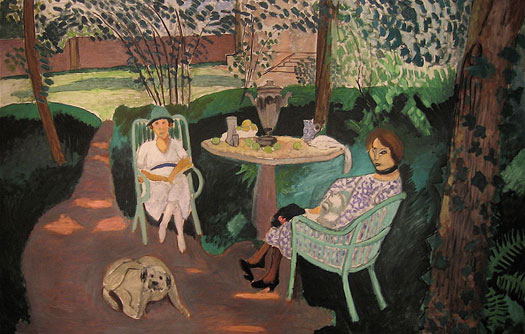

Henri Matisse, Tea, 1919. Oil on canvas, 55.25 x 83.25 in. Los Angeles County Museum of Art

“The man-made world, our environment, is potentially a work of art, all of it, every bit of it.” —David Pye, The Nature and Aesthetics of Design

In 2002, Tord Boontje, a Dutch designer known for co-authoring a collection of vases cut from recycled wine and beer bottles, produced a chandelier for the inaugural Swarovski Crystal Palace exhibition at the International Furniture Fair in Milan. Suspended from the ceiling of an enormous kohl-black space in the city's artsy warehouse district, Boontje’s Blossom mixed clusters of clear and rose-colored crystals with 240 LEDs winking on a metal branch.

Until then, Boontje's work had been largely devoted to ideas of humility and practicality. His Rough and Ready furniture collection, for instance, which was displayed at London's Tate Modern Museum in 1999, was made from simple wood, old blankets and strapping tape. Blossom, along with other floral-themed products Boontje had turned out in 2002, signified a shift for the Dutch-born designer. At the same time, the chandelier represented a departure — or rather, return — for Swarovski. One hundred years earlier, the Austrian company had perfected a technology for cutting crystal, and it had long divided its energies between science and fashion. Swarovski produced both advanced telescope lenses and costume jewelry, but since 1974 it had become popularly associated with twee animal figurines sold in mall boutiques. Under the direction of Nadja Swarovski, a direct descendant of the company’s founder, the Crystal Palace was an occasion to recapture some of the company’s earlier glamor. Eminent designers were invited to exploit all of the material’s glittering possibilities and to impress aesthetes who, by this point in a long, lavish economic boom, had thought they had seen the limits of indulgence. Swarovski, with Nadja’s blessing, went on to produce crystals studding almost every conceivable form of merchandise, from cell phones to thong underwear. It forged a democracy of luxe that allowed consumers an applied dose of sparkle for as little as $9.99 for a palm-tree-shaped hair clip to as much as $130,124 for a crystal-embedded 24-carat-gold-plated bicycle.

“The man-made world, our environment, is potentially a work of art, all of it, every bit of it.” —David Pye, The Nature and Aesthetics of Design

In 2002, Tord Boontje, a Dutch designer known for co-authoring a collection of vases cut from recycled wine and beer bottles, produced a chandelier for the inaugural Swarovski Crystal Palace exhibition at the International Furniture Fair in Milan. Suspended from the ceiling of an enormous kohl-black space in the city's artsy warehouse district, Boontje’s Blossom mixed clusters of clear and rose-colored crystals with 240 LEDs winking on a metal branch.

Until then, Boontje's work had been largely devoted to ideas of humility and practicality. His Rough and Ready furniture collection, for instance, which was displayed at London's Tate Modern Museum in 1999, was made from simple wood, old blankets and strapping tape. Blossom, along with other floral-themed products Boontje had turned out in 2002, signified a shift for the Dutch-born designer. At the same time, the chandelier represented a departure — or rather, return — for Swarovski. One hundred years earlier, the Austrian company had perfected a technology for cutting crystal, and it had long divided its energies between science and fashion. Swarovski produced both advanced telescope lenses and costume jewelry, but since 1974 it had become popularly associated with twee animal figurines sold in mall boutiques. Under the direction of Nadja Swarovski, a direct descendant of the company’s founder, the Crystal Palace was an occasion to recapture some of the company’s earlier glamor. Eminent designers were invited to exploit all of the material’s glittering possibilities and to impress aesthetes who, by this point in a long, lavish economic boom, had thought they had seen the limits of indulgence. Swarovski, with Nadja’s blessing, went on to produce crystals studding almost every conceivable form of merchandise, from cell phones to thong underwear. It forged a democracy of luxe that allowed consumers an applied dose of sparkle for as little as $9.99 for a palm-tree-shaped hair clip to as much as $130,124 for a crystal-embedded 24-carat-gold-plated bicycle.

Tord Boontje, Blossom chandelier for Swarovski, 2002.

Indeed, Blossom was emblematic of a new attitude toward beauty. After being exiled to the periphery of design, ornament, at the turn of the 21st century, was making a comeback. The 1990s had seen the rise of an industrial — even laboratory — aesthetic for the home, with stark white walls, stainless steel appliances and unforgiving concrete surfaces that seized the hearts of homeowners despite the material’s tendency to stain and crack. Classic mid-20th-century furniture pieces that had been developed with an eye to functionalist precision were de rigueur for urban lofts. Indeed, if a single item defined this modernist revival, it was Emeco’s 1006 “Navy” chair, a 1940s design originally produced for warships because, thanks to its anodized aluminum construction, it resisted rust, withstood the blasts of torpedo shells and remained buoyant after being swept overboard. By the end of the ’90s, however, the Emeco 1006 had become a style icon. Philippe Starck was commissioned to update its simple lines and polished surfaces without compromising its minimal aesthetic, and the chair could be seen in Ian Schrager hotel rooms and in episodes of “Sex and the City.”

Indeed, Blossom was emblematic of a new attitude toward beauty. After being exiled to the periphery of design, ornament, at the turn of the 21st century, was making a comeback. The 1990s had seen the rise of an industrial — even laboratory — aesthetic for the home, with stark white walls, stainless steel appliances and unforgiving concrete surfaces that seized the hearts of homeowners despite the material’s tendency to stain and crack. Classic mid-20th-century furniture pieces that had been developed with an eye to functionalist precision were de rigueur for urban lofts. Indeed, if a single item defined this modernist revival, it was Emeco’s 1006 “Navy” chair, a 1940s design originally produced for warships because, thanks to its anodized aluminum construction, it resisted rust, withstood the blasts of torpedo shells and remained buoyant after being swept overboard. By the end of the ’90s, however, the Emeco 1006 had become a style icon. Philippe Starck was commissioned to update its simple lines and polished surfaces without compromising its minimal aesthetic, and the chair could be seen in Ian Schrager hotel rooms and in episodes of “Sex and the City.”

Certainly, all was not sober on the design front of the ’90s. Whimsy defined much of the work of Starck, design’s imp of the perverse, whose 1990 Juicy Salif lemon juicer turned a simple kitchen gadget into a gleefully inappropriate and not particularly useful piece of sculpture. Meanwhile, Juicy Salif’s manufacturer, the Italian housewares company Alessi, was gearing up to produce toilet brushes resembling planters (Merdolino by Stefano Giovannoni, 1993), erotically shaped garlic presses (Antonio by Guido Venturini, 1996), and a host of other colorful designs.

And yet, such frivolity overlay a conceptual layer, requiring the viewer to pause for a moment to contemplate the relationship between, say, a flowering bathroom fixture and fertilizer. For the Dutch design collective Droog (translation: “dry”), which came to prominence in the ’90s. whimsy often dissolved into serious analyses of authorship and materiality. Such was the case with Tejo Remy’s strapped-together chest of random found drawers called You Can’t Lay Down Your Memory (1991). “It has the visual impact and provocative intent of a Dada sculpture, minus a Dadaist sense of humor,” remarked the Museum of Modern Art curators who acquired the piece for their collection. And while in the ’90s the German lighting designer Ingo Mauer displayed a wonderfully waggish tendency in such works as chandeliers made of scribbled memo-pad notes or clusters of Campari soda bottles, his obvious pleasure in experimenting with technology added a wonky layer to our enjoyment of his products. That decade’s fanciful designs for the most part bore less of what the cognitive psychologist and design critic Don Norman classifies as visceral appeal — a jolt of pure pleasure — than reflective appeal, a more subtle and contemplative genre of appreciation.

Boontje’s Blossom chandelier made a play for the visceral. It wasn’t the first design produced by a European master in the 21st century that was widely admired for its prettiness, but it was among the first to be unapologetic about its earnestness. In its winking, sparkling ways, Blossom flirted with kitsch, yet Boontje evidenced none of Starck’s knowing pleasure in that danger. In interview after interview, Boontje explained that it was the birth of his daughter Evelyn in 2000 that inspired him to turn his back on strict functionalism and embrace organic, nature-based motifs. He experimented with crystal-studded wallpaper, designed a popular light fixture of laser-cut metal leaves and flowers twisted around a bare bulb, clothed chairs in Alexander McQueen gowns, and produced sumptuous interior installations draped with lacy fabrics and furnished with benches and swings that felt like three-dimensional versions of a Fragonard painting. He quickly turned famous and much imitated and made his home in the woods of rural France.

Reclaiming beauty from irony, reclaiming beauty from kitsch — this has been a project of early-21st-century design. As many observers have noted, we are recapitulating aspects of the last century’s turn, when the floral motifs of Art Nouveau were both aided by and represented a reaction against technology’s incursions. Then as now, the designer as auteur stood as a bulwark against the prospect of increasing specialization: a William Morris or Koloman Moser put his aesthetic signature on every surface to create a meticulously fashioned world within the world, but it was the tools of specialization, the machine, that allowed such pervasive mastery. Then as now, materials generated or manipulated by new technology held a special allure, whether it was cellophane, praised, along with the National Gallery and Garbo’s salary, in Cole Porter’s 1934 song “You’re the Top,” or Tyvek, a sturdy, weatherproof DuPont product commonly used in architectural construction sites and express-mail packaging.

And yet, such frivolity overlay a conceptual layer, requiring the viewer to pause for a moment to contemplate the relationship between, say, a flowering bathroom fixture and fertilizer. For the Dutch design collective Droog (translation: “dry”), which came to prominence in the ’90s. whimsy often dissolved into serious analyses of authorship and materiality. Such was the case with Tejo Remy’s strapped-together chest of random found drawers called You Can’t Lay Down Your Memory (1991). “It has the visual impact and provocative intent of a Dada sculpture, minus a Dadaist sense of humor,” remarked the Museum of Modern Art curators who acquired the piece for their collection. And while in the ’90s the German lighting designer Ingo Mauer displayed a wonderfully waggish tendency in such works as chandeliers made of scribbled memo-pad notes or clusters of Campari soda bottles, his obvious pleasure in experimenting with technology added a wonky layer to our enjoyment of his products. That decade’s fanciful designs for the most part bore less of what the cognitive psychologist and design critic Don Norman classifies as visceral appeal — a jolt of pure pleasure — than reflective appeal, a more subtle and contemplative genre of appreciation.

Boontje’s Blossom chandelier made a play for the visceral. It wasn’t the first design produced by a European master in the 21st century that was widely admired for its prettiness, but it was among the first to be unapologetic about its earnestness. In its winking, sparkling ways, Blossom flirted with kitsch, yet Boontje evidenced none of Starck’s knowing pleasure in that danger. In interview after interview, Boontje explained that it was the birth of his daughter Evelyn in 2000 that inspired him to turn his back on strict functionalism and embrace organic, nature-based motifs. He experimented with crystal-studded wallpaper, designed a popular light fixture of laser-cut metal leaves and flowers twisted around a bare bulb, clothed chairs in Alexander McQueen gowns, and produced sumptuous interior installations draped with lacy fabrics and furnished with benches and swings that felt like three-dimensional versions of a Fragonard painting. He quickly turned famous and much imitated and made his home in the woods of rural France.

Reclaiming beauty from irony, reclaiming beauty from kitsch — this has been a project of early-21st-century design. As many observers have noted, we are recapitulating aspects of the last century’s turn, when the floral motifs of Art Nouveau were both aided by and represented a reaction against technology’s incursions. Then as now, the designer as auteur stood as a bulwark against the prospect of increasing specialization: a William Morris or Koloman Moser put his aesthetic signature on every surface to create a meticulously fashioned world within the world, but it was the tools of specialization, the machine, that allowed such pervasive mastery. Then as now, materials generated or manipulated by new technology held a special allure, whether it was cellophane, praised, along with the National Gallery and Garbo’s salary, in Cole Porter’s 1934 song “You’re the Top,” or Tyvek, a sturdy, weatherproof DuPont product commonly used in architectural construction sites and express-mail packaging.

In the Gilded Age and the turn of the 21st century alike, newly wealthy people sought ways to spend their money, and the more gratuitous the ornament applied to any surface the more it signified surplus capital. It is western culture’s nature to be bulimic, swinging between extremes of both economy and taste. We react explosively to constraint, and then sickened by glut, seek limits once again. When cataclysmic events occur, we reorder our values, and austerity takes on political or philosophical significance as it did through both World Wars, as well as during the 1970s energy crisis, and (briefly) following the events of 9/11. Recently, we passed from binging to purging again, with the collapse of the world financial markets.

But superfluity can have philosophical import, too. In 1964, the architect, industrial designer, and woodcraftsman David Pye wrote,

“Whenever humans design and make a useful thing they invariably expend a good deal of unnecessary and easily avoidable work on it which contributes nothing to its usefulness. Look, for instance, at the ceiling. It is flat. It would have been easier not to have made it flat. Its being flat does not make you any warmer or the room about you any quieter, nor yet does it make the house any cheaper; far from it. Since there is a snobbism in these things flattening a ceiling is called workmanship, or mere craftsmanship; while painting gods on it or putting knobs on it is called art or design. But all these activities: ‘workmanship,’ ‘design for appearance,’ ‘decoration,’ ‘ornament,’ ‘applied art,’ ‘embellishment,’ or what you will are part of the same pattern of behavior which all men at all times and places have followed: doing useless work on useful things. If we did not behave after this pattern our life would indeed by poor, nasty and brutish.”

Pye’s defense of flat ceilings underscores the fact that beauty, though never divorced from ideals of simplicity or essentialism, has more often been associated with the gratuitous. It’s for this reason that the art critic Dave Hickey thought he was spouting nonsense when he spontaneously declared in an early 1990s lecture room, “The issue of the nineties will be beauty!” And it accounts for the gingerly tone of the essays collected by Bill Beckley and David Shapiro in Uncontrollable Beauty: Toward a New Aesthetics (1999). In this book, critics appraising beauty in contemporary culture are mindful of the scorn long attached to the term and approach it with care. Peter Schjeldahl, for instance, posits the reason for beauty’s pariah status:

“Much resistance to admitting the reality of beauty may be motivated by disappointment with beauty’s failure to redeem the world. Experiences of beauty are sometimes attended by soaring hopes, such as that beauty may some day, or even immediately, heal humanity’s wound and rancors. It does no such thing, of course…”

Schjeldahl goes on to respond to the “is-it-trivial-or-not?” question with a deft bit of semantic judo:

“When politics is made the focus of art, beauty does not wait to be ousted from the process. Beauty deferentially withdraws, knowing its place. Beauty is not superfluous, not a luxury, but it is a necessity that waits upon the satisfaction of other necessities. It is a crowning satisfaction.”

The sudden restoration of beauty’s legitimacy in the 21st century appears to have to do with its ability to walk both sides of the street. Just as beauty is neither a luxury nor necessity but a “crowning satisfaction,” it is neither the rich person’s trophy nor the poor person’s elusive prize but a democratic gift to all. Thanks to modern manufacturing and marketing, which has built a hungry audience for it, beauty is now available at any scale or price, by way of Tiffany, Target, or Apple. But somehow, unlike the easily manufactured ornamentation at the turn of the last century that provoked the rage of aesthetes such as Adolf Loos, it has not been cheapened by its populism. (Consider, among many other examples, that the Dutch designer Hella Jongerius produced the $39.99 Jonsberg vases for IKEA practically alongside her $755 Non Temporary vase for Royal Tichelaar Makkum.)

Answering the capitalist economy’s call to create and fulfill desire in every corner of life, designers have even entered an age of superbeauty. This is the title of a section in an exhibition I recently co-curated, "The State of Things: Design and the 21st Century," currently on view at the new Design Museum Holon in Israel, designed by Ron Arad. The category is based on the premise that nothing in today’s domestic environment is too modest or obscure to be prettified: sink strainers, dish soap packages, extension cords, humidifiers, radiators, computer components, fire extinguishers. It is as if contemporary designers have vowed to make an utter sweep of domestic inventory and leave nothing unpleasing to the eye. Among the superbeautiful objects in “Only Now,” only one, Peter Arnell’s fire extinguisher for Home Depot, has a strategic (apart from sales) motive for its appeal: Arnell was concerned that people who were put off by the look of the apparatus would hide it in a drawer, obviating its purpose.

But superfluity can have philosophical import, too. In 1964, the architect, industrial designer, and woodcraftsman David Pye wrote,

“Whenever humans design and make a useful thing they invariably expend a good deal of unnecessary and easily avoidable work on it which contributes nothing to its usefulness. Look, for instance, at the ceiling. It is flat. It would have been easier not to have made it flat. Its being flat does not make you any warmer or the room about you any quieter, nor yet does it make the house any cheaper; far from it. Since there is a snobbism in these things flattening a ceiling is called workmanship, or mere craftsmanship; while painting gods on it or putting knobs on it is called art or design. But all these activities: ‘workmanship,’ ‘design for appearance,’ ‘decoration,’ ‘ornament,’ ‘applied art,’ ‘embellishment,’ or what you will are part of the same pattern of behavior which all men at all times and places have followed: doing useless work on useful things. If we did not behave after this pattern our life would indeed by poor, nasty and brutish.”

Pye’s defense of flat ceilings underscores the fact that beauty, though never divorced from ideals of simplicity or essentialism, has more often been associated with the gratuitous. It’s for this reason that the art critic Dave Hickey thought he was spouting nonsense when he spontaneously declared in an early 1990s lecture room, “The issue of the nineties will be beauty!” And it accounts for the gingerly tone of the essays collected by Bill Beckley and David Shapiro in Uncontrollable Beauty: Toward a New Aesthetics (1999). In this book, critics appraising beauty in contemporary culture are mindful of the scorn long attached to the term and approach it with care. Peter Schjeldahl, for instance, posits the reason for beauty’s pariah status:

“Much resistance to admitting the reality of beauty may be motivated by disappointment with beauty’s failure to redeem the world. Experiences of beauty are sometimes attended by soaring hopes, such as that beauty may some day, or even immediately, heal humanity’s wound and rancors. It does no such thing, of course…”

Schjeldahl goes on to respond to the “is-it-trivial-or-not?” question with a deft bit of semantic judo:

“When politics is made the focus of art, beauty does not wait to be ousted from the process. Beauty deferentially withdraws, knowing its place. Beauty is not superfluous, not a luxury, but it is a necessity that waits upon the satisfaction of other necessities. It is a crowning satisfaction.”

The sudden restoration of beauty’s legitimacy in the 21st century appears to have to do with its ability to walk both sides of the street. Just as beauty is neither a luxury nor necessity but a “crowning satisfaction,” it is neither the rich person’s trophy nor the poor person’s elusive prize but a democratic gift to all. Thanks to modern manufacturing and marketing, which has built a hungry audience for it, beauty is now available at any scale or price, by way of Tiffany, Target, or Apple. But somehow, unlike the easily manufactured ornamentation at the turn of the last century that provoked the rage of aesthetes such as Adolf Loos, it has not been cheapened by its populism. (Consider, among many other examples, that the Dutch designer Hella Jongerius produced the $39.99 Jonsberg vases for IKEA practically alongside her $755 Non Temporary vase for Royal Tichelaar Makkum.)

Answering the capitalist economy’s call to create and fulfill desire in every corner of life, designers have even entered an age of superbeauty. This is the title of a section in an exhibition I recently co-curated, "The State of Things: Design and the 21st Century," currently on view at the new Design Museum Holon in Israel, designed by Ron Arad. The category is based on the premise that nothing in today’s domestic environment is too modest or obscure to be prettified: sink strainers, dish soap packages, extension cords, humidifiers, radiators, computer components, fire extinguishers. It is as if contemporary designers have vowed to make an utter sweep of domestic inventory and leave nothing unpleasing to the eye. Among the superbeautiful objects in “Only Now,” only one, Peter Arnell’s fire extinguisher for Home Depot, has a strategic (apart from sales) motive for its appeal: Arnell was concerned that people who were put off by the look of the apparatus would hide it in a drawer, obviating its purpose.

Arnell Group, HomeHero fire extinguisher for Home Depot, 2008

Despite the prideful nature of Arnell’s fire extinguisher, it seems the goal of superbeauty is not to impress one’s friends and neighbors, unless they are expected to poke around one’s gadget drawers or under one’s desk. It is design for personal delectation. As the ability to create a modern gesamtkunstwerk has grown easier with an abundance of designers, clients, factories and consumers supporting the aesthetic enhancement of humble, resolutely functional objects, ambitions have grown, too. Like cosmetic surgery, which is driven by the promise of fulfilling one’s ideal image and is therefore a project that can never be completed, superbeauty reevaluates the world through the deceptive lens of perfectibility, lighting on formerly invisible targets (sink strainers!) and rubbing its hands as it prepares for another makeover. Its refusal to kowtow to mere public appearances in dressing the most remote corners of one’s home suggests a romantic belief that beauty nourishes us at a deep and perhaps even moral level.

Can there be an excess of beauty? Is it possible for an object to be prettier than it has to be? “Form follows function,” the principle that usability should be a guide to aesthetics has been shot down almost as frequently as it has been invoked and misattributed. Pye, for one, challenged prevailing ideas of both form — because there are far more possibilities for workable shapes in design than one might imagine — and function — because an object’s effect extends well beyond how it operates. Regarding form, he noted, “Even some paleolithic tools are considered to have been made with better workmanship than was needed to make them get results.” As for function, he wrote, “There is a difference between useless and ineffectual, no matter what the dictionary says. All the things which can give ordinary life a turn for the better are useless: affection, laughter, flowers, song, seas, mountains, play, poetry, art, and all. But they are not valueless and not ineffectual either.”

Despite the prideful nature of Arnell’s fire extinguisher, it seems the goal of superbeauty is not to impress one’s friends and neighbors, unless they are expected to poke around one’s gadget drawers or under one’s desk. It is design for personal delectation. As the ability to create a modern gesamtkunstwerk has grown easier with an abundance of designers, clients, factories and consumers supporting the aesthetic enhancement of humble, resolutely functional objects, ambitions have grown, too. Like cosmetic surgery, which is driven by the promise of fulfilling one’s ideal image and is therefore a project that can never be completed, superbeauty reevaluates the world through the deceptive lens of perfectibility, lighting on formerly invisible targets (sink strainers!) and rubbing its hands as it prepares for another makeover. Its refusal to kowtow to mere public appearances in dressing the most remote corners of one’s home suggests a romantic belief that beauty nourishes us at a deep and perhaps even moral level.

Can there be an excess of beauty? Is it possible for an object to be prettier than it has to be? “Form follows function,” the principle that usability should be a guide to aesthetics has been shot down almost as frequently as it has been invoked and misattributed. Pye, for one, challenged prevailing ideas of both form — because there are far more possibilities for workable shapes in design than one might imagine — and function — because an object’s effect extends well beyond how it operates. Regarding form, he noted, “Even some paleolithic tools are considered to have been made with better workmanship than was needed to make them get results.” As for function, he wrote, “There is a difference between useless and ineffectual, no matter what the dictionary says. All the things which can give ordinary life a turn for the better are useless: affection, laughter, flowers, song, seas, mountains, play, poetry, art, and all. But they are not valueless and not ineffectual either.”

Joris Laarman, Wire Pod power strip for Artectnica, 2008

Although the rise of superbeauty can be explained through emotional satisfaction, technological means and consumer opportunities, however, it’s not entirely clear why the rush to beauty came with such vigor almost a decade after Hickey began reintroducing the idea into art critical discourse, and long into the economic boom that made the proliferation of such beauty possible.

One explanation lies in the philosopher Arthur Danto’s musings over beauty’s distasteful associations. Writing in 1994 in defense of Matisse after the artist had been judged by the art critic Richard Dorment to be “infinitely” inferior to Picasso, Danto noted that Matisse “has sought to create a world that excludes suffering and hence the pleasure that might be taken in it.”

“His characteristic corpus has the aesthetic quality of a medieval garden — a garden of love — from whose precincts everything inconsistent with the atmosphere of beauty has been excluded. And to be in the presence of a Matisse is to look into that garden and to be in the presence of — an embodiment of — the spirit of the garden: a fragment of the earthly paradise.”

In Dorment’s view, Danto writes, “beauty is a consolation, and consolation means mitigating the bitter truth, which it is morally more admirable to admit and to face than to deny.” In other words, beauty was seen as a naïve or cowardly escape from outrage.

“And to the degree that this represents the current attitude, it is not difficult to see what has happened to beauty in contemporary art. It is not art’s business to console. If beauty is perceived as consolatory, then it is morally inconsistent with the indignation appropriate to an accusatory age.”

Although the rise of superbeauty can be explained through emotional satisfaction, technological means and consumer opportunities, however, it’s not entirely clear why the rush to beauty came with such vigor almost a decade after Hickey began reintroducing the idea into art critical discourse, and long into the economic boom that made the proliferation of such beauty possible.

One explanation lies in the philosopher Arthur Danto’s musings over beauty’s distasteful associations. Writing in 1994 in defense of Matisse after the artist had been judged by the art critic Richard Dorment to be “infinitely” inferior to Picasso, Danto noted that Matisse “has sought to create a world that excludes suffering and hence the pleasure that might be taken in it.”

“His characteristic corpus has the aesthetic quality of a medieval garden — a garden of love — from whose precincts everything inconsistent with the atmosphere of beauty has been excluded. And to be in the presence of a Matisse is to look into that garden and to be in the presence of — an embodiment of — the spirit of the garden: a fragment of the earthly paradise.”

In Dorment’s view, Danto writes, “beauty is a consolation, and consolation means mitigating the bitter truth, which it is morally more admirable to admit and to face than to deny.” In other words, beauty was seen as a naïve or cowardly escape from outrage.

“And to the degree that this represents the current attitude, it is not difficult to see what has happened to beauty in contemporary art. It is not art’s business to console. If beauty is perceived as consolatory, then it is morally inconsistent with the indignation appropriate to an accusatory age.”

If Danto is right, something happened in our culture between 1994, when his essay was published, and 2002, when the Blossom chandelier was introduced, either to make the cult of beauty no longer inconsistent with ”an accusatory age,” or to make an indignant spirit disappear altogether. The latter proposition is unlikely, given the emotionally harrowing U.S. presidential election in 2000 followed by the events of September 2001. So we may conclude that taking consolation by retreating into a Matisse-like garden — an ebullient, seemingly spontaneous though rigorously controlled blight-free zone — stopped being considered contemptible. On the contrary, it might be regarded as a justifiable alternative to confronting the overwhelming problems of our time.

Maarten Baas, Chankley Bore furniture group for Established & Sons, 2009

With the garden an acceptable place of refuge from indignation, however, it is only to be expected that Calibans are mixing in with the Ariels. Superbeauty has given rise to a counteraesthetic of extravagant ugliness, especially among a younger generation. The Dutch designer Maarten Baas may be considered the leader of this pack. He became renowned while still in graduate school at Eindhoven Academy for investigating the seductiveness of the charred surface of torched furniture. First, he burned generic pieces and then he murdered his design fathers (Mackintosh, Molino, Wright, Sottsass) by scorching reproductions of their masterpieces. Baas’s challenge to traditional beauty has evolved from there, culminating most recently in his cartoon-like Chankley Bore furniture collection for Established & Sons, which is represented in "The State of Things." The Spanish-born Nacho Carbonell, also an Eindhoven graduate who makes his home in the Netherlands, works in an arresting language of lumpy cocoon or web-like forms. But he, like Baas, is closer to the spirit of Dr. Seuss than of Salvador Dalí. Neither designer, nor many of their coevals, is applying his quirky aesthetics to political ends. Far from it. “What I want to create are objects with a fictional or fantasy element that allow you to escape everyday life," Carbonell explains on his website. This is Matisse’s garden with a different gardener holding the hedge clippers.

Adapted from "Garden of Unearthly Delights: Design and Superbeauty," in The State of Things: Design and the 21st Century, exhibition catalog published by the Design Museum Holon, 2010. Reproduced by courtesy of the Design Museum Holon, Israel.

With the garden an acceptable place of refuge from indignation, however, it is only to be expected that Calibans are mixing in with the Ariels. Superbeauty has given rise to a counteraesthetic of extravagant ugliness, especially among a younger generation. The Dutch designer Maarten Baas may be considered the leader of this pack. He became renowned while still in graduate school at Eindhoven Academy for investigating the seductiveness of the charred surface of torched furniture. First, he burned generic pieces and then he murdered his design fathers (Mackintosh, Molino, Wright, Sottsass) by scorching reproductions of their masterpieces. Baas’s challenge to traditional beauty has evolved from there, culminating most recently in his cartoon-like Chankley Bore furniture collection for Established & Sons, which is represented in "The State of Things." The Spanish-born Nacho Carbonell, also an Eindhoven graduate who makes his home in the Netherlands, works in an arresting language of lumpy cocoon or web-like forms. But he, like Baas, is closer to the spirit of Dr. Seuss than of Salvador Dalí. Neither designer, nor many of their coevals, is applying his quirky aesthetics to political ends. Far from it. “What I want to create are objects with a fictional or fantasy element that allow you to escape everyday life," Carbonell explains on his website. This is Matisse’s garden with a different gardener holding the hedge clippers.

Adapted from "Garden of Unearthly Delights: Design and Superbeauty," in The State of Things: Design and the 21st Century, exhibition catalog published by the Design Museum Holon, 2010. Reproduced by courtesy of the Design Museum Holon, Israel.