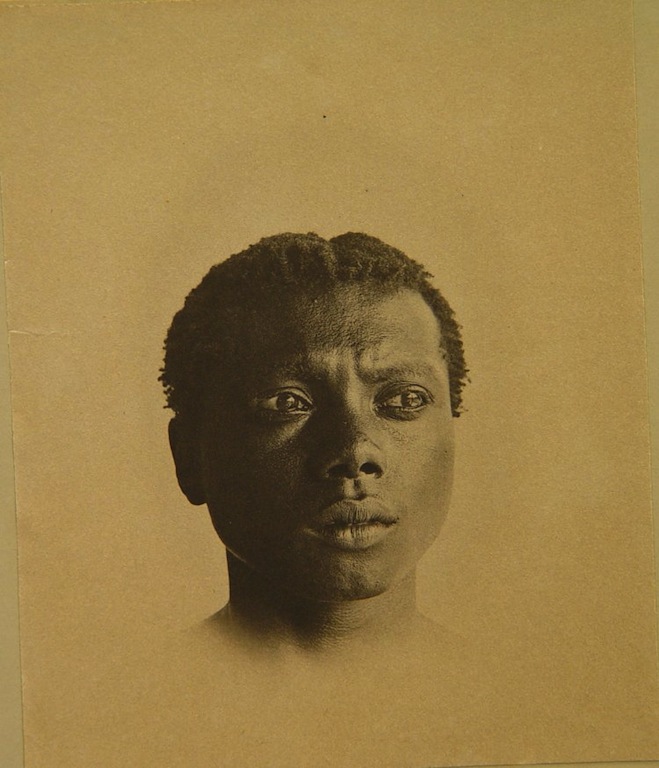

Middle Andaman Islander by Maurice Vidal Portman, 1890s. © Trustees of the British Museum

Anthropological photographs, especially those taken in the early decades of the discipline, often make for uncomfortable viewing. Anthropologists believed themselves to be engaged in a disinterested project of universal scientific insight and value, but their relationship to the people they photographed and classified was often that of a colonial power occupying the territory of the “savages,” as they saw them. The presumption of racial inferiority is seared into these pictures, and the unease of the indigenous people submitting to inspection is often plain to see. Sometimes there are other dubious undercurrents, such as a tendency, knowingly or not, to eroticize the subjects.

In the 1890s, when he took this picture, Maurice Vidal Portman (1860-1935) was “officer in charge of the Andamanese” in the Andaman Islands, in the Bay of Bengal in the Indian Ocean. Much of his time was spent not on administrative duties but in photographing the people of the archipelago; he was engaged in making at his own expense a compendious, never to be finished “Record of the Andamanese” for the ethnographic department of the British Museum in London. The picture from the museum’s collection belongs to an album of twenty-five portraits of men and women, showing only the head and shoulders against an empty background. The subject is a man named Balia, aged about twenty-five, a member of the Aka Bojigiab tribe from Middle Andaman Island. It is a hauntingly beautiful image.

Portman is a mysterious figure, whose private motivations remain cloudy, but he did leave a precisely detailed account of his methods when making pictures. In 1896, he published a paper titled “Photography for Anthropologists” in The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, where he describes himself as “a practical anthropological photographer,” and notes his “sixteen years’ experience with savages.” The pursuit of visual ethnography requires accuracy, he instructs, not delicate illumination and picturesque scenes. When making a portrait, the lighting should be even, without highlights and heavy shadows, and “the body must be upright, and the face so held that the eyes looking straight before the subject are fixed on an object on a level with them.”

In the early days of anthropology, researchers were obsessed with calibrating the facial and physical differences between races, and that was presumably Portman’s purpose with his studies of “typical heads.” Yet the picture exceeds and subverts its ostensibly scientific intentions. Portman has ignored his own advice about lighting the face evenly, and the tonal contrast intensifies its apparitional presence. The young man’s gaze may be fixed on an unseen object, as Portman prescribed, but his expression is striking for its inwardness. There is sadness, perplexity and perhaps anger in his eyes and knitted brow, and a hint of something unsaid in the slightly parted lips. Portman was both concerned “father” and sometimes brutal oppressor to the Adamanese, among whom he chose to live for many years. Whatever its cause, the tenderness of the image is unmistakable.