Photo: The Climatic Physiology of the Pig by L. E. Mount

Photo: The Climatic Physiology of the Pig by L. E. Mount

For Gunter Pauli it's the sight of electronic devices that need batteries or electric wires in order to function. For me, it's hard or paved surfaces. For Usman Haque, it's these pigs in a poke.

My obsession first. After being mesmerized by his talk at the Transition Towns event in London, I read Stephan Harding's Animate Earth, which brings the world of rocks, atmosphere, water and living things vividly to life. Harding blends science with intuition in such an extraordinary way that, before I had even finished his book, I found myself looking at tarmac surfaces and concrete runways as criminal artifacts. As so often is the case, I find I'm jumping on a pre-existing bandwagon. With the clarion cry, "Free Your Soil," de-paving groups are springing up all over the built world.

For his part Gunter Pauli cannot look with equanimity at artifacts that must be plugged in or depend on batteries to function. This is because such devices and the resource flows and power they depend on are based on "life-unfriendly engineering and energy use," and cause "unacceptable collateral damage" to the biosphere. With those conditions in place, 99% of the stuff-making work that designers currently do is rendered inappropriate. As an example of a better way to conceive and design products, Pauli told us at the Lift conference in Marseille about Humpback Heart Pacemakers. The Humpack’s 2,000-pound heart pumps the equivalent of six bath tubs of oxygenated blood through a circulatory system 4,500 times as extensive as a human’s. This is achieved at very low rates of three to four beats a minute, and electrical stimulation is achieved through a mass of blubber that shields the whale’s heart from the cold. Nano-sized ‘wires’ allow electrical signals to stimulate heart beats even through masses of non-conductive blubber. Scientists believe the findings could be the key to allowing the human heart to work without a battery-powered pacemaker. Pauli has written a new book called Nature's 100 Best together with Janine Benyus, that is packed with such examples.

This brings us neatly to Usman Haque and the Internet of Things. Janine Benyus was our keynote speaker when we discussed pervasive computing at Doors of Perception 7 in 2002. Then, as now, the European union was heavily promoting the concept of pervasive computing; these days the EU is accompanied by a critical chorus orchestrated by Rob Van Kranenburg. But at Doors 7 we wanted to know, "to what question, if any, is pervasive computing an answer?"

At the time, the one application that seemed to show promise for the sustainability agenda was environmental monitoring and control. But a fierce debate ensued concerning the efficacy of sprinkling technological devices across the planet like dust. Would this not be another futile example of man trying inappropriately to control nature with clunky and possibly toxic tools?

Seven years on, Usman and his colleagues are building a platform called Pachube that enables people to connect, tag and share real time sensor data from objects, devices, buildings and environments around the world. The aim is to facilitate interaction between remote environments, both physical and virtual. Environmental control features prominently among the myriad third party applications being developed. "Apart from enabling direct connections between any two environments," Usman explains,"it can also be used to facilitate many-to-many connections — just like a physical 'patch bay' (or telephone switchboard) Pachube enables any participating project to 'plug-in' to any other participating project in real time so that, for example, buildings, interactive installations or blogs can 'talk' and 'respond' to each other." (There's a page of possible applications here.)

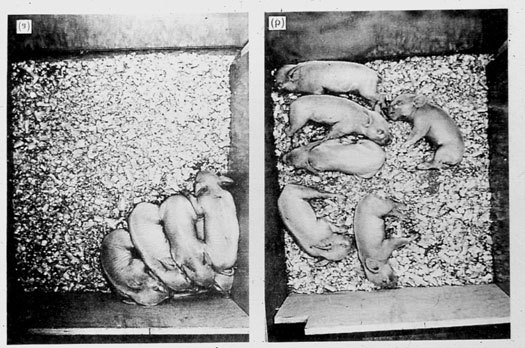

In an interview with UgoTrade Usman used the image of the pigs (top) to explain how the “software” of space (sounds, smell, light, temperature, electromagnetic fields, etc.) rather than its "hardware" (floors, walls, roof, etc.) can be shaped. In the picture, the same piglets are in the same box, but on the right hand side the temperature has been increased. This small change, remotely activated, has dramatically changed the way its inhabitants relate to each other and how they relate to their space. From this proposition, one can extrapolate ways to make existing spaces perform better in terms of energy and resource efficiency, and/or to reduce the number of new structures we need to build.

But an important condition has to be met. Connected environments of the kind that Pachube enables, and the Internet of Things as a whole, are not a step forward if they guzzle matter and energy as profligately as the internet of emails does. In Gunter Pauli's language, we should only deploy it if we can demonstrate that there will be no "collateral damage," and that's a big "if."

It's not a question of technology versus nature. As Janine Benyus framed this issue at Doors 7: "I don’t think any technology is unnatural. We are biological, and we created technology, after all. As a biologist, the question for me is not whether our technology is natural, but how well adapted it is to life on earth over the long term. Our designs are not well adapted yet."

A second big "if" for the Internet of Things concerns the degree to which digital monitoring tools may make us blind in ways that we do not intend, especially when they provide us with an artificial and misleading directness of perception. Echoing the language of Stephan Harding, Patricia de Martelaere warned, also at Doors 7, of the danger that we become "separated and alienated from direct experience of the world." For the sake of enhanced control, she cautioned, "we seem to be prepared to make our entire world artificial. Simulated and quantifiable data are presented to us as direct knowledge, whereas the intimate and subjective access we have to the world is called illusive, unreliable and valueless." De Maertelare cautioned against "wasting our lives by continuously watching images of world-processes, or processes of our own body, and desperately trying to interfere, like a man chasing his own shadow. Together with the disappearing computer, we will disappear ourselves."

This essay was originally published on Doors of Perception, July 1, 2009.