Johann Heinrich Muntz, Strawberry Hill, c. 1755-59 (via Some Landscapes)

After my last post on the uses of architecture in Austen, I got a lot of reading suggestions. The one that immediately piqued my interest was from Will Wiles, an editor at Icon and the author of the forthcoming Care of Wooden Floors, an architectural satire that sounds like the sort of archi-Austen comedy of manners I am always telling myself I should write. But he's actually done it.

He said Vladimir Nabokov had written on Austen's Mansfield Park, complete with diagrams of manor and gardens. Diagrams! I was sold. And indeed, it had slipped my mind (until @amlblog reminded me) that Mansfield Park includes the most explicit discussion of design in Austen's books, via ongoing, gentlemanly discussions of improvements to the estate. Other Austens treat the sublime and the picturesque, but Mansfield Park links the matrimonial planning of the ladies, to the landscape planning of the men.

MP is a perennial also-ran in the Austen sweepstakes, since its heroine, Fanny Price, is generally considered a drip. When the queens of costume drama got around to MP, director Patricia Rozema had to rewrite her character, and add feminism, rain and post-colonial politics, before she felt she had something worth filming. I think the problem isn't Fanny, but the unromantic ending. How could the author of scenes of such supressed sexual tension as those between Darcy and Elizabeth Bennet, Wentworth and Anne Elliot, not give Fanny her heart-shaped moment? Even Elinor in Sense and Sensibility (which I rank lower than MP) gets a good cry!

But it is precisely the dominance of transactions, rather than romance, that makes Mansfield Park such a good vehicle for planning of all kinds.

Nabokov truly appreciates MP, and offers a defense of Austen's limited view that haters like Mark Twain and V.S. Naipul would do well to read. He writes,

An original author always invents an original world, and if a character or an action fits into the pattern of that world, then we experience the pleasurable shock of artistic truth, no matter how unlikely the person or thing may seem if transferred into what book reviewers, poor hacks, call "real life." There is no such thing as real life for an author of genius: he must create it himself and then create the consequences.

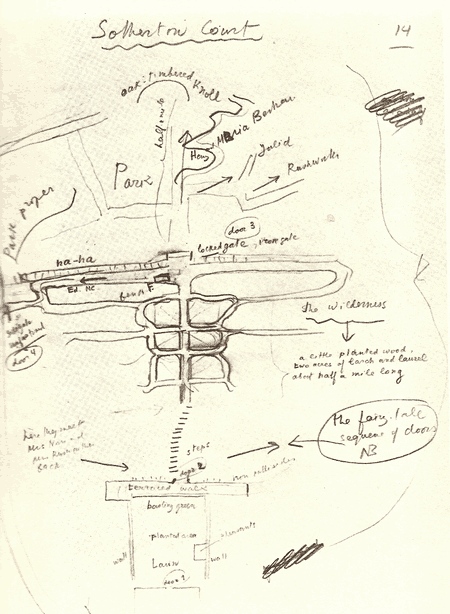

Vladimir Nabokov, Sotherton Court

And thus: diagrams. Nabokov acquaints himself first with the geography of England, mapping the action from Northampton to Hampshire, to Portsmouth, to London. He also draws the plan of the house Mansfield Park, to better understand its transformation into an ill-fated private theater. And most importantly, he diagrams the garden at Sotherton Court, scene of the novel's greatest set piece of interpersonal and geographical misalliance.

The most famous line, explicitly connecting the emotional and the physical states of our anti-heroine Maria Bertram is hers:

"Yes, certainly, the sun shines and the park looks very cheerful. But unluckily that iron gate, that ha-ha, give me a feeling of restraint and hardship. I cannot get out, as the starling said."Austen creates teams in relation to the landscape, the traditionalists versus the modernizers, of which Fanny is firmly in the former camp. As Nabokov writes,

During the discussion about improving estates, Rushworth observes that he is sure that Repton would cut down the avenue of old oaks that led from the west front of the house in order to provide a more open prospect [a change in landscape style, from the formal to the faux-naturalism passed all the way to Olmsted]. "Fanny, who was sitting on the other side of Edmund, exactly opposite Miss Crawford, and who had been attentively listening, now looked at him, and said in a low voice, 'Cut down an avenue! What a pity!...'Such improving, however, was the mark of the educated man. Later in the book, the possibility for betterment at Edmund Bertram's future house at Thornton Lacey is used as a sort of proof of status. An estate worth improving, this scene implies, is an estate worth having (and thus Edmund would not be such a bad catch for MaryCrawford, who is determined to resist second sons).

Nabokov has much more to say, and for an Austen fan, his takes on the various terrible characters in this book are a particular highlight. For me it was a pleasure to re-read this novel through his eyes, as well as with an eye to the landscape. For Austen's readers, all these detailed suggestions must have seemed very specific to the time, indications of style as choice of shoe, or car, or phone would be in today's novel. Since minimalist satire is taken, maybe I need to look closer to home, and my novel should spoof the search for zen gardening in a Brooklyn backyard.“Well,” continued Edmund, “and how did you like what you saw?”

“Very much indeed. You are a lucky fellow. There will be work for five summers at least before the place is liveable.” [This is Henry Crawford, Mary Crawford's brother, and an interested party.]

“No, no, not so bad as that. The farmyard must be moved, I grant you; but I am not aware of anything else. The house is by no means bad, and when the yard is removed, there may be a very tolerable approach to it.”

“The farmyard must be cleared away entirely, and planted up to shut out the blacksmith’s shop. The house must be turned to front the east instead of the north— the entrance and principal rooms, I mean, must be on that side, where the view is really very pretty; I am sure it may be done. And there must be your approach, through what is at present the garden. You must make a new garden at what is now the back of the house; which will be giving it the best aspect in the world, sloping to the south–east. The ground seems precisely formed for it. I rode fifty yards up the lane, between the church and the house, in order to look about me; and saw how it might all be. Nothing can be easier. The meadows beyond what will be the garden, as well as what now is, sweeping round from the lane I stood in to the north–east, that is, to the principal road through the village, must be all laid together, of course; very pretty meadows they are, finely sprinkled with timber. They belong to the living, I suppose; if not, you must purchase them. Then the stream—something must be done with the stream; but I could not quite determine what. I had two or three ideas.”

“And I have two or three ideas also,” said Edmund, “and one of them is, that very little of your plan for Thornton Lacey will ever be put in practice. I must be satisfied with rather less ornament and beauty. I think the house and premises may be made comfortable, and given the air of a gentleman’s residence, without any very heavy expense, and that must suffice me; and, I hope, may suffice all who care about me.”