general, they are meant to eaten—to provide sustenance to celebrants and at the same time remind them of their connection to the earth and to the heavens. It is easy to see a connection between ceremonial tortillas and communion wafers and communion bread, other edible round items that are often blind stamped with religious designs.

These tortillas play a core role in the lives of the Otomí and their heritage, their encounters with and acculturation into, European belief systems, and their historic and continuing relation to the vital sustenance of corn crops.

The practice is such an central part of the lives of the Otomí people that tortillas are often now made for secular occasions—birthdays, Mother’s Day, and engagement parties. In this manner, they do have a link to those gaudy photo-decorated birthday cakes from the supermarket. Both of these “printed” foods are ceremonial, in their fashion, though the tortillas have a deeper spiritual connection to their makers and their consumers.