Publishing As Practice, Ulises (ed). Available through Inventory Press.

Editor’s Note: Publishing as Practice: Hardworking Goodlooking, Martine Syms/Dominica, Bidoun (Inventory Press, 2021) centers on the work of three contemporary artists/book publishers who have developed fresh ways of broaching the political in publishing.

Publishing as Practice documents a residency program at Ulises—a bookshop and exhibition space based in Philadelphia—that explores publishing as an incubator for new forms of editorial, curatorial, and artistic practice. From 2017-19 three participants, Hardworking Goodlooking (Manila, Portland, Rotterdam, NYC), Martine Syms/Dominica, Bidoun (NYC and the greater Middle East) activated Ulises as an exhibition space and public programming hub, engaging the public through workshops, discussions, and projects.

Founded in Philadelphia in 2016, Ulises is a collectively run art bookstore and exhibition space—modeled after venues such as Printed Matter and Dexter Sinister in New York—whose essayistic presentations constellate works of art, publications, and public programs around curatorial themes. The name Ulises is a tribute to the work and legacy of Ulises Carrión, a Mexican-born poet, conceptualist, and avant-garde artist who was an early pioneer and theorist of the artist’s book, and the founder of the Amsterdam based bookshop Other Books and So (1975–78). Ulises’s founding members and directors include: Nerissa Cooney, Lauren Downing, Joel Evey, Kayla Romberger, Gee Wesley, and Ricky Yanas.

Publishing As Practice was edited by Ulises and designed by Joel Evey and Davis Wise. It features a preface by David Senior, Head of Library and Archives at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and Ulises Carrión’s 1975 publishing manifesto “The New Art of Making Books,” in addition to writing and interviews with Clara Balaguer, Hardworking Goodlooking, Martine Syms, Bidoun, Lauren Downing, Gee Wesley, and Kayla Romberger, alongside excerpts and documentation from each residency. Publishing As Practice is available at Inventory Press here.

Carrión’s “The New Art of Making Books” has been re-published in full in Publishing As Practice and for the screen here.

Ulises Carrión in front of Other Books and So Archive, the second iteration of his Amsterdam-based bookstore, 1979.

WHAT A BOOK IS

A book is a sequence of spaces.

Each of these spaces is perceived at a different moment - a book is also a sequence of moments.

A book is not a case of words, nor a bag of words, nor a bearer of words.

A writer, contrary to the popular opinion, does not write books.

A writer writes texts.

The fact, that a text is contained in a book, comes only from the dimensions of such a text; or, in the case of a series of short texts (poems, for instance), from their number.

A literary (prose) text contained in a book ignores the fact that the book is an autonomous space-time sequence.

A series of more or less short texts (poems or other) distributed through a book following any

particular ordering reveals the sequential nature of the book.

It reveals it, perhaps uses it; but it does not incorporate it or assimilate it.

Written language is a sequence of signs expanding within the space; the reading of which occurs in the time.

A book is a space-time sequence.

Books existed originally as containers of (literary) texts.

But books, seen as autonomous realities, can contain any (written) language, not only literary language, or even any other system of signs.

Among languages, literary language (prose and poetry) is not the best fitted to the nature of books.

A book may be the accidental container of a text, the structure of which is irrelevant to the book: these are the books of bookshops and libraries.

A book can also exist as an autonomous and self-sufficient form, including perhaps a text that emphasizes that form, a text that is an organic part of that form: here begins the new art of making books.

In the old art the writer judges himself as being not responsible for the real book. He writes the text.

The rest is done by the servants, the artisans, the workers, the others.

In the new art writing a text is only the first link in the chain going from the writer to the reader. In the new art the writer assumes the responsibility for the whole process.

In the old art the writer writes texts.

In the new art the writer makes books.

To make a book is to actualize its ideal space-time sequence by means of the creation of a parallel sequence of signs, be it linguistic or other.

“Finissage” event at Ulises for Publishing As Practice: Hardworking Goodlooking, April 2018. Photo: Constance Mensh.

PROSE AND POETRY

In an old book all the pages are the same.

When writing the text, the writer followed only the sequential laws of language, which are not the sequential laws of books.

Words might be different on every page; but every page is, as such, identical with the preceding ones and with those that follow.

In the new art every page is different; every page is an individualized element of a structure (the book) wherein it has a particular function to fulfill.

In spoken and written language pronouns substitute for nouns, so to avoid tiresome, superfluous repetitions.

In the book, composed of various elements, of signs, such as language, what is it that plays the role of pronouns, so to avoid tiresome, superfluous repetitions?

This is a problem for the new art; the old one does not even suspect its existence.

A book of 500 pages, or of 100 pages, or even of 25, wherein all the pages are similar, is a boring book considered as a book, no matter how thrilling the content of the words of the text printed on the pages might be.

A novel, by a writer of genius or by a third-rate author, is a book where nothing happens.

There are still, and always will be, people who like reading novels. There will also always be people who like playing chess, gossiping, dancing the mambo, or eating strawberries with cream.

In comparison with novels, where nothing happens, in poetry books something happens sometimes, although very little.

A novel with no capital letters, or with different letter types, or with chemical formulae interspersed here and there etc., is still a novel, that is to say, a boring book pretending not to be such.

A book of poems contains as many words as, or more than, a novel, but it uses ultimately the real, physical space whereon these words appear, in a more intentional, more evident, deeper way.

This is so because in order to transcribe poetical language onto paper it is necessary to translate typographically the conventions proper to poetic language.

The transcription of prose needs few things: punctuation, capitals, various margins, etc.

All these conventions are original and extremely beautiful discoveries, but we don't notice them any more because we use them daily.

Transcription of poetry, a more elaborate language, uses less common signs. The mere need to create the signs fitting the transcription of poetic language, calls our attention to this very simple fact: to write a poem on paper is a different action from writing it on our mind.

Poems are songs, the poets repeat. But they don't sing them. They write them.

Poetry is to be said aloud, they repeat. But they don't say it aloud. They publish it.

The fact is, that poetry, as it occurs normally, is written and printed, not sung and spoken, poetry.

And with this, poetry has lost nothing.

On the contrary, poetry has gained something: a spatial reality that the so loudly lamented sung and spoken poetries lacked.

Installation shot of Publishing As Practice: Martine Syms/Dominica, July 2018. Photo: Constance Mensh. Courtesy of Inventory Press/Ulises.

THE SPACE

For years, many years, poets have intensively and efficiently exploited the spatial possibilities of poetry.

But only the so-called concrete or, later, visual poetry, has openly declared this.

Verses ending halfway on the page, verses having a wider or a narrower margin, verses being separated from the following one by a bigger or smaller space - all this is exploitation of space.

This is not to say that a text is poetry because it uses space in this or that way, but that using space is a characteristic of written poetry.

The space is the music of the unsung poetry

The introduction of space into poetry (or rather of poetry into space) is an enormous event of literally incalculable consequences.

One of these consequences is concrete and/or visual poetry. Its birth is not an extravagant event in the history of literature, but the natural, unavoidable development of the spatial reality gained by language since the moment writing was invented.

The poetry of the old art does use space, albeit bashfully.

This poetry establishes an inter-subjective communication.

Inter-subjective communication occurs in an abstract, ideal, impalpable space.

In the new art (of which concrete poetry is only an example) communication is still inter-subjective, but it occurs in a concrete, real, physical space - the page.

A book is a volume in the space.

It is the true ground of the communication that takes place through words - its here and now.

Concrete poetry represents an alternative to poetry.

Books, regarded as autonomous space-time sequences offer an alternative to all existent literary genres.

Space exists outside subjectivity.

If two subjects communicate in the space, then space is an element of this communication. Space modifies this communication. Space imposes its own laws on this communication.

Printed words are imprisoned in the matter of the book.

What is more meaningful: the book or the text it contains?

What was first: the chicken or the egg?

The old art assumes that printed words are printed on an ideal space.

The new art knows that books exist as objects in an exterior reality, subject to concrete conditions of perception, existence, exchange, consumption, use, etc.

The objective manifestation of language can be experienced in an isolated moment and space — the page; or in a sequence of spaces and moments - the book.

There is not and will not be new literature any more.

There will be, perhaps, new ways to communicate that will include language or will use language as a

basis.

As a medium of communication, literature will always be old literature.

A visitor perusing the Publishing As Practice: Martine Syms/Dominica pop-up shop at Ulises, July 2018. Photo: Constance Mensh.

THE LANGUAGE

Language transmits ideas, i.e. mental images.

The starting point of the transmission of mental images is always an intention: we speak to transmit a particular image.

The everyday language and the old art language have this in common: both are intentional, both want to transmit certain mental images.

In the old art the meanings of the words are the bearers of the author's intentions.

Just as the ultimate meaning of words is indefinable, so the author's intention is unfathomable.

Every intention presupposes a purpose, a utility.

Everyday language is intentional, that is, utilitarian; its function is to transmit ideas and feelings, to explain, to declare, to convince, to invoke, to accuse, etc.

Old art's language is intentional as well, i.e. utilitarian. Both languages differ from one another only in their exterior form.

New art's language is radically different from daily language. It neglects intentions and utility, and it returns to itself, it investigates itself, looking for forms, for series of forms that give birth to, couple with, unfold into, space-time sequences.

The words in a new book are not the bearers of the message, nor the mouthpieces of the soul, nor the currency of communication.

Those were already named by Hamlet, an avid reader of books: words, words, words.

The words of the new book are there not to transmit certain mental images with a certain intention.

They are there to form, together with other signs, a space-time sequence that we identify with the name 'book'.

The words in a new book might be the author's own words or someone else's words.

A writer of the new art writes very little or does not write at all.

The most beautiful and perfect book in the world is a book with only blank pages, in the same way that the most complete language is that which lies beyond all that the words of a man can say.

Every book of the new art is searching after that book of absolute whiteness, in the same way that every poem searches for silence.

Intention is the mother of rhetoric.

Words cannot avoid meaning something, but they can be divested of intentionality

A non-intentional language is an abstract language: it doesn't refer to any concrete reality.

Paradox: in order to be able to manifest itself concretely, language must first become abstract.

Abstract language means that words are not bound to any particular intention; that the word 'rose' is neither the rose that I see nor the rose that a more or less fictional character claims to see.

In the abstract language of the new art the word 'rose' is the word 'rose'. It means all the roses and it means none of them.

How to succeed in making a rose that is not my rose, nor his rose, but everybody's rose, i.e. nobody's rose?

By placing it within a sequential structure (for example a book), so that it momentarily ceases being a rose and becomes essentially an element of the structure.

Installation shot of the Bidoun Library at Ulises during Publishing As Practice: Bidoun, November 2018. Photo: Constance Mensh. Courtesy of Inventory Press/Ulises.

STRUCTURES

Every word exists as an element of a structure - a phrase, a novel, a telegram.

Or: every word is part of a text.

Nobody or nothing exists in isolation: everything is an element of a structure.

Every structure is in its turn an element of another structure.

Everything that exists is a structure.

To understand something, is to understand the structure of which it is a part and/or the elements forming the structure that that something is.

A book consists of various elements, one of which might be a text.

A text that is part of a book isn't necessarily the most essential or important part of that book.

A person may go to the bookshop to buy ten red books because this colour harmonises with the other colours in his sitting room, or for any other reason, thereby revealing the irrefutable fact, that books have a colour.

In a book of the old art words transmit the author's intention. That's why he chooses them carefully.

In a book of the new art words don't transmit any intention; they're used to form a text which is an element of a book, and it is this book, as a totality, that transmits the author's intention.

Plagiarism is the starting point of the creative activity in the new art.

Whenever the new art uses an isolated word, then it is in an absolute isolation: books of one single word.

Old art's authors have the gift for language, the talent for language, the ease for language.

For new art's authors language is an enigma, a problem; the book hints at ways to solve it.

In the old art you write 'I love you' thinking that this phrase means 'I love you'.

(But: what does 'I love you' mean?).

In the new art you write 'I love you' being aware that we don't know what this means. You write this phrase as part of a text wherein to write 'I hate you' would come to the same thing.

The important thing is, that this phrase, 'I love you' or 'I hate you', performs a certain function as a text within the structure of the book,

In the new art you don't love anybody.

The old art claims to love.

In art you can love nobody. Only in real life can you love someone.

Not that the new art lacks passions.

All of it is blood flowing out of the wound that language has inflicted on men.

And it is also the joy of being able to express something with everything, with any thing, with almost nothing, with nothing.

The old art chooses, among the literary genres and forms, that one which best fits the author's intention.

The new art uses any manifestation of language, since the author has no other intention than to test the language's ability to mean something.

The text of a book in the new art can be a novel as well as a single word, sonnets as well as jokes, love letters as well as weather reports.

In the old art, just as the author's intention is ultimately unfathomable and the sense of his words indefinable, so the understanding of the reader is unquantifiable.

In the new art the reading itself proves that the reader understands.

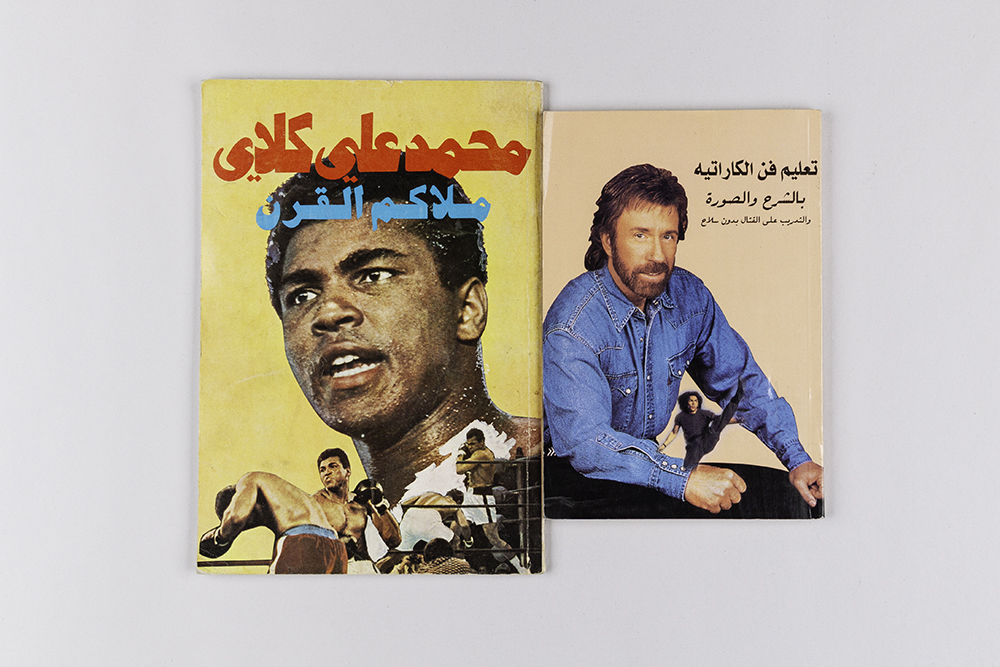

Selections from the Bidoun Library. Photo: Ricky Yanas.

THE READING

In order to read the old art, knowing the alphabet is enough.

In order to read the new art one must apprehend the book as a structure, identifying its elements and understanding their function.

One might read old art in the belief that one understands it, and be wrong.

Such a misunderstanding is impossible in the new art. You can read only if you understand.

In the old art all books are read in the same way.

In the new art every book requires a different reading.

In the old art, to read the last page takes as much time as to read the first one.

In the new art the reading rhythm changes, quickens, speeds up.

In order to understand and to appreciate a book of the old art, it is necessary to read it thoroughly.

In the new art you often do NOT need to read the whole book.

The reading may stop at the very moment you have understood the total structure of the book,

The new art makes it possible to read faster than the fast-reading methods.

There are fast-reading methods because writing methods are too slow.

To read a book, is to perceive sequentially its structure.

The old art takes no heed of reading.

The new art creates specific reading conditions.

The farthest the old art has come to, is to bring into account the readers, which is going too far.

The new art doesn't discriminate between its readers; it does not address itself to the book-addicts or try to steal its public away from TV.

In order to be able to read the new art, and to understand it, you don't need to spend five years in a Faculty of English.

In order to be appreciated, the books of the new art don't need the sentimental and/or intellectual complicity of the readers in matters of love, politics, psychology, geography, etc.

The new art appeals to the ability every man possesses for understanding and creating signs and systems of signs.

Ulises co-founder Ricky Yanas tabling at New York Art Book Fair, September 2017. Photo: Nerissa Cooney.