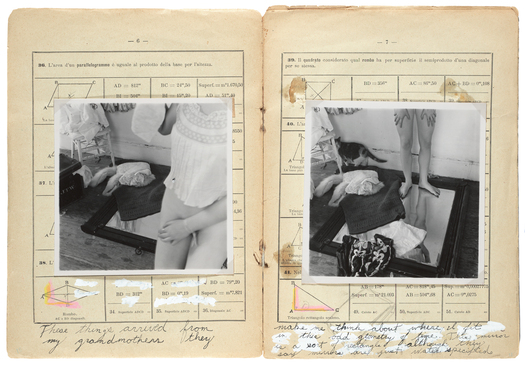

Some Disordered Interior Geometries, New York, 1980-81. Artist's book with 16 gelatin silver prints, 22.9 x 16.5 cm. Courtesy George and Betty Woodman © George and Betty Woodman

In 1977, a young American student on her junior year abroad in Rome discovered a secondhand bookshop called the Liberia Maldoror and became friends with the group of Italian artists who spent time there. They were all great admirers of surrealism. One day, she approached an owner of the bookstore (which was also an art gallery) and handed him a grey cloth box. “I’m a photographer,” she said. He opened the box. “I was both awestruck and filled with joy: standing before me was a great artist” he later recalled. The young student was the photographer Francesca Woodman.

At the Maldoror Woodman bought five tattered Italian school exercise books. A few years later, back in New York, she transformed one of them into an artist’s book that she titled Some Disordered Interior Geometries. It is featured in a retrospective of her work that is now on view at the Guggenheim Museum.

Yellowed, crumbling and torn, the exercise book is fragile-looking, something you might imagine finding at the bottom of trunk left in the corner of an attic. The book — which is more like a pamphlet — is an introduction to Euclidian geometry. Illustrated with cones, parallelograms, triangles and algebraic equations, it is the epitome of rational mathematics. But over the printed text, Woodman has tipped in a series of her own photographs. Her images are mysterious, ghostly and intimate: if the exercise book is about logical proof, Woodman’s photographs are about unanswerable questions.

On a recent Sunday afternoon at the Guggenheim, visitors gather around the waist-high vitrine in which a few pages of the notebook are displayed. They shuffle slowly. They stoop and stare. The pages are small and you have to bend over to see them, but even that doesn’t fully explain the fascination. Most of Woodman’s prints are small. The lure might come from the fact that the notebook is featured in the final room of the museum exhibition where Woodman is starting to explore new forms. Or perhaps it’s because the pages look frail and seem to demand special attention. But my suspicion is that people are drawn to Disordered Interior Geometries because of its form: they are drawn to it because it is notebook.

Woodman’s photographs, for all their purported self-confessional qualities, strike me as distanced, almost formal. She uses her body as a piece of sculpture or as a model to be arranged in poses (even when there is movement): in corners, against walls, or nakedly in juxtaposition against objects. But notebooks function in a very different way than photographic prints: they promise intimacy, revelation and raw thoughts. Nightmares scrawled and dreams recalled.

So people lean in tight, looking for clues. If they see a date, they might look even closer. Some Disordered Interior Geometries was one of her last works and was published as an artist’s book just before her suicide in January 1981.

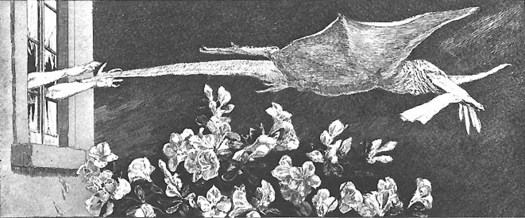

According to Giuseppe Casetti — the recipient of the grey box — an exhibition had been planned at the Malador where each artist was to be given a glove to develop as a theme. The idea was based on a series of prints made in 1881 by the proto-surrealist Max Klinger. In his series, a woman drops a glove while skating at an ice rink. This initiates a dream-like quest where the glove takes on symbolic power: it thus becomes an image of unattainable love, an object of devotion worshipped by the ocean, or something carried away in the jaws of a bizarre half-bat, half-alligator creature. Giorgio De Chirico admired Klinger (as did Max Ernst) and it’s easy to see why: Klinger’s series is unexpected and enigmatic. But Casetti’s art exhibition never took place.

Max Klinger, Ein Handschuh (A Glove), 1881

Produced several years later, Woodman’s photographs in Some Disordered Interior Geometries, are also enigmatic. A glove does appear — as do mirrors, hands, legs, fabric and chairs — and there is no narrative.

But there is handwriting. It looks like jottings. The words hold the promise of intimacy and self-revelation. The museum-goers bend in further, trying to decipher the scrawl. The words are poetic (“mirrors are just water specified”) and are written in her handwriting over patches of Tipp-Ex. As a result, the text looks labored over, as if she had difficulty choosing the right words, just like a fraught journal entry. “These things arrived from my Grandmother they make me think about where I fit in the odd geometry of time…”

But that is all we get by way of the confessional. We do see objects in the photographs that might be personal: a trunk that might be her grandmother’s, a monogrammed towel, a vintage fur scarf. But this notebook defies the very idea of a notebook. It doesn’t revel: it resists. And in so doing, it compels.

With thanks to Jennifer Blessing, curator of photography, The Guggenheim Museum