Participants of "Reasons Not to Be Pretty: Symposium on Design, Social Change and the 'Museum,'" Bellagio, Italy

“Museums should be teaching tools where new discussions should happen, new researches should happen. How do you project different possible futures?” — Jogi Panghaal

“For too long design curators, writers and critics have fallen into the trap of style; they delight in elegance too much. We have to make a bigger effort to penetrate people’s consciousness.” — Paola Antonelli

From April 12 through April 14, 2010, 22 designers, historians, curators, educators and journalists met at Rockefeller Foundation’s Bellagio Center on Lake Como, in Italy, to discuss the museum’s role in the 21st century in relation to design for social change. Participants from a spectrum of institutions in 11 countries engaged in a far-ranging and illuminating conversation. Here, a report on this symposium sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation and organized by Winterhouse Institute.

An abstract of this report is available here. A complete list of participants is available here.

Background

Organized by William Drenttel, director of Winterhouse Institute and editorial director of the Design Observer Group, and Julie Lasky, editor of Change Observer, Reasons Not to Be Pretty: Symposium on Design, Social Change and the “Museum” grew out of the observation that scores of museums throughout the world showcase contemporary design and architecture. Such institutions remind the public of the skill that goes into making functional objects and their power to influence daily life. And yet, despite efforts to highlight design as an outgrowth of custom and a vivid reflection of community, very few museums concern themselves with social change. Instead, they are traditionally associated with high aesthetics, encapsulated in everything from Mackintosh chairs to Alessi teapots. Of the cultural institutions that have taken the lead in social change, museums of science and natural history seem to be well ahead of their design colleagues.

This is not only a missed opportunity to educate a museum’s constituencies about important contemporary themes and to promote actions with social value. It also casts a distorted perception of design’s actual and potential contribution to the world.

Designers have long been instrumental in improving housing, invigorating educational practices, engaging in environmental conservation efforts, supporting health initiatives and building local economies through such means as craft-based production. The world is filled with their breathable building skins, phosphorescent fabrics and miniature labs synthesizing “victimless leather” from living cells. And yet these inventions rarely find their way to public view.

There are enough exceptions to this rule to make a case that museums have an enormous potential to draw the public into an important dialogue about social design:

Consider, for instance, that:

> In 2007, the Smithsonian’s Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum mounted “Design for the Other 90 Percent,” innovations, in the museum’s description, that “help, rather than exploit, poorer economies; minimize environmental impact; increase social inclusion; improve healthcare at all levels; and advance the quality and accessibility of education.” The Cooper-Hewitt recently received a $600,000 Rockefeller Foundation grant for related programming and is preparing a follow-up exhibition, “Critical Mass,” on the urban design implications of global population growth, for Fall 2011.

> In 2008, the Museum of Modern Art’s ambitious “Design and the Elastic Mind” exhibition drew crowds to displays of fantastic, witty and occasionally frightening applications of technology. “Designers have the ability to grasp momentous changes in technology, science, and social mores and to convert them into objects and ideas that people can understand and use,” wrote the curator Paola Antonelli in the exhibition catalog.

> In 2009, The American Museum of Natural History hosted “Climate Change: The Threat to Life and the New Energy Future,” an example of that institution’s recent projects about dwindling natural resources, and a model of instructive social-change efforts initiated by museums outside of the art and design world.

> In 2010, the Cooper-Hewitt opened its fourth National Design Triennial, “Why Design Now?” which is devoted to projects that address human and environmental problems, from recycled materials to the greening of cities. “Design as defined here isn’t about how to make the House Beautiful more beautiful; it’s about how to keep the globe afloat and ensure that all its occupants have access to a healthy patch of it,” wrote Holland Cotter in The New York Times.

“Museums are places, people and intention.” — Galit Gaon

The 22 participants in the Winterhouse Institute symposium Reasons Not to Be Pretty were asked to consider how museums might be used more effectively as agents of social change. An allied goal was to encourage future collaborations among this international group of design professionals, all of who share a commitment to expanding the boundaries and intensifying the seriousness of contemporary design practice and education.

The conversation was divided into four themes: 1) storytelling, or creative approaches to exhibiting design and social change; 2) context, or adapting the message of social change to multiple venues and platforms; 3) form, or means of acquiring and preserving the artifacts of social change; and 4) content, or key issues and subjects for future exhibitions and platforms. These themes were refined with the assistance of Allan Chochinov, a partner of the New York-based design network Core 77, who was the symposium’s moderator.

Underpinning all four themes was the question: what is unique about the ways museums can display and archive the artifacts of social design and communicate their value to a diverse audience? What should a museum do, and be, in the 21st century?

1. Storytelling: Creative Approaches to Exhibiting Design and Social Change

“My dream exhibition is communicating issues of sanitation and drinking water. We lose 4,000 children a day to diarrhea. I see the importance of design in everything I do.” — Ashoke Chatterjee

"Every design action has consequences for someone: We need a place and a process to discuss those consequences.” — John Thackara

As the symposium’s title suggests, many exhibitors of social design aspire to raise issues to do with social change without relying on aesthetically compelling objects — or even, sometimes, on any object at all. This challenge is acute when a museum is known for the display of fine or decorative artworks that are traditionally cordoned off in a no-touch zone.

No museum object is devoid of narrative, but the importance of storytelling is especially crucial in exhibitions that engage with social change. As a first exercise, the symposium participants were therefore asked to define the characteristics of compelling presentations on design and social change and to provide examples of outstanding models from the past.

Adélia Borges, chief curator of the Brazilian Design Biennial, described a memorable exhibition prepared by 20 young people in her country’s northern state of Bahia who researched and presented design solutions in everyday life. Borges admired not just the celebration of local culture but also the transparency that turned the organizers from behind-the-scenes connoisseurs into the show’s proud subjects. “What I liked was the process of making the exhibition,” she said.

Similarly, Jeremy Myerson, director of the Helen Hamlyn Centre, a research facility at London’s Royal College of Art, endorsed museum shows in which “people are active participants in some kind of process.” He described an exhibition in Sweden in the late 1960s on disability design: “Every visitor had to climb into a wheelchair and be pushed through a dark space,” among other empathy-building activities.

Myerson also cited last year’s “In Praise of Shadows,” curated by Jane Withers, another symposium participant. Contemporary lamps designed with energy-efficient light sources were installed in darkened galleries at the Victoria and Albert Museum among 17th- through 19th-century artifacts. Visitors made their way through the murky rooms with flashlights.

For Cynthia Smith, the Cooper-Hewitt’s curator of socially responsible design, children’s museums offer valuable lessons in teaching experientially through the use of interactive media and in explaining complex ideas in a simple way. Applying those methods to design museums, which focus on objects but usually forbid touching them, has been challenging, she said. Her strategy, in exhibitions such as “Design for the Other 90 Percent,” which she organized, is using the object as an entry into the story — not as its final destination.

“People don’t go to museums in India; they are drab and uninspiring spaces,” said the Ahmedabad-based designer and educator Kiran Sethi. “How can museums come to the people?” Arguing that making puff puris and hot tea on the street is an art form, Sethi imagined the ideal social-design exhibition as one integrated into daily life. “How can designers and curators look at art from these places — pause and see with fresh eyes?” she asked. “How do we get people to look at the aesthetics and art of ordinary things?”

“I try to engage with work that has political awareness.” — Jimena Acosta

An exemplary exhibition for Paul Thompson, rector of the Royal College of Art and former director of New York’s Cooper-Hewitt and London’s Design Museum, was “Global Cities.” Curated in 2007 by urban studies scholar Ricky Burdett at the Tate Modern museum, the show used the Tate’s massive Turbine Hall to explore issues of urban development in each of 10 cities whose populations surpass 12 million.

Els van der Plas spoke about the importance of “the arts in difficult situations.” Director of the Amsterdam-based Prince Claus Fund for Culture and Development, she works to help restore the cultural infrastructure of countries afflicted by disaster. Van der Plas shared the inspiring example of the “Sapeurs” — young men in the Democratic Republic of Congo who embrace dandyism as a protest against the ravaged conditions of the slums where they live.

“My dream exhibition is called ‘A History of Violence,’” noted Paola Antonelli, senior curator in the architecture and design department of the Museum of Modern Art, referring to a show she herself would hope to organize. “The same title as the movie, and just like the movie it is an exhibition that shows what happens when good design goes bad, when it needs, uses or serves violence. It is scary to even think of curating such a show. One would have to tread such a fine line; so much could go wrong.” Among the imagined exhibits: a panopticon, Sigfried Giedion's proverbial pig’s slaughterhouse, handbags with the embossed silhouette of a kitchen knife (just in case) — and an AK47.

Niels Jarler said he wanted to “bring design into general education” and to “start to reframe historic design collections.” A curator of exhibitions for INDEX:, in Denmark, which grants generous monetary awards for “design that improves life,” Jarler was critical that too many “social design shows are not about society very much.”

“When the emphasis is on decentralization, who gets to be a designer?” asked Andrew Blauvelt. He is chief of audience engagement and communications, and curator of architecture and design, at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis (his job title reflects his unusual breadth of involvement in both the design and content of the museum’s exhibitions and graphics). Blauvelt felt there was scope for more coverage of “informal and self-organizing systems of design — the design of design” and “dematerialization of the object and its corresponding trend: fetishization of the process.”

Jamer Hunt, director of Parsons’ new MFA program in transdisciplinary design studies, compared many exhibitions focused on design and social change to bran muffins: “good for you but not pleasurable. A sense of wonder or revelation or surprise doesn’t ever seem to be part of the sensibility.” More traditional design-driven exhibitions, by contrast, “project a fantasy world about the life lived around objects, one of class and status.” The most compelling narratives, he offered, supply a strong authorial voice while disrupting the traditional structure of beginning, middle and end. Among these, Hunt suggested, are Christopher Nolan’s film Memento (2000), Julio Cortázar’s novel Hopscotch (1963) and the stories of Jorge Luis Borges.

2. Context: Adapting the Message of Social Change to Multiple Venues and Platforms

“Museums are places where you can scavenge and get inspired. They shouldn’t just be places to see and learn but also to feel and explore.” — Jane Withers

Where, ideally, should social design exhibitions be presented? Participants in Bellagio discussed the relative merits of events within and outside museums. All sorts of activities test the definition of “exhibition” but are nevertheless germane to social change. The use of technology to inhabit and make sense in different venues was also discussed.

For John Thackara, an exhibition space can be a bare 50,000-square-foot shed, or even a field. Such a shed housed his City Eco Lab at the 2008 Saint-Etienne Design Biennale. “The main function of the space was to enable conversations,” said Thackara. “We worked hard to present 50-odd sustainability projects from the region in an accessible way, but the main reason for attending was not to gawp at objects.” The event had an intentional barebones look and feel so that informal encounters and conversation would more easily blossom. “This worked a treat: Project participants talked endlessly with designers and experts and citizens throughout the two weeks.”

Kiran Sethi described an HIV-awareness campaign that was akin to street theater, mixing reality and fantasy in the effort to teach prostitutes in a red-light district in India to practice safe sex. Fearing a loss of business, the women could not be persuaded to insist that their clients wore condoms until a pair of famous actors from a very popular mythological show were hired to intervene. The actors, dressed as their screen characters, visited the district and told the women to order their clients to use condoms. The campaign was a success, Kethi said, with implications for other measures of instigating social change.

Nadine Botha, editor of the annual Design Indaba conference and trade fair in Cape Town, described the Indaba-sponsored 10 x 10 project. In this, local architects team with international practitioners to design affordable housing for the townships. The project has both a curatorial dimension in the way the work is originally conceived and exhibited and a pragmatic one in giving rise to physical shelters.

Regarding the uses of technology, Cynthia Smith said that she was creating an open network database to assist her in sharing research conducted for the upcoming Cooper-Hewitt show “Critical Mass.” “The idea is to connect people directly — organizations and individuals,” she said. “Not just institutions but also people doing work in communities. And not just people with broadband but also people who can get information through text messages.”

Ashoke Chatterjee, who directed India’s National Institute of Design for 25 years, is developing an exhibit to commemorate Gandhi’s 200-mile march in 1930 from Ahmedabad to the sea at Dandi to protest the British tax on salt. Chatterjee questioned whether it might be a good idea to turn the route itself, which passes through small town and villages, into an exhibition venue. The role of the curator would be to provide visitors with technological aids and stages to interpret it through this historical lens.

“It’s not a problem when malls act as museums but a problem when museums act as malls. We are seeing people as consumers and not as citizens.” — Adélia Borges

The visual vocabulary shared by design galleries and retail shops — their objects isolated on pedestals or grouped behind glass — gave rise to a discussion of commercial venues, such as malls.

People still go to malls even though many of their concessions are empty. Their scale and air conditioning have made them popular destinations for exercisers (a common use in the United States) or for those who want to stay cool (an important incentive for Indian visitors). Many mall-goers cannot afford to shop but treat the venue as an exhibition or performance space. This has stimulated the emergence of noncommercial mall activities. According to Chatterjee, there is a movement in Bangalore to create genuine exhibition spaces in these buildings. William Drenttel pointed out that the Mayo Clinic is planning to create a healthcare space at the Mall of America, near Minneapolis. John Thackara pointed to an irony: “Many malls are more open, more accessible and more conducive to edgy forms of expression than many security-conscious museums.”

“People in India don’t follow sequences created for them by curators; they make their own.” — Ashoke Chatterjee

“Most curators don’t like to hear that. We’re very dogmatic in how we think people should use my exhibition.” — Paul Thompson

Curators and designers usually think hard about the visitor’s progression through an exhibition space. The metaphor of the journey applies whether the exhibition space is the street, the mall or the formal gallery.

Symposium participants agreed that the experience of discovery did not depend on rigorously defined circulation routes. For one thing, visitors always establish their own hierarchies and pathways through an exhibition. For Alex Newson, a curator at the Design Museum in London, “good exhibitions use multiple narratives and points of view. I want visitors to create their own meaning.” Newson added that he often meets resistance to such impulses from within the museum.

Jamer Hunt said that in his ideal exhibition the visitor would move “out of the realm of the didactic into a place of wonder.” Rather than provide pre-cooked answers, the experience should provoke one to imagine what’s possible. “Sometimes exhibits about social change are too much about what’s been accomplished.” Chatterjee echoed Hunt’s sentiment: “In our language, the term for museum is ‘house of magic.’ That was the spontaneous response of people to buildings put up by the British to house artifacts. Is this something we might return to?”

3. Form: Acquiring and Preserving the Artifacts of Social Change

“If I think what’s valued today in a Renaissance collection of books — no one knew 200 years ago or even 100 years ago what would be valuable.” — William Drenttel

If the main emphasis in social design exhibitions is on narrative and process, should social-design artifacts be collected, and if so, how?

“If you want to be an agent of social change, don’t go down the path of collecting,” advised Paul Thompson, arguing that acquiring objects burns through resources better spent by a museum’s education department and often with no useful purpose. “Once you have captured the past, what do you do with it in the present?” he asked. “A collection is only as good as what you do with it.”

Els van der Plas had a counter-argument: “When you archive and document something, you evaluate it. The process if very important.” John Thackara concurred: “Museums are a bit like aura factories: They shape opinion about what counts.”

For Jogi Panghaal, a designer and researcher in India, Western-style institutional collecting loses relevance in a culture when so much art and design are shaped by live activity and oral tradition: “Very few people in India possess anything resembling a collectible object. But hundreds of millions of people have stories, songs, actions, wisdom and living practice, which are very inspiring, and could be shared. I don’t see why museums should confine themselves to activities that privilege such a narrow layer of culture.”

For Kiran Sethi, nonmaterial particulars are collectible in their own right. Among her candidates for preservation are rituals. “When did the hug replace the handshake, and why?” she asked. None of the eminent professionals present had an answer to that one.

“There is a difference between objects for a collection, and objects for social change,” said John Thackara. “For me, meetings and conversations between people are at the heart of social innovation. Therefore, the way I think of objects is: Does this object help bring new people together to meet? Does it stimulate meaningful conversation?”

Jamer Hunt still wanted to know: “What exactly is an object of social change? If you can call both a bench and a Karim Rashid garbage can objects of social change, then how elastic is the definition? Do we need to establish a threshold around which we say these are the kinds of projects we’re talking about?” Thackara conceded that “perhaps we should allow museums to be museums, and not overburden them with responsibilities that they are not set up to fulfill. Perhaps their role is to collect, preserve, present and reflect — and we should leave it at that.”

4. Content: Key Issues and Themes for Future Exhibitions and Platforms

In two-hour workshop sessions, participants focused in groups on storytelling and on context. Moderator Allan Chochinov asked each group to devise “recipes” for ideal social design exhibitions.

Recipes 1:

“Things are too clear, too explicit, in too many exhibitions of social change.” — Jamer Hunt

In presenting the conclusions of the first storytelling group, Jamer Hunt observed that compelling exhibitions feature two kinds of “ingredients”: elements such as light, touch, kinetics, sound, scent, scale and taste; and a nonlinear narrative structure achieved through such devices as overlapping experiences and multiple perspectives. (There was much talk at this symposium about Rashomon.)

Hunt further described a collection of techniques that defined the relationship between the exhibition and museum-goer: ideas of placemaking and process, of the museum as a “time oasis” in which visitors escape to “a different temporal field,” of subversive reframing of ideas (such as slums as a source of innovation — an idea important to Cynthia Smith’s upcoming “Critical Mass” exhibition), of touching and using, of making the visitor a co-creator of the experience, and so forth.

Ideally, Hunt went on, the effects (and affects) produced by these ingredients and techniques would restore the “surprise-wonder connection” missing from too many “pedantic and didactic” exhibitions on social change. His group’s list of effects/affects encompassed revelation, connection, resonance, disorientation, memory, conversation, strangeness, meaning, fantasy, reflection, shock and comprehension.

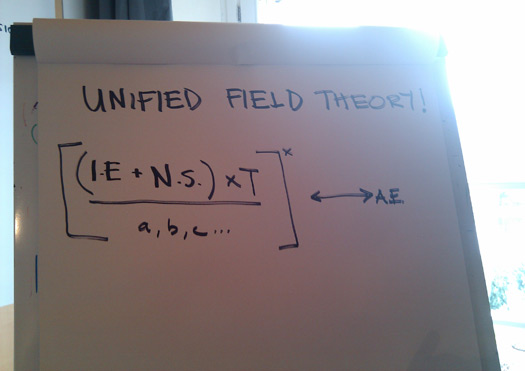

When the group put together all of these components, he said, “we realized we had not just a recipe but the recipe: a unified field theory.”

Their equation adds together interactive elements and narrative structure, multiplies it by technique and divides it by different audiences “so children may have one experience, cognoscenti another.” Repeated by a variable of x, the equation produces the combined affects and effects, and is reciprocally responsive to them.

Equation for Unified Theory of Design and Social Change exhibitions, prototype from working group, Bellagio Design Symposium

By way of illustration, Jeremy Myerson applied the formula to a show he’s preparing for the London Design Festival in September 2010. His “Future Ambulance” exhibition proposes much-needed refinements to London emergency vehicles: “People fall off the back, paramedics have the wrong kit, there are no standard design specifications.” Myerson thought that the show’s interactive elements should be “touch, feel, sound, maybe scent.” The exhibition would follow a nonlinear narrative structure, he said. And it would employ the techniques the group labeled as “process as outcome” and “please touch and use me.” Audiences for the event are expected to be medical and emergency professionals and design cognoscenti. “What we want out of it is connection, shock, comprehension,” he said.

Recipes 2:

“Sometimes exhibits about social change are too much about what’s been accomplished.” — Ashoke Chatterjee

Ashoke Chatterjee presented for the second storytelling group. “We decided we wouldn’t provide recipes, but to educate the cooks,” he said. He adumbrated four themes examining the premises of any museum-organized social-design exhibition.

First was enlarging the canvas of the symposium’s topic by recasting the phrase “design and social change” to become “design as social change.” “Every act of design is social and political,” Chatterjee argued. “To our group, the key issue is communication. Do we have any mechanisms to understand whether communication has taken place in a way we intended? What are the feedback mechanisms that can be used to test whether intentions have been fulfilled, or that there need to be midcourse corrections?” Often exhibitions are evaluated in terms of attendance, or footfall, he said. “We suggest it’s equally important to worry about mindfall. What’s happened inside the mind of those who went there, and how will we know?”

The second theme of Chatterjee’s group was appropriateness. Are museums always the best venues for supporting exhibitions of social change? To answer that question, one must first determine the exhibition’s purpose. This seemingly obvious step is often neglected in India, said Chatterjee; many museum programs, which are supported by the government, begin with a budget rather than a concept. “If you know the purpose, what are the messages that need to be exchanged in order to achieve that?” Chatterjee asked. “What media will effectively encourage that dialogue?”

The third theme echoed an interest in complexity and ambiguity that participants had expressed throughout the symposium. Chaterjee’s group advocated the use of private moments, undirected pathways and indeterminacy — “leaving the exhibition unfinished, ending with a comma rather than full stop” — to encourage participation, increase the visitor’s sense of ownership and improve the quality of narration.

Finally, Chatterjee referred to “elemental topics” and “visceral experiences” that can attract the viewer despite the constraints of censorship and the questions of authorship and authority. “Whose exhibition is it, anyway?” he asked.

Recipes 3:

“How do you let people enter a space from a more imaginative perspective?” — Andrew Blauvelt

The third symposium workshop group focused on context. Presenting for his group, Andrew Blauvelt offered seven distinct ways to approach social-design exhibitions.

In the “10x10” model, inspired by the Design Indaba’s housing initiative of that name, the museum acts as commissioner for designs for social change. The solutions are created through free, open-source contributions, and the exhibition presents not only the prototype but also “all the elements that went into it.”

The “360-degree view” model involves collaboration among a diverse group of stakeholders, both creative and financial. “People in the group are transported to the wilds of the environment and left there to bond with other human beings and natural resources,” Blauvelt explained.

The “Clearinghouse” model filters global information on a particular topic and vets it through peer review or public feedback. The information then undergoes a “dissemination phase,” where it’s distributed across any number of media platforms.

The “Why Model” asks why certain forms of innovation succeed and identifies patterns. “Multiple approaches are taken to the same question, and there is never one solution to a problem,” Blauvelt said.

The “Aspiration/Inspiration” model addresses the question: How do you encourage “the power to dream, to be comfortable with the idea of the impossible, to identify models of change?” Focusing on the museum’s role as a social and cultural watering hole, this model also seeks to balance the desire for leadership with collective engagement. “You need some kind of leadership and voice,” Blauvelt said. “Just gathering people in room won’t do it.”

The “Anti-Reduction Model” also endorses multiple approaches and perspectives. The required embrace of contradiction, paradox and tension means “you don’t need to force agreement to achieve consensus,” Blauvelt said. The displayed object becomes a force of resonance, allowing visitors “to move outward in the world to make other associations and connections.”

And finally, the “Critical Reflection” model is a kind of design clinic where participants are invited to determine problems and cures. Blauvelt described it as a “successful way to involve nonspecialists in what would otherwise be an activity for specialists.”

Conclusion

"Rather than asking what the future of design is, I would rather talk about what the future of the world is. My hope for the future of design is to create a vision that the whole world can go mad and work towards.” — Nadine Botha

As its organizers hoped, Reasons Not to Be Pretty: Symposium on Design, Social Change and the “Museum” raised more questions than it resolved. The group was inspired to continue working together to sort out what Jeremy Myerson defined as both the macro-theme (“why”) and the micro-theme (“how”) implicit in the subtitle. In pursuit of information about how museums have so far tackled social-change exhibitions, Myerson proposed that participants submit five examples of exhibitions or projects they or other institutions have organized. Change Observer is collecting and publishing these examples concurrent with this report.

Although the conversation in Bellagio was open-ended, the symposium did generate concrete ideas and areas for further discussion. The organizers have shaped these into six conclusions:

1. The Museum Can Be a Commons for Learning, Reflection and Critical Action

John Thackara remarked, “There’s a difference between what we might want a museum to be and what it is, or is likely to become. After this event I have a better understanding of what only a museum can do in the realm of social design that other institutions and contexts cannot.” The many attributes of museums spun out by the group were ultimately distilled into the idea of a commons in which collective experience is shaped and memory is created and archived. This commons is also a platform for delivering information and provocation, and a stage for learning, social connectedness and critical action. Finally, this commons is a place where people can reflect thoughtfully on the efficacy of social change efforts and how they affect their daily lives. The museum is thereby defined not only as an exhibition space but also as a civic arena; not only as a physical space but also as a platform; not only as an archive but also as a generator of historical memory; and not only as a curator of projects but also as a facilitator for understanding a project’s original context and ultimate efficacy. Beyond addressing the content of physical exhibitions, this conclusion broadly emphasizes the museum’s public and educational programs.

2. Museums Need to Move Beyond the Object

Just as design is shifting from an object-centered focus to emphasize systems and strategies, so the symposium’s discussion of social design exhibitions often extended beyond concrete displays. It was noted that participants from countries in the developing world, which are not widely known for their collecting activities, seemed less concerned with objects than with cultural practices, participatory engagement and social activism. As Adélia Borges stated, “I’m not interested in design; I’m interested in life. I see design as a tool for improving life.” Meanwhile, the starting point for participants from institutions in the developed world often began with historical collections, archival and restoration requirements, and curatorial approaches founded on exhibiting objects. On this single issue alone, the conversations at Bellagio pointed to both tensions and opportunities that need further examination. Or, to repeat Jamer Hunt’s question, “What exactly is an object of social change?”

3. Museums May Be A Place Where “Wicked” Social Problems Are Addressed

A shared space is needed in which a diverse ecology of actors and stakeholders can address such large-scale social problems as water, food systems and social justice — concerns, as John Thackara noted, “where the question is not clear, never mind the answer.” According to Thackara, “Nobody ever seems to ‘own’ a wicked problem. In days gone by that space might have been the courts, or the church, but maybe museums could play such a role in the future.” Several examples cited at Bellagio might provide new models for this shift: A planned exhibition across the Indian state of Gujarat to commemorate Gandhi's 1930 Salt March; or Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum's “Critical Mass” exhibition in 2011 and its focus on urban planning and informal communities. The challenge will be whether these presentations can move into a shared civic space (online communities, discussion and policy panels, education programs) where difficult social problems might be explored in new ways.

4. The Curator’s Role May Have to Evolve

Several participants insisted that the curator’s role in creating exhibitions and public programs is at the core of what makes a museum. This function requires that curators possess multiple areas of expertise: they are by turn historians, archivists, connoisseurs, educators and impresarios. Curators, however, do not necessarily possess skills germane to social change issues. They are not journalists reporting on design’s effectiveness in the field. Nor or they business school professors building in-depth case studies and analysis around design solutions or failures. If museums are to pursue themes of design and social change, the curator’s role should expand to foster understanding of, say, the history of slums in Latin America, or the evolution of water-moving technologies in Africa in a way that a traditional education in art or design history has not necessarily provided for.

5. Museums Can Learn from Other Institutions

The Bellagio gathering represented a mix of traditional museums and organizations that foster social change through conferences, charrettes, academic research facilities, competitions and awards programs. Non-museum programs, from INDEX: and Price Claus Awards to India’s Design for Change initiative, offered valuable lessons in how to stimulate, honor and publicize specific achievements on an international platform. Moreover, they are often generating innovation or scalable public exhibitions (international multi-city tours of INDEX: awards) and in online environments (Design for Change presentations of participants and winners).

6. Continuing the Conversation

Symposium members expressed satisfaction in engaging in a conversation that is generally neglected in their own countries. They agreed to continue sharing information, with Change Observer serving as the platform. The participants will be encouraged to post their comments to the site, which will host a comprehensive update of their recent activities in this arena by the end of 2010.

Winterhouse Institute thanks the Rockefeller Foundation and Institute of International Education for its generous support of this symposium. Thanks to Allan Chochinov and John Thackara for their assistance with drafts of this report.