Invented as a bloodless alternative to the straightedge and strop, safety razor patents were filed as early as 1880. The device offered a close shave and a packaging boon for printers who would create razor blade wrappers. The most popular disposable blade was conceived by King Gillette, a salesman with the Baltimore Seal Company, He went into business in 1903 for himself, selling high-end double-edged blades made from thinly stamped steel. This model had not changed during much of the twentieth century, so the only distinguishing characteristic, other than price, was the brand name and wrapper design.

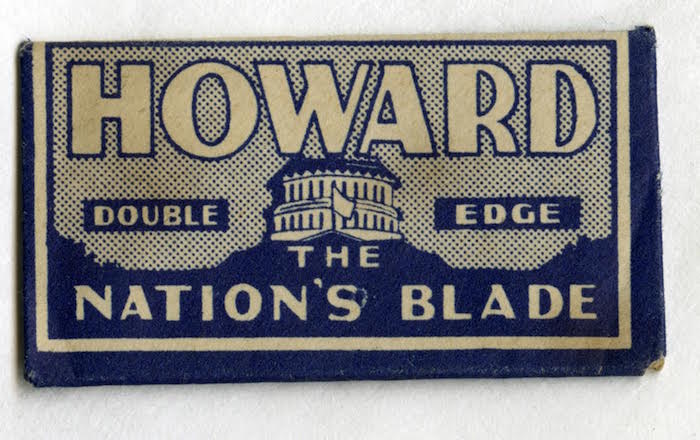

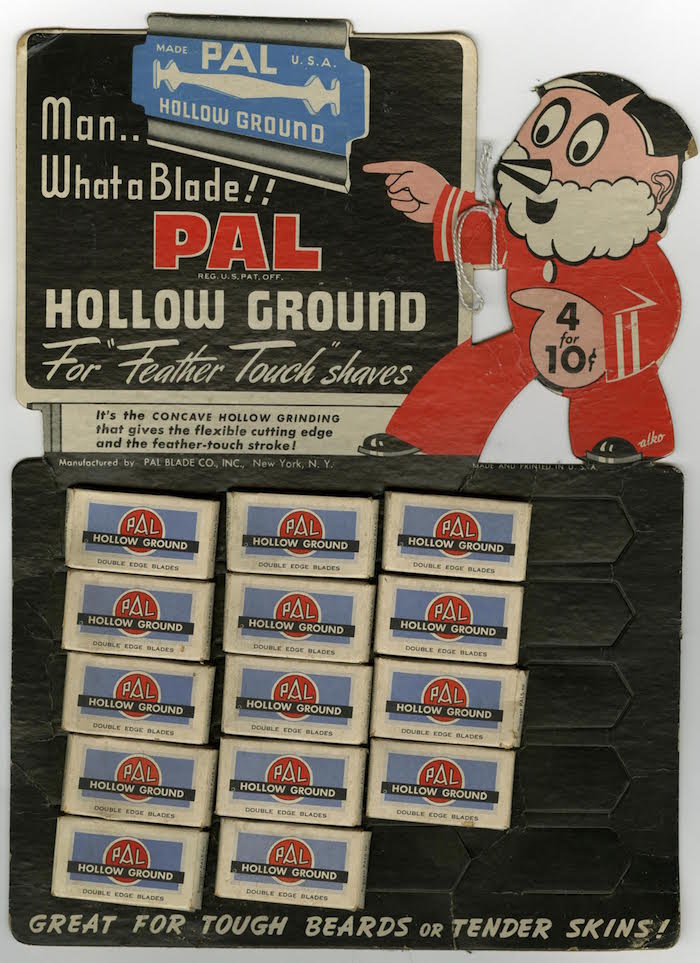

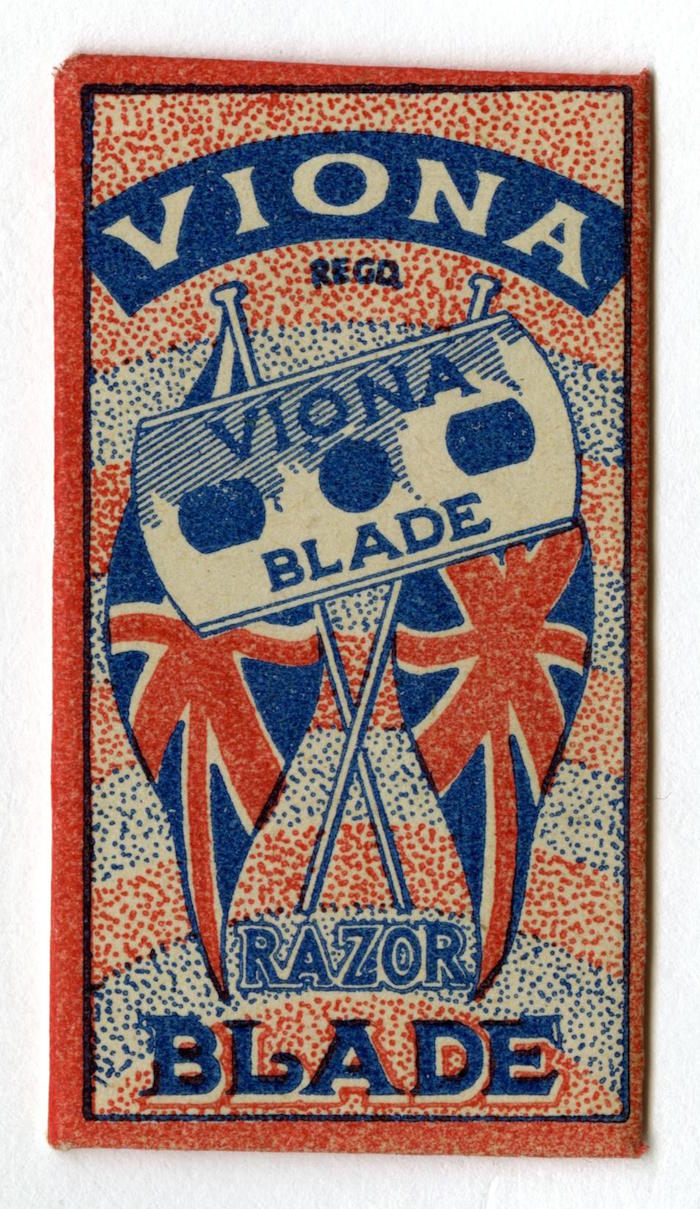

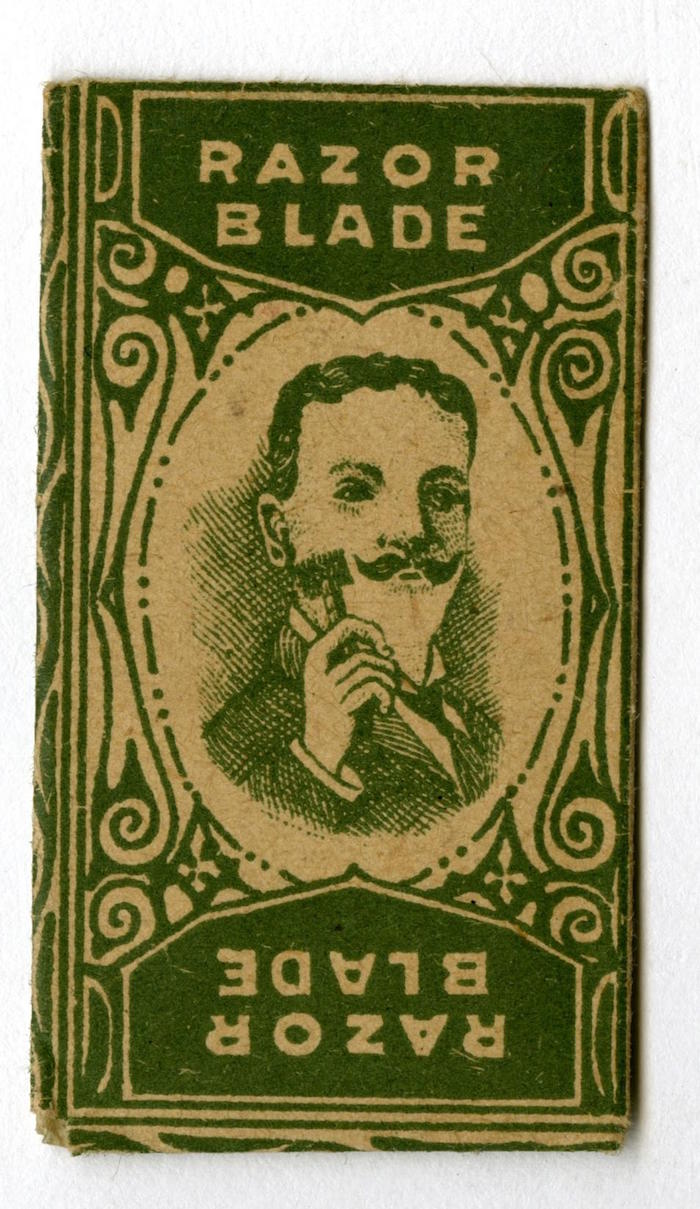

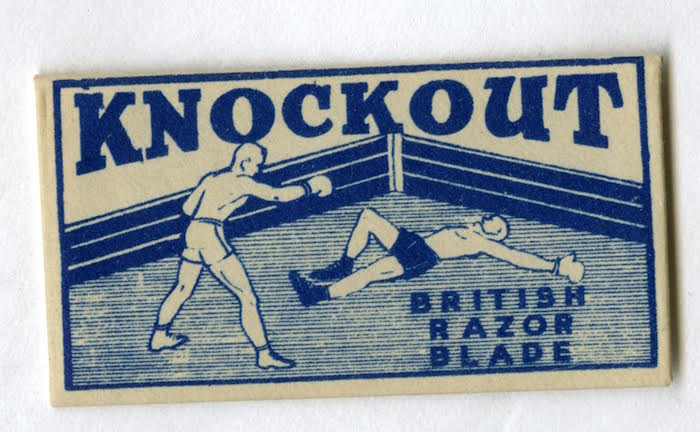

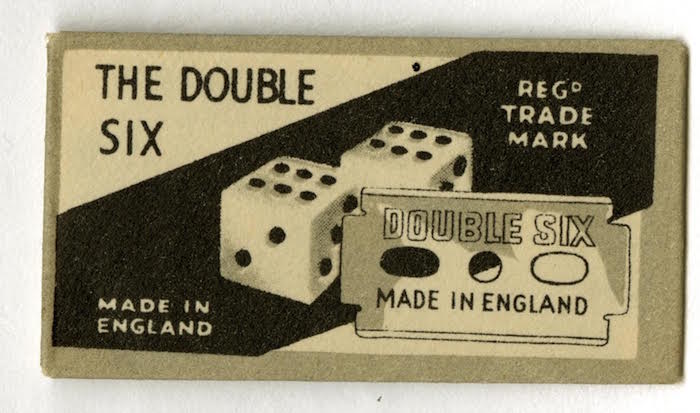

Although competing companies, including Gillette, Schick, and Wilkinson, had comparatively professional brand identities, the smaller manufacturers were impressed with pop iconography that was alternately heroic, romantic, iconic, and nonsensical, with names like Mac’s Smile, Merlin, Super Gam, Caressa, Honor, and Eclipse. Each of these wrappers (and often point of purchase displays too) was illustrated with a miniature poster image of a pulp nature. Sometimes novelty typography and other times drawings of elegant men, sensuous beauties and goofy mascots were used.

The wrappers were as ephemeral as the disposable white, blue and gold steel blades. Yet they were branded with superlatives like “superior,” “extra” and “super extra.” Although they were all made the same way, some were “flexible” and a few were called “magic.” There were so many different wrappers in circulation during the 1920s and ’30s that it's a wonder the field did not drown in competitors. But since blades were so cheap to make, single companies could produce multiple brands, with names and graphics that appealed to someone, somewhere.

Commercial artists anonymously designed blade packages. The format was prescribed, but within these limitations the image space was a tabula rasa. Bold primary color was a requisite and many wrappers were printed with metallic inks or multiple flat primary colors. Simplicity was necessary, but many were remarkably ornate and worked surprisingly well on the small, allotted area.

Blade wrappers could be delightfully naïve, with unresolved drawings or awkward type composition. But for some reason that was fine. They all conformed to an overt style that made the individual package appear larger than it was. By current standards all the specimens from this era reminded men that a good shave had benefits.