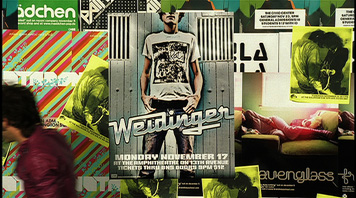

Fake posters for cokemusic.com commercial, Brand New School, 2007

The Cinematic Orchestra's latest album, a recent Very Short List missive informs us, is a movie soundtrack for a movie that was never made. The fact that this album lacks its external referent prompts the VSL reviewers to speculate gleefully on the existence of other content-less formats: "Dazzling book jackets without novels inside; awesome stage sets on which actors never set foot; kick-ass magazine covers with no accompanying articles...we love the myriad possibilities of this new cart-before-the-horse genre."

In fact, the signs of this "cart-before-the-horse genre" are already evident, especially within the time-honored discipline of poster design.

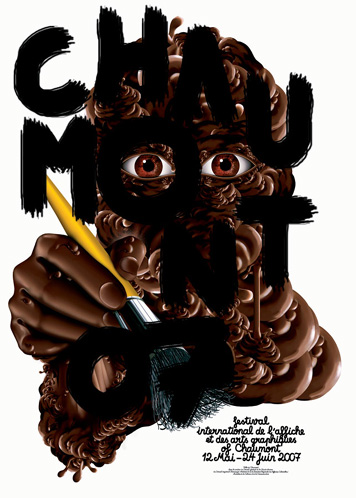

Student work on display at the Chaumont Poster Festival, 2007

One weekend last summer I was a juror for a poster competition in the remote hunting town of Chaumont in the Northeast of France. For the duration of a few weeks each summer the entire town is overtaken by poster fever. All the main buildings—including a bus garage and a Jesuit chapel—are filled with poster exhibitions and the bakers, grocery stores and pharmacies strive to outdo one another with their poster-themed window displays. Even the local bar is called L'Affiche.

Poster for the Chaumont Poster Festival, Mathias Schweizer, 2007

Despite the fact that we live in an era of viral and multi-platform marketing, posters still excite a peculiar intensity of passion among their makers and their beholders. The poster represents for graphic designers a powerful and alluring force—a rectangular arena in which to exercise their most expressive, experimental and potentially significant work. Perhaps it is because it was so much a part of graphic design's emergence as a discipline in the late 19th-century that the poster is still considered the sacred cow of graphic design. The poster remains what the stage at the Old Vic is to actors, a form through which to measure oneself against greatness.

The other 5 jurors and I spent a long day pacing around the interior of an old warehouse viewing 117 posters, pre-selected from almost 2,000 entries. Our progress was slow since each of us spoke a different language and the text on the posters in this international competition was in 20 languages. Several times our deliberations were brought to a complete halt when we came up against posters that, even after we'd translated them to everyone's satisfaction, still felt mysterious and empty.

At first glance these posters seemed like the others: they had the same proportions, they were professionally executed and had devices that look liked logos on them. Many of them were visually compelling. What was odd about them, we soon realized, was that they didn't promote an idea, event or product. The posters weren't actually for or about anything, unless you count as a purpose entering the numerous annual European poster competitions. The problem was, that while these designers had submitted posters that looked like posters, they just didn't feel like posters.

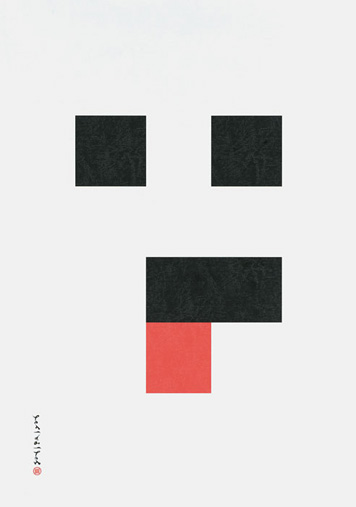

World's Minimum Dog, Ten do Ten, 2005

At the center of our debate was a set of four posters by the Japanese designer with the moniker Ten do Ten. The posters use only red and black pixels to create graphically economical images such as "World's minimum dog" and "Calligraphic self portrait." The only textual content on the posters is a proportionately small red seal and vertically oriented above it in text that mimics Japanese calligraphy the name of the artist is spelt out. Could we evaluate Ten do Ten's submissions as posters, or would we do better to acknowledge they were representative of a separate species—artworks in the shape of posters?

The fact that previously he was a non-guitar playing guitarist in the conceptual art band Delaware, and that he describes himself as the "Japanese pixel designer who designs only sexy pixel," might suggest the nature of Ten do Ten's relationship to graphic design's conventions, and to the entry rules for a poster competition.

According to Chaumont poster competition organizer Etienne Bernard, in order to qualify for selection, a poster has to have been "published." This means, he says, "that the poster must have a commissioner and must have been shown in public space." To some this sounds straightforward, but you can see how an emerging generation of designers might think that since they had published their poster on a website (albeit their own) and that it was commissioned (albeit by themselves in one of their other identities as fashion designer, musician or store owner) then they were actually following the rules.

A similar situation came up on this side of the pond when Brand New School entered into a competition some fake band posters they had created in the process of directing a cokemusic.com commercial. The commercial shows a time-lapse sequence of hipsters putting up band posters on a wall. Brand New School decided to design the posters themselves, using only their own typefaces and hand lettering. When they attempted to enter them into the typography section of AIGA's annual design competition, the posters were rejected on the grounds that they were props and not designed for the marketplace. Brand New School creative director Jens Gelhaar related this story at a conference earlier this year. "What's wrong," he asked incredulously, "with an imaginary message, usage and audience?"

It could be that the language associated with posters is the problem. Terms like "publish," "commission" and "public space"—terms that the Chaumont festival believes to be commonly understood—are today so variously interpreted as to be unrecognizable, or at least unusable without careful explanation.

In her seminal analysis of the Cuban revolutionary poster (the essay is reproduced in Looking Closer Four), Susan Sontag offers several useful definitions. One which echoed in my mind as I looked at the crop of product-less, event-less, and message-less posters at Chaumont, and considered Brand New School's imaginary usage and audience, is this: "(What is properly called a poster implies a certain context of production and distribution which excludes work, like the pseudo-posters of Warhol, produced directly for the fine arts market.) The space within which the genuine poster is shown is not elitist, but a public—communal—space [...] the poster is a public art, which addresses an undifferentiated mass of people on behalf of something public (whether a political idea or a cultural spectacle)."

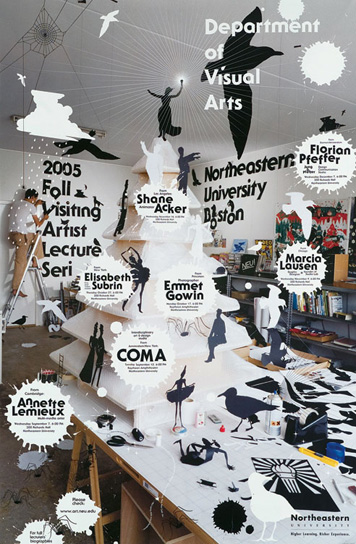

Fall Visiting Artist Lecture Series poster for Northeastern University, Harmen Liemburg, 2005

Sontag was writing in 1970 and since then the idea of a public or communal viewing space has eroded. The concept of a collective audience may well be a relic. None of the posters in the competition could reasonably be said to have communicated with mass audiences. All were directed to very particular groups: people who like Swiss Jazz festivals; people in Sydney who like Himalayan films; students in the Department of Visual Arts at Northeastern University who like lectures by visiting artists and so on. Tied to this is another anachronism: mass production and its corollary, mass distribution. Many of the posters submitted to Chaumont were reproduced in extremely small editions as silkscreen or digital prints. In some cases their reproduction in competition annuals and magazine articles may be the full extent of their distribution.

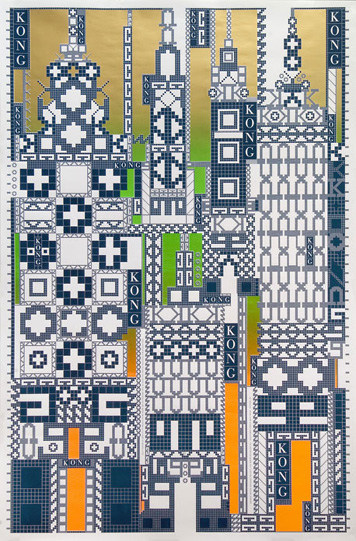

Kong, Richard Niessen, 2005

Richard Niessen's "Kong" poster is a typical example. A mosaic built up from pixellated K's, O's, N's and G's and fusing the game-scapes of Donkey Kong and Pong to create an architectural setting for King Kong, it was created as a piece of limited edition art to be displayed at the opening of a design store and gallery in Mexico City and to be sold in an edition of 20 on the designer's website.

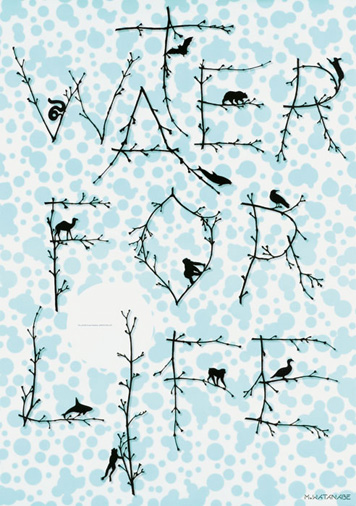

Some of them expressed worthy sentiments: "Water for Life," "Space for Green Roof Planting" or "Stop Sex with Kids" for example, but, without the legitimizing force of an institution behind them, and thereby the promise of distribution, they felt insubstantial and even disingenuous.

Water for Life, Watanabe Office, 2005

I realize that what I love about the poster, and what defines poster-ness for me, is the way it is conceptually attached to a motivating force — a product, or some event that will happen or has happened on a particular date and at a particular place. Temporal and physical fixity are integral parts of the visual language of the poster, anchors that help prevent it from floating into the ether of art. Ultimately it's the tension between those anchors and the tug of the designer's artistic ambition that produces the powerful, beautiful poster.

But the real essence of a poster, rather than an artwork, I think, is the invisible but palpable contract between a designer, the commissioning institution, organization or company that funds a poster's distribution, and the viewing public who engages with it. The designer agrees to make something to promote this product, advance this cause, project this message because he believes in it and, because of that, often makes it more beautiful than it needs to be. The client promises to produce as many copies of the poster as she can afford to and to circulate them in the most strategic ways she knows. Lastly, it is understood that if the passerby is persuaded and seduced by the poster, they will carry out whatever action it calls for. It is this unseen tripartite contract, and all the conflict it brings with it that gives the poster its urgency and reason for being. Without that tension, the poster ends at the wall.