Computer rendering by Christian Kerrigan.

Rachel Armstrong, who develops synthetic biology applications for the built environment, believes it could be possible to grow an artificial limestone reef underneath Venice using ‘metabolic materials’ — photosensitive protocells, engineered to be light averse. Her idea is to stop the city sinking into the soft mud on which its foundations are built — and to do so in a way that respects its non-human inhabitants.

Armstrong’s approach sounds like science fiction — but it’s informed by the ways living systems actually survive in hostile environments. When algae, shellfish and bacteria search for new territories and nutrients, for example, they sculpt the materials of their surroundings. Armstrong describes these as ‘tailored micro-environments’ — formed over time with the movements of the tides and currents.

Armstrong wants to move on from an engineering approach in which durable and inert materials are deployed as hard barriers between nature and human activity. This system has worked well for humans for the last couple of thousand of years — but wastefully: traditional building materials either grow more inert, or corrode away entirely, over time. On an evolutionary timescale, it’s not how resilient structures persist.

The alternative approach is to build structures in symbiosis with their living context. The designer’s new task, for Armstrong, is to ‘initiate beginnings, and mould with natural forces”. It’s not an exact science — “more like cooking, or an agricultural practice”.

Beyond Hydraulic Equilibrium

This focus on living systems would be profound change of approach; Venetians have been shaping the lagoon to meet human needs since the twelfth century. During the last 150 years, their powers amplified by oil-powered machines, Venetians have dug, channelled and built away even harder to deepen channels, expanded the port, and built refineries.

This high-entropy concept of infrastructure was embodied in Italy’s “Special Law’ for Venice, in 1973. In an effort to protect the city on a long-term basis, it prescribed ‘hydraulic equilibrium’ to protect the city from extreme floods and morphological degradation. Its main outcome has been an engineering project, called MOSE, in which huge mobile gates (whose location is shown in the picture below) are being built to isolate the lagoon from the Adriatic Sea when tides get too high.

Its critics charge that MOSE will further upset the lagoon’s hydrogeological balance and interrelated habitats that change continuously through time. Fixed engineering solutions, they say, are inappropriate for a complex environment at the interface between land and and sea. Cutting the lagoon off from sea waters may, for a time, protect the city from flooding — but at a cost: the lagoon’s living species will decline in the absence of the continuous exchange of water with the sea that is needed to oxygenate the lagoon.

The lagoon has already paid a heavy price for successive human interventions. The diversion of rivers has reduced the levels of sediments necessary to build up salt marsh beds; their area has decreased by two thirds. Channels dug to make the lagoon more accessible have accelerated erosion. Water quality has plummeted as a result of eutrophication, chemical pollution, and contamination by endocrine disrupters. Lagoon sediments have become a reservoir for other pollutants that harm bacteria, algae, and other organisms.

And now there is this:

Just when Venice thought it was full of people, with 60,000 tourists a day milling around on foot, these giant ships arrived — and in large numbers. There were more than 650 visits by such ships to the city and its lagoon last year — a number the industry hopes to double, or more, by 2020.

If cruise ships were buildings, they would not be allowed anywhere near the city; it has UNESCO status as a world heritage site. But because cruise ships move, nobody, it seems, can stop them. To add insult to injury: Although each cruise ship pays €30,000 per mooring, these fees do not go into the city’s coffers; they go to a private company, VTA, which is driving the rapid growth in cruise ship traffic.

For the Venice Port Authority — whose President, Paolo Costa, is a former mayor — cruise liners are just one harbinger of a larger ambition: to make Venice ‘the European gateway for trade flows to and from Asia’. A huge ‘Motorways of the Sea’ terminal is scheduled to open in 2013. Linked to European rail networks, it hopes to service serve up to 1,200 ferries.

The VPA website argues — absurdly, but without evident irony - that this vast expansion will make Venice a ‘green port‘. Their curious reasoning is that each container heading for Munich but unloaded in Venice — rather than a Northern European port — will ‘save’ up to 97 kg of CO2 per container.

Squeaky clean images like the one above, and all over the VPA website, are not a direct lie — but that’s because the biophysical impacts of maritime transport tend to be hidden from view. If global shipping were a country, it would be the sixth largest producer of greenhouse gas emissions — but you don’t see them; they remain out of sight, and out of mind. Also invisible are the waste flows generated in any port: sewage, grey water, grinding and blasting additives, anti-fouling coatings, paint effluent, heavy metals, oil additives, coolants, electronic waste, seals, insulation, and scrap-metals.

The citizen action group “No alle grandi navi” further charges that dredging for more and bigger ships will increase wave erosion of the lagoon and buildings. The Port Authority replies by quoting its studies of noise pollution and wave motion caused by large ships as they transit; these “prove that the delicate buildings and embankments of Venice are not at peril”.

This may also be true — but only because the lagoon as a living ecosystem is not mentioned.

Hidden Metabolism

In 2007, as work on MOSE gathered pace, the Venice Water Authority set up a new body, CORILA, to coordinate multi-disciplinary research into the lagoon’s metabolism, biodiversity, hydrodynamics, and morphology. Ecologists, biologists, chemists, engineers, geologists, and economists are working on a ‘new morphological plan’ to safeguard the lagoon as a living system.

[A charming short film — on the right hand side of the CORILA page here — describes the quest for equilibrium between man's needs and the restoration and conservation of the region's ecosystems]

Copyright National Geographic

Understanding the lagoon, as CORILA aspires to do, and finding socially acceptable ways to sustain it, are two different things. Local researchers reckon that the health of the lagoon would improve, and a properly managed aquaculture system would be viable, if ‘multiple-use conflict’ could be resolved.

But that’s a big “if”. Humans, water, and nature are profoundly interrelated in the Venice lagoon — but they are profoundly dis-connected in its governance.

While the Italian state deploys hard infrastructure to create a gated lagoon, Corila’s researchers work separately on a new morphological plan. While myriad heritage groups campaign to protect the built city from floods and tourists, artists and scientists dream up radical scenarios of their own. Native Venetian citizens, for their part, work in tourism, and dislike doing so — but hear little about these alternative projects and visions. The cruise ship industry, proclaiming that there is no alternative source of jobs and prosperity, is left to do its own, ecocidal, thing.

What’s missing is a shared vision around which all the stakeholders who are now separated from each other — municipalities, citizens, artists, mussel farmers, research institutes — could collaborate.

Bringing the lagoon as a bioregion back to life could surely be that issue.

Lagoon as Bioregion

According to Peter Berg, one of its founders, bioregionalism answers the question: ”What do we do instead?”

Rather than being protest-based, like the mainstream environmental movement (and most of Venice’s heritage groups), bioregionalism promotes an active harmony between human culture and the natural environment. It emphasises solutions that are based on local populations, knowledge, and solutions — not on global markets.

Venice as a bioregion would surely be an evocative alternative to death-by-business-as-usual — but how to proceed from here?

It’s a demanding challenge. A bioregional approach needs to connect social as well as ecological systems. It has to operate across multiple scales: spatial, temporal, and social. Researchers from multiple disciplines need to communicate with economic actors. And everyone involved must be capable of adapting as understanding evolves.

Ecological and political researchers have come up with an governance approach that meets these requirements: It’s called adaptive co-management. Adaptive co-management emphasizes the sharing of rights, responsibilities, and power between different levels and sectors of government and civil society. It emphasizes learning from carefully structured experiments — not just from books. It advocates a polycentric approach to governance, in place of the centralised, top-down, control-minded model that persists now.

All of this would be marvellous but for one problem: a huge gulf separates a governance system that makes sense to highly-motivated researchers, and one that can mobilise and engage people in the real-world.

Otherwise stated: ‘Adaptive comanagement’ does not make the heart sing.

Bioregion as Boundary Object

But a ‘boundary object’ can. Boundary objects, which have been theorised in the world of Human Computer Interaction, are, in the words of Etienne Wenger, “entities that can link communities together and allow different groups to collaborate on a common task”. They are artefacts, experiences, or ‘tangible social interfaces‘, that bring together visions, ways of knowing, and ways of collaborating.

The creation of boundary objects to represent a bioregion is a perfect task for design — and examples are starting to appear.

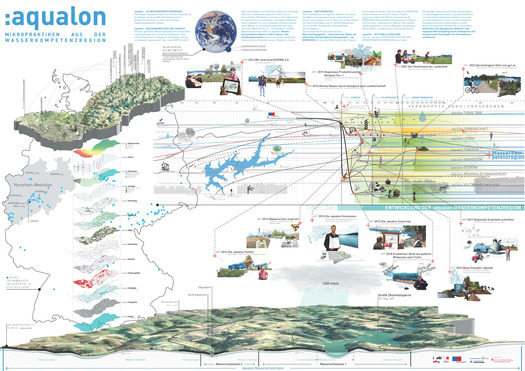

In Germany, an project called Aqualon is a model for social0-ecological water management at a regional scale. Covering a 200 square km area surrounding the Great Dhünn Dam (above) — the second largest drinking water reservoir in Germany — Aqualon brings together 30 participating municipalities in partnership with researchers from the region’s universities.

Among the latter was a team of graduate landscape and architecture students from TU Graz, and the Universaity of Wuppertal, led by Professor Klaus K Loenhart. Their contribution to Aquilon has been to develop a series of social-ecological scenarios for the watershed as a whole. These include novel forms of agriculture, sustainable forestry, land-based municipal sewage treatment, rainwater harvesting — even the settlement of beavers as ecologically valuable animals. These proposals are explained in the map below:

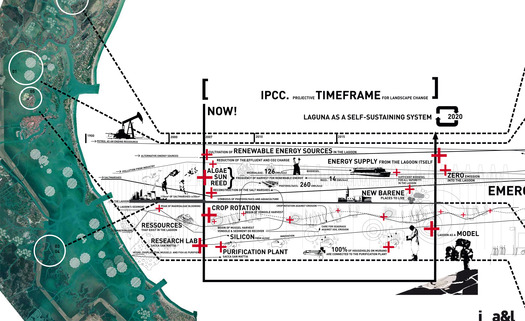

Inspired by the Aqualon experience, Loenhart last month brought a 33-strong group of architecture and landscape grad students from Europe, Chile and the US to Venice for a project called Emerging Realities. Their task was to envisage the Venice Lagoon and its archipelago as a ‘hybrid productive landscape, capable of supporting a regional community’.

With this writer as a visiting participant, Loenhart’s Emerging Realities group set up a base at Spiazzi (below). Spiazzi is a kind of Venice Hub — with the added marvellous feature that it is twinned with a green location, Spiazziverdi, elsewhere in the lagoon; our host, Michele Savorgnano, travels to Spiazziverdi by boat).

The TU Graz project has two phases: The first is an investigation and mapping of the region’s biodiversity, cultural practices, and patterns of local production. Below is an initial schematic of the various economic flows and ecosystems:

The second phase, now underway, involves looking for ways in which these different resources could be developed, and complement each other, in a future metropolitan regional system.

The guiding principle here is that natural processes, human activity, and enabling technologies, would interact ways that restore, regenerate, and reconnect. The ‘boundary object’, in this case, is the Venice Lagoon as large-scale and inter-connected working resource in which eco-systems, local food production, regionally-produced energy , would be self-sustaining.

Many questions are raised but not yet answered by the exercise so far: what final form should the ‘object’ take? where should it be located? Is a website enough, or is something tangible needed? Boundary objects for religions are icons made accessible to people in temples, and cathedrals. Is that the way to go?

We’ll revisit those questions on another occasion.