From left, ARO partners Stephen Cassell, Kim Yao and Adam Yarinsky. Photo: Lajos Geenen

On October 20, Architecture Research Office will be presented with the 2011 National Design Award for Architecture Design. ARO, founded in 1993 by Stephen Cassell and Adam Yarinsky, is a New York–based firm with an exceptionally broad portfolio, ranging from creating new guidelines for design excellence in the federal government to renovating Donald Judd’s Spring Street studio, with theaters, synagogues, and a new dormitory for Tulane University in between. ARO — which added Kim Yao as a third partner earlier this year — is perhaps best known for participating in the Museum of Modern Art’s “Rising Currents" exhibition, for which the group studied managing climate change on the streets of Lower Manhattan. Alexandra Lange spoke to Cassell and Yarinksy on October 11 about the award and their work for New York City.

Congratulations on the National Design Award. Can you be self-analytical and talk about why you think you won this year, as you have been finalists in the past?

Stephen Cassell: One of the positive things, aside from the stress of the recession, was it gave us time to focus our work on larger-scale research projects. We had always worked at the scale of buildings, with materiality, and it was time to expand how we were thinking about the city. There was a three-year period where the Latrobe competition, “Rising Currents” at MoMA and the Greenwich South study all hit.

Adam Yarinsky: I think there’s a growing acknowledgment that the kind of practice we have is potentially a good model for architects. I know a lot of our peers are already practicing this way, but it is an indication that architecture can be socially engaged. It can be about issues, and can have cultural consequence, but can also be thought about as collaborative and as deriving its direction from the world around it.

But you also don’t want to be saying, “We’re not interested in how it looks.”

Cassell: No, we are really blunt about that: it has to look beautiful. It sounds really old-fashioned.

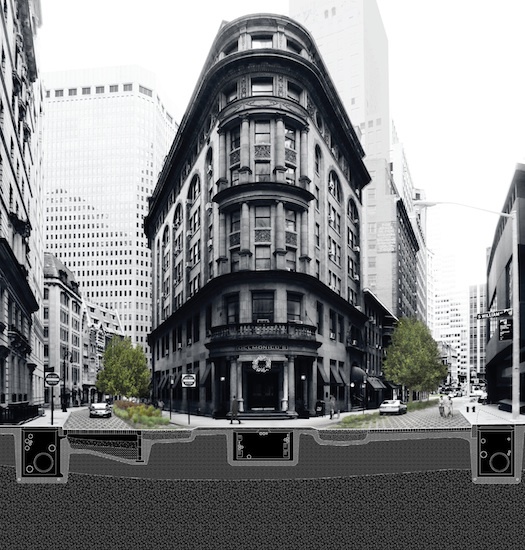

View of Greenwich South, 41-acre site below Ground Zero

The projects seem to be clustered on opposite ends of the spectrum. On the one hand you are working on this huge planning project for Greenwich South, and on the other hand, on very small, very nice things like Union Square or a new entrance pavilion for the Brooklyn Botanic Gardens. Is that by choice or is that how things fall out?

Yarinsky: We got our start as a firm doing exhibition design for the Cooper-Hewitt, the AIA, the Asia Society. That was our initial foray into public work and we wanted to do more of it.

Cassell: When we worked on the Prada store with OMA or those super high-end houses, those were fun but not fulfilling. They are part of architecture but not all of architecture. We purposely have a wide range of projects in the office. The range has gotten wider over time, but it is something we had from day one.

Reading garden, Susan P. and Richard A. Friedman Study Center, Brown University, Photo: Paul Warchol

And they are not always so dissimilar. I think about the way we are talking to the Flea, trying to understand what they are, who they are and pragmatically how they work so we can design around that. That sort of analytical thinking, while it isn’t identical to Greenwich South, there are a lot of similar underpinnings. A lot of it is about research and how you frame the problem. The other half of that is the recession. When there is no money to build, you plan. And so we did programming studies for the Cornell school of architecture and planning. We’re doing a lot of those.

Yarinsky: We’re now on our fourth architecture school.

That’s very funny.

Cassell: For the schools, it is always the same problem: we don’t have very much money, but how can we rethink the way we are working?

Yarinsky: And how can we take an existing structure and bring it into the future? Or you look at the Princeton architecture school. We did a capital improvement project to get the school to be ADA-compliant and also have it meet fire code in order to have it pass accreditation.

Cassell: Given the crossover with some of those planning studies, we realized we could get paid just for this! There is strategic thinking on how to do more with less. The Graduate School of Design at Harvard is not going to build a new big building. Architecture schools have historically not had the big fundraising, except for the three people who became developers. Working with them involves realizing you can make a place a lot better without building anything.

School of Architecture addition, Princeton University. Photo: Paul Warchol

I would like to hear more about your project for the General Services Administration, creating a national strategy for excellence in design. What does that mean, and what does that entail?

Yarinsky: We are two-thirds of the way through the project, I can’t give you a lot of detail, but we are leading a team with Mark Robbins and HR&A Advisors and we are finalizing the report we are going to give them. It will be a book coming out in the spring that Pentagram is designing that will be a tool for communicating how to promote design quality to other agencies of the federal government.

R-House, Syracuse, NY. Photo: Richard Barnes

Cassell: Some of it is just trying to make sure people frame problems properly.

Yarinsky: In the writing community there was this sense that we need a national design policy, and anyone who has been looking at what’s happening in the government in the past few years realizes that is impossible, but also might not be such a good idea. In the UK, CABE was erased when the new government came in. Our study says that we are doing it already, so how do you make it happen more, and how do you decentralize it so that it becomes part of the DNA of all these organizations, not a policing activity or an uber-commission that controls everything? We think that will give it more legs.

Is any of it just plain architectural education? Like, “These are examples of good government architecture and here is why.”

Yarinsky: The current format is for volume one to be a history of design in the federal government, as both the GSA and NEA have well-documented histories. For the GSA the defining moment was Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s principles for federal architecture. As Casey Jones [GSA Director of Design Excellence and the Arts] says, these guidelines were not really adopted until the GSA incporated them into the Design Excellence program. The NEA haven’t been around as long, but they have a long history of partnering with federal agencies. That will set the context and say design is strong.

The second part is recommending specific programs across three or four category areas, focused on how a project happens. That says, “You are doing this anyway, so here is where you can actually improve design.”

Cassell: An example might be if a transportation infrastructure project is happening in a city, realizing that if the project is planned properly and conceived properly, you can leverage a lot better city from that.

Yarinsky: A great example of what the federal government is doing now is the Partnership for Sustainable Communities, which is HUD, DOT and EPA. The idea is to go beyond DOT saying, “We are getting you from point A to point B. To think about the strategic location of a road, but also where that investment might best be used, for housing, in terms of environmental quality." How do you take initiatives like that and make that the norm? How does leadership encompass more holistic thinking?

Another very large-scale project is the vision and framework for Greenwich South, a section of lower Manhattan just south of the World Trade Center site. Can you tell me some of the history of that plan, which you created for the Downtown Alliance?

Cassell: The lower half of the area is the tunnel entrance and the New York Athletic Club, the upper half is classic lower Manhattan fabric. I grew up over here, on the east side, and there were streets in that area I had never walked down.

We were leading a team with Beyer Blinder Belle and Scott Stowell of Open for communication and graphics. We said what we would like to do is to propose a framework, rather than a master plan, because the area is way over-master-planned.

Greenwich South proposal for park over entrance to Battery Park Tunnel.

The first part of the study was an intense research period, with classic zoning analysis. We found a lot of unused FAR, in the range of 8 to 12 million square feet, enough for three major building sites. Part of that would be created by decking over the tunnel. We also had a big brain trust dinner, where we wanted to hear from people who weren’t architects and planners. We gave a little presentation, saying you could argue the whole history of the neighborhood is being imposed with massive infrastructure projects and then rebounding, starting with an elevated train line, then the tunnel, and then the World Trade Center.

Yarinsky: There is a building down there that has an escalator to get to a second-floor level that would have continued the podium of the World Trade Center. That was a grand vision that was never executable.

Cassell: Comments we got from that session were things like, “Don’t make it too pretty.” I don’t know if that was a subtle swipe at Battery Park City or not. Another person said, “Every time I walk out the door, I head uptown.”

The next step was creating a framework, a set of five or six rules that are almost purposely broad. One is connect the east and west, since the neighborhood has a lot of dead-end streets. Each rule had a specific set of sub-strategies: here are three or four major things you can do, and here’s what we mean by connecting east and west. One of which would be dealing with West Street. We said bridges are a bad idea. This street is actually the width of Park Avenue, so we should be able to make this work. There is a street that is 12 feet wide, Exchange Place, as well as other streets with almost no traffic. You could program them for food trucks. Or you realize Greenwich Street is the only street that will connect through from north to south. You could think about a Lower West Side — that you could walk from the High Line all the way down through a series of vibrant neighborhoods to the end of lower Manhattan. How do you program for that?

After we came up with the draft we brought in nine other designers and gave them assignments, some of which were overlapping, which fell into short-term, medium-term and long-term. That was a way to get feedback, and a way to generate visual content. Work AC came up with the Plug In Tower, which is not going to get built, but it is smart and crazy at the same time. It made it possible for us to provide visualization for the study without fear.

The end of this was we put an exhibit up in Zuccotti Park. So we can say we were predecessors to Occupy New York.

Open-air exhibit marking the debut of Greenwich South study, Zuccotti Park, New York. Photo: Frank Oudeman

Were you already working on your research on Lower Manhattan and climate change when the Downtown Alliance asked you to work on Greenwich South?

Yarinsky: That was a nice coincidence. Our work on climate change issues came with a competition we won for the History Channel called City of the Future. We had a week to design what Manhattan would look like in 100 years. We chose to look at parts of the city that would be flooded as the water level rose and create a narrative of design for that.

We came up with this new typology of pier-like buildings that would occupy the flooded city. At the same time, Guy Nordenson was applying for the Latrobe Prize, and he was interested specifically in the upper harbor of New York and New Jersey and how climate change would affect them. He asked us to join his team. Later he pitched that to [MoMA’s chief architecture and design curator] Barry Bergdoll, and that became “Rising Currents." We didn’t tell Greenwich South what was going to happen to their neighborhood in 50 years.

View of ARO and dlandstudio's New Urban Ground proposal for "Rising Currents."

Infrastructure for a soggy Hanover Square in downtown Manhattan, for "Rising Currents."

Perhaps because you had worked on the topic the longest, I thought your proposal for how to rework the streets of lower Manhattan was among the most developed in the exhibition, as well as the easiest for people to understand. I thought, "Why aren’t we doing this now?"

Yarinsky: We took something known, a way of handling storm water runoff, but it had never been conceived of at that scale and in that densely populated area. Just to show the implications of that is a very straightforward thing that can be revelatory. We also told ourselves, We are designing public space; we are not designing buildings. The prior history of visionary projects for Manhattan is amazing building types and tunnels and bridges in the sky. Barry was very good about helping to frame and critique everyone. He said the ideas should be too realistic to dismiss, but provocative enough to keep people engaged.

Cassell: We decided we should do everything we can not to draw the building of the future. There are enough buildings here. And then we asked Susannah Drake to collaborate, and she came with such a deep knowledge with the Sponge Park. The Latrobe book was called On the Water, but “Rising Currents” was in the water. We were trying to design the city to be flooded.

Did you go down to lower Manhattan during Irene?

Cassell: We were really worried because we knew what the storm surge could be. With the storm aligned with high tide, the surge can be 18 to 20 feet.

Yarinsky: We got lucky because that storm died down to a tropical storm by the time it got here.

Last question: I wanted to give you the opportunity to highlight a built project, rather than a study.

Yarinsky: Restoring the Donald Judd house has been really exciting and exemplifies our approach to architecture. In this case, it is done with a lot of desire that our effort be effaced when we are finished. That’s under construction right now, and will open spring 2013. I am one of these people who has never been really into X architect. So this was a great opportunity to be engaged and solve their problem, but also to learn about Judd. There is a real subtlety and relation between the building context and his work that will be something that can be presented to the public now.

Entry Courtyard, Martha's Vineyard house, Chilmark, MA. Photo: Thomas Brodin

Cassell: The Tulane dorm is really exciting for us in terms of scale, since it will be a new building and it is a great campus. We just started programming for that. We also just finished schematic design for CBST, which is (as they bill themselves) the world’s largest gay and lesbian synagogue. We have been working with these guys for five years now, helped them find their site in a Cass Gilbert box. I was just at their Yom Kippur service, which they do at the Javits Center. There were 2000 people there. It is always free, open to anyone, you don’t need a reservation. They always told me the sun going down as service starts was really beautiful, but there was also a helicopter hovering just behind the rabbi. It was an only-in-New-York juxtaposition.