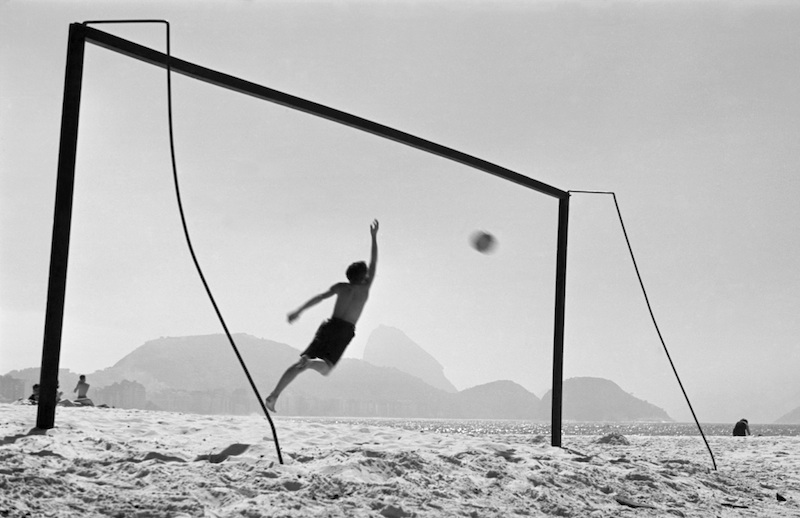

Copacabana Beach, Rio de Janeiro by Thomaz Farkas, 1947. Collection: Instituto Moreira Salles

I had only been in São Paulo a few hours when I learned about Thomaz Farkas from his son Kiko Farkas, a well-known graphic designer. Born in Budapest, Farkas (1924-2011) emigrated to Brazil with his family in 1930. When he was eight his father gave him a camera, and while still in his teens, Farkas joined the Foto Cine Clube Bandeirante. A survey of work by the influential club (founded in 1939), featuring pictures by Farkas, is now on view at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo.

“Almost everything in my photography of that period was constructions with light and shadow, whether landscapes, objects or still life,” he recalls in the catalogue Thomaz Farkas: Memories and Discoveries (2014). “It looks as if I was afraid to shoot people.” A key figure in the growth of modern Brazilian photography, he took a particular interest in architecture, applying an exacting abstractionist eye to the repetitions and rhythms of windows, tiles, ceiling lights, and railings observed in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. His time in Rio gave him new insight into life in Brazil, and he would go on his own to the beaches in search of subjects to photograph.

There are two versions of Copacabana Beach, representing both the earlier formalist Farkas and his later interest, as a photographer, in people. In the first, published in 1948 in a feature about his work in Iris magazine, the goal mouth is empty, concentrating attention on the taut architectural shape of the frame. In the layout he designed, Farkas surrounds the image with material details of buildings, wires, and utility poles. The “activated” version of the picture, which emerged later, is more satisfying. The goalposts and their metal support poles still register as dark graphic lines inscribed on the sheet of the sky, but the presence of the boy leaping toward the pale distant mass of Sugarloaf Mountain, his leg forming a perfect “V” with the frame, brings the scene rapturously to life. Is he flinging the ball for the joy of it, or making a vain attempt to stop a shot at the goal taken by a friend who is positioned outside the picture? Farkas intercepts the blur of the flying projectile with geometrical precision.

The beach became world famous in later decades as a destination for vacationing sunseekers, and for its spectacular New Year’s Eve celebrations. Probably lying down and holding his Leica just above the sand, Farkas makes a touching record—before international tourism and glitz took over—of a refuge next to the ocean where the local kids go to play ball, and everyday life (this part, anyway) just happens to resemble paradise.