The Court of King Donald I, 2017, watercolor. Los Angeles Times.

Note: 180 pieces of Steve Brodner’s satiric art and caricature is now on view at the SVA NYC Masters Series exhibition held at SVA Chelsea Gallery, 601 West 26th St, 15th Floor from now until November 2. The following is adapted from the catalog for the show.

Caricature is Steve Brodner’s weapon of choice. Aimed with precision accuracy, his satiric barbs pierce the facades of strongmen and their stooges who deceive and delude. His work draws its strength, in part, from a keen ability to harness wit and humor. While lesser illustrator-cartoonist use clichés as substitutes for original ideas, Brodner uses common references from past and present popular culture to challenge folly and eviscerate the powerful. Take, for instance, the famous film poster for “Jaws,” showing the giant man-eating shark soaring upward like an undersea missile, just inches away from an unsuspecting, soon-to-be consumed bather. Like other symbols in Brodner’s repertoire of cultural mnemonics, this is an startling reminder of danger, evil and fear.

Brodner’s appropriation of the “Jaws” image was the cover of the Village Voice at the moment when candidate Donald J. Trump began to attack and consume his GOP rivals. Following the metaphor to a logical conclusion, it suggested that Trump, who began as a small fish in a big pond, had grown into a serious threat to all the Republicans drowning in the choppy primary sea.

“The idea behind [this] caricature,” Brodner explained at the time, “is to use Trump’s fearsome features in relation to the killer shark to bring out what is perhaps unseen under the surface of a face.” Exaggeration is only one tool for telegraphing a strong message to the largest number of people. When Brodner is on the hunt his goal is to reach a large audience far and wide. His metaphoric visual language allows him to capture attention while inflicting satiric damage.

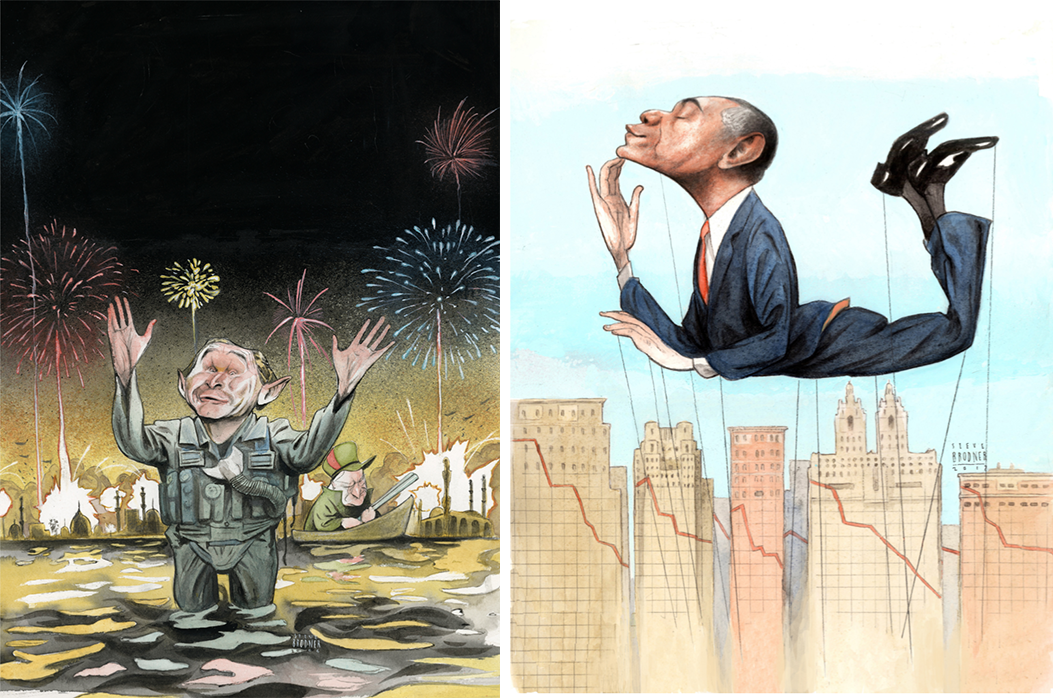

LEFT: A Heckuva Job, 2006, watercolor. Random House. RIGHT: Defying Gravity, 2012, watercolor and digital. National Journal.

Steve Brodner (b.1954) began political cartooning in 1976 for the Hudson Dispatch in Hudson County, New Jersey. Although not the most satisfying job, it provided him with an insatiable appetite for graphic political commentary. Between 1979 and 1982 he self-published the New York Illustrated News. All the while honing his skills and sharpening his blade, he worked for Harper’s, The Progressive, The New York Times, and later Esquire, The New Yorker and most major periodicals (and on video podcasts too). Brodner realized the power of his pen and that in the right circumstances, the cartoon can make opinion-altering differences, or at least affirm existing beliefs. His primary model in his early years was the pioneering mid- to late 1800s Barvarian-born American cartoonist and caricaturist Thomas Nast, whose linear cross-hatched style Brodner faithfully copied at the time.

After being so strongly influenced by Thomas Nast, Brodner transitioned out of the stylistic shadows into a decidedly original “Brodner approach,” shifting from stiff line to fluid watercolor almost overnight. When and what, I recently asked him, was the ah-ha moment that triggered the pivot? “The moment I remember was a specific assignment for the National Lampoon to illustrate an “Alice in Wonderland” parody called “Alice in Regularland” by PJ O’Rourke,” Brodner recalled. “Prior to that I had been so moved by the work of 19th century cartoonists, Nast in particular, that I absolutely believed that work of that kind, given that level of extreme care and attention would be similarly powerful in our time.” However, as Brodner was “doing this goof” on the (original Victorian) John Tenniel’s work he came to the realization that this approach was much too derivative. “What I had seen as dynamic and biting, [readers] saw as a quaint, antique curio, the very last thing I wanted.”

Also magazines were using color much more and Brodner was forced to figure out how to get there, never having painted anything before. Gradually, he made his way into watercolor, teaching himself by way of colored pencil. “Drawing with color was, for me, a gateway into watercolor. I kept on using pen and ink for black and white assignments but experimented with different line approaches, but always respecting the line much more. And, yeah, realizing at last that we were in the century of Grosz and Picasso and Ronald Searle,” he adds.

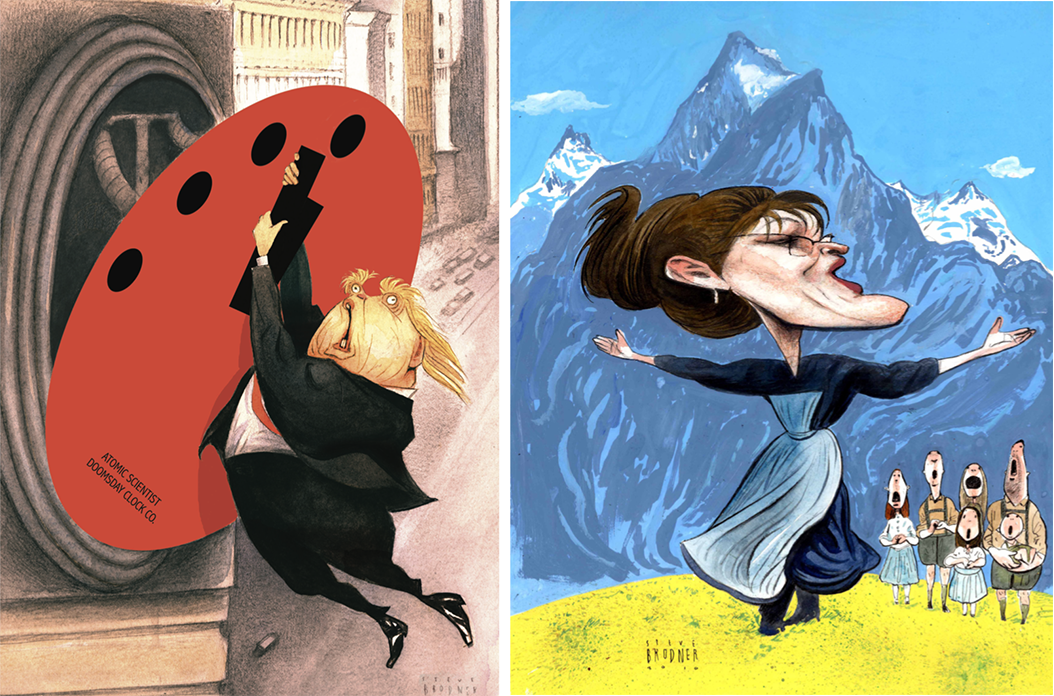

LEFT: Safety Last, 2017, watercolor and digital. The Nation. RIGHT: The Sound of Sarah, 2011, watercolor. The New Yorker.

Throughout history caricature has been the bedrock of political and social satire. Brodner is today one of a handful of illustrators who continued this legacy. I wondered how he perceives his contribution now and in the future? “Satire will carry on,” he says. “Right now it is bigger than ever. Not always for the best though. Where it used to be that to do satire you needed a publisher and an editor (who might vet the work) now the Internet is a free-for-all. There isn’t the space to allow for pauses and quiet moments that could create a moment for a quiet joke or a bit of irony that can grow into a laugh. No time for reflection. We now do one-liners and they’d better be fast and not about obscure references.” Yet despite the negatives, Brodner does not worry about his legacy. “I feel I have to do the best work I can do, tell the truth and go to bed. People tell me that it matters to them that I make pictures. I am very lucky if that is true. It’s all that matters: telling the truth. We are swimming in bullshit. I can’t think of a more important thing for anybody to do.”

Memorial, 2001, watercolor. The New Yorker.

The old canard, however, is that art does not change people’s minds, rather it reinforces existing beliefs and provides a laugh or two. “I never feel that a piece of art is in the running to change anyone’s mind,” Brodner agrees. “Watch how culture works. Conditions change making absurd ideas, suddenly possible. Could FDR have won in ’28? No. Could Reagan in ’68? No. Could you walk into a party in 1957 and tell people that they shouldn’t be smoking? No. Remember Clinton and gays-in-the-military debate? It destroyed his poll ratings in his first three months in office. Do you hear anybody now saying that we cannot have a gay president? Look now at the climate denial position. It is melting almost as fast as the Arctic. And then there’s weed! Times change. So to me, the question is: how do they actually do that? I think reality catches up with culture finally. And the culture reflects reality in many ways. During the Vietnam war the anti-war movement was boosted by, not only rock music, but also underground comics, TV comedians, comedy records, political cartoons in newspapers, political art in magazines, graphic designers, movies, posters etc. So the graphic arts is a part of mass media that cannot, in my view, be singled out as separately responsible for the movement of culture. . . But remember this, satire has no power at all if it isn’t true. Drawing a swastika on Trump’s forehead would be meaningless, until one understands how much power the racist right has derived from his various forms of support.”

Caricature can be a useful weapon or an entertainment. And the role of caricature today as Brodner sees it is significant to the extent it is published and appears before peoples’ eyes. “We have many truly great ones all making a difference. Their work forces you to consider an idea. Barry Blitt in the New Yorker, Victor Juhasz and Anita Kunz in Rolling Stone, Edel Rodrigues and Tim O’Brien in Time. And still about 50 editorial cartoonists, some employed on papers and some winging it on the net and in syndication.” He pauses while going through his mental Rollodex and is reminded of important work coming from Canada, Europe, the Americas, the Middle East. “Many risking their lives to draw. We are not making the kind of money we used to but we are making art and it is being seen. And much of it will stand with the best of all time,” he says.

Brodner has taught satiric art as part of a larger menu of approaches at SVA for some time. What, then, are the attitudes and commitments of current students towards satire and art in general as curative or aide-mémoire. “I have students who love children’s books, fantasy stories, personal memoir, humorous articles, young adult fiction. And then there are the artists who come to me with the gene to do caricature and satire,” he explains. “It is hard no matter what the topic is because of one basic reason, compression: how to jam all the necessary elements in the composition and make it super-clear and beautiful at the same time. To then put on top of that the task of representing a political point of view, without being obtuse, dilute, corny, crass, under-or-overcooked, wrong? I am amazed at what they do. I love my kids. But they must have the gene”

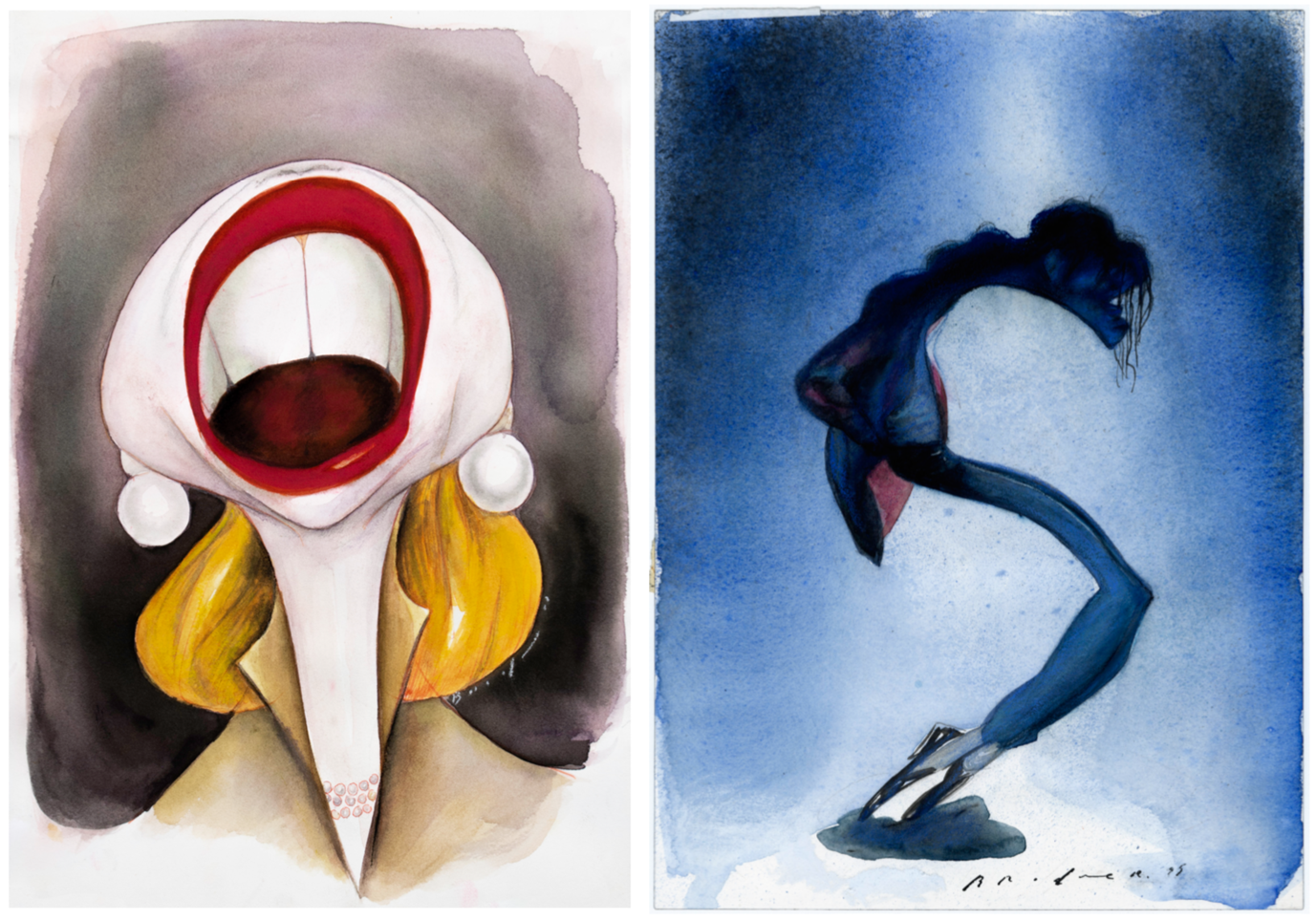

LEFT: Madonna in Evita, 1997, watercolor. Rolling Stone. RIGHT: Michael Jackson, 1995, watercolor. Entertainment Weekly.

About his own genes, he speaks excitedly of his most famous work, which in its time was the poster for the Warren Beatty film Bulworth (1998). The film wasn’t a hit but the image got a great deal of play and Brodner was very closely associated with. There were not many illustrated movie posters at that time and his stood out and won a lot of awards. “I believe it was a very good film, by the way, and one that has grown in esteem over time. However, I still wonder, how could anyone expect to make blockbuster comedy about campaign finance, produced by Fox? (Beatty to me: ‘I really don’t care. I’m a rich guy.’)” Another is “The Combover” for The Nation (2015), the drawing with the Nazi swastika etched onto his head: “It nailed Trump’s racism early on and then became a fixture on social media. It was printed out and used as a banner at rallies, projected on walls, etc. I believe the extreme nature of it is more justified every week.” And then “The Trump Ring” (2019) for The Washington Post got a great deal of response on social media and shared more than anything Brodner has ever done, soon after it ran, the Mueller Report was whitewashed “for the propaganda purposes of the Trump/Fox media machine,” he says. “This piece stands as a document, by itself, of the Russian attempt to sway an election and influence Donald Trump and his circle of goons.”

This is a critical moment in Brodner’s career. “I am in the weird position of having done everything I wanted to in this field,” he says proudly. “I have been a regular contributor at top publications, given relatively free reign to say what I have wanted. Covers, full pages, spreads of my own ideas, traveling journalist [about fifty on-location stories] cartoons, comics, TV, film, blogs, social media, political art shows with colleagues, web series. . .” He pauses then adds wistfully: “Here’s the problem: I feel I am just starting. Every day I wish I could have another crack at getting it down better. Hey, let’s try this!!! Every day new horrors emerge that need to be treated in pictures. Who can sleep?”

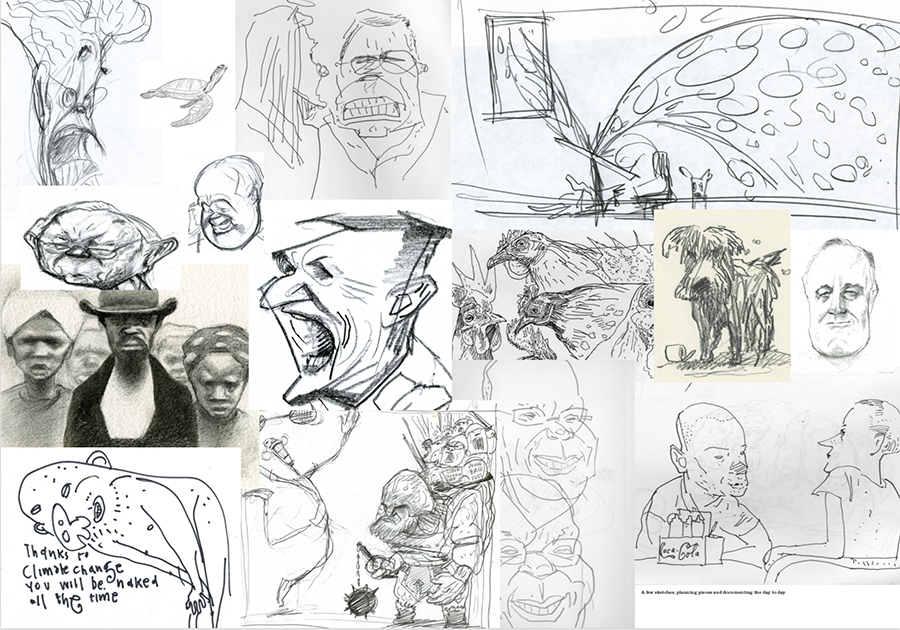

A few sketches, planning pieces and documenting the day to day.