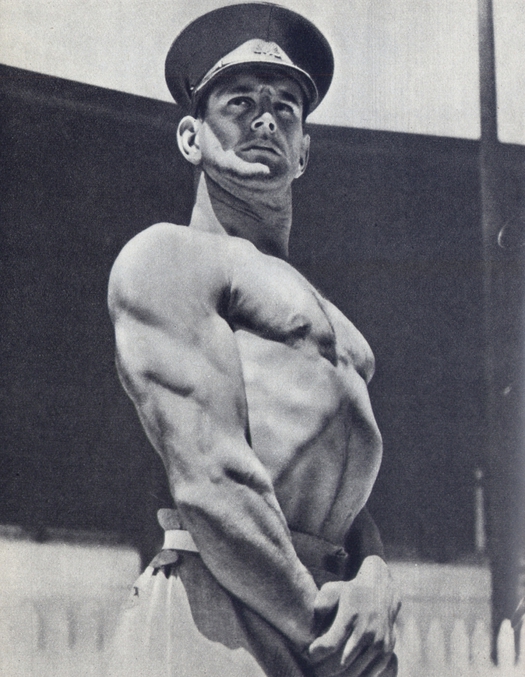

Australian serviceman (see below) from The Lilliput Annual, January-June 1940. Photograph: Central Press

Stefan Lorant, one of the founding fathers of photojournalism, was already a highly experienced editor and art director when, in July 1937, he launched Lilliput magazine in London. Lorant, born Istvn Lrnt in Hungary in 1901, had worked in silent films in Vienna and Berlin, starting as a stills photographer and rapidly progressing to director. Then he began a second career as a journalist and editor of pictorial publications such as Bilder Courier (1927-28) and Münchner Illustrierte Presse (1928-33), one of the great picture magazines, and, in Britain, Weekly Illustrated (1934).

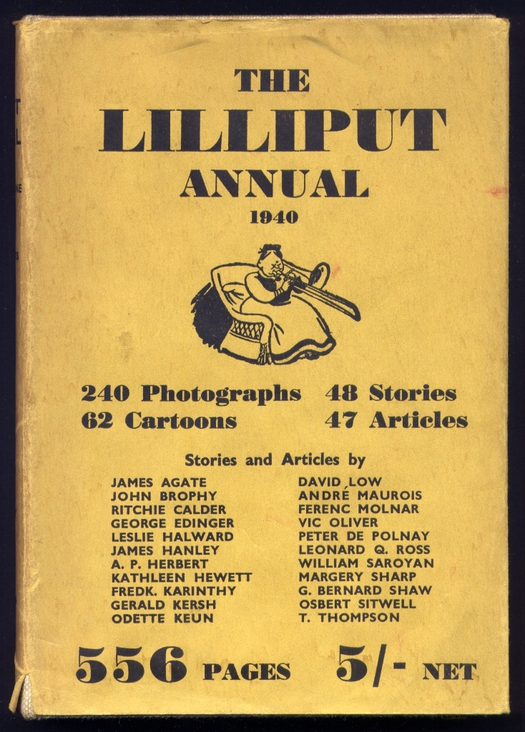

Lilliput, as its name proclaims, was Lilliputian — just 7¾ x 5½ inches. I don’t own any copies but I do have a volume of The Lilliput Annual, gathering six issues published from January to June 1940, which I found in a second-hand bookshop a few years ago. These were the last issues that Lorant was to edit. In July 1940, sick of being treated as an “enemy alien,” despite also being editor of Britain’s largest magazine, Picture Post, he quit the country to live in the United States.

The Lilliput Annual, January-June 1940, published by Pocket Publications. Editor: Stefan Lorant

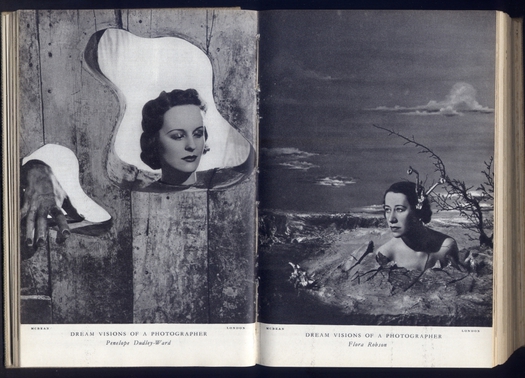

The annual is full of lively, humorous, though inevitably dated writing, but it was the photographs and the way that Lorant handled them that made it such a find. The book has several photo-essays laid out by Lorant — always eight pages — on the beauty of snow, the coming of spring, the parts of flowers, the blackout in Paris, and women of Japan (the Japanese had yet to attack Pearl Harbor). There is also a charming sequence of photographs by Angus McBean, who made surrealistic portraits of actors and comedians, though he didn’t regard himself as a serious Surrealist, according to the accompanying article, “Dream-Visions in Photographs” — “perhaps because I am not a good enough artist.” The article also notes that an officers’ club (what squeamish fellows they were) criticized McBean’s capricious portrait below of Penelope Dudley-Ward as “unhealthy and un-British.”

René Ray and Laurence Olivier. Photographs: Angus McBean

Penelope Dudley-Ward and Flora Robson. Photographs: Angus McBean

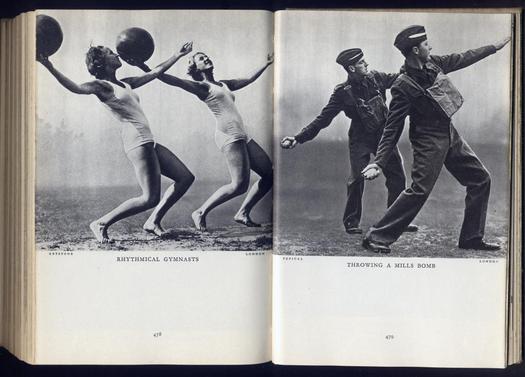

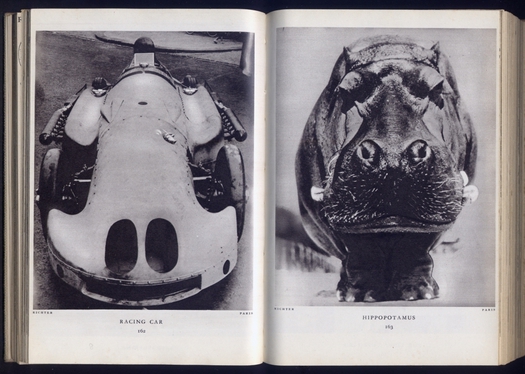

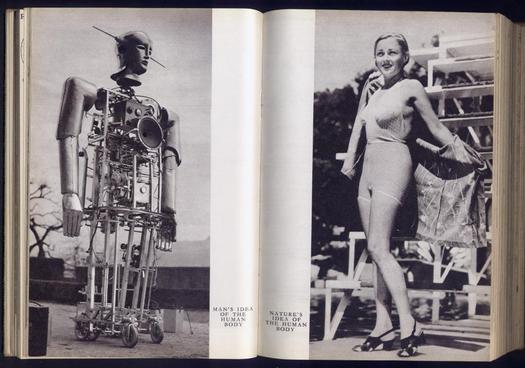

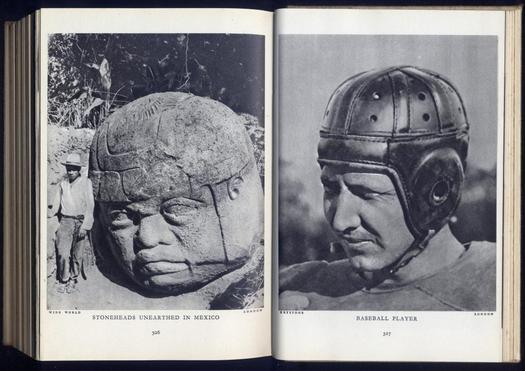

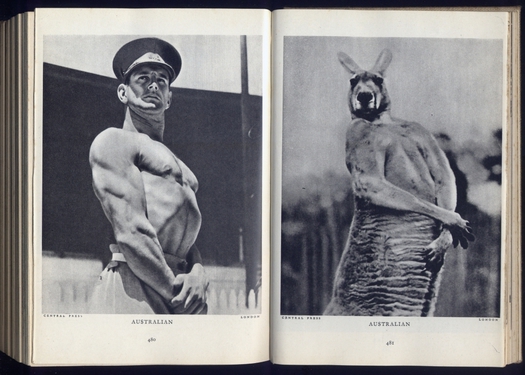

Best of all are Lorant’s famous “doubles.” He would take two pictures that resembled each other in some formal and/or thematic manner — a golfer and a road mender; an inquisitive penguin and a dignitary leaning over a rail; a barrage balloon and a rotund militia man — and place them side by side on the spread with a caption under each to reinforce the editorial purpose. These unexpected pairings can be wry, funny, bizarre, whimsical, satirical and not always kind. The war is ever-present, though still in its “phoney” phase; the pages show many morale-boosting pictures of servicemen and women readying themselves for the struggle ahead. Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and other British politicians in formal attire make largely dignified appearances, while the sinister, be-swastika’d figure of Hitler is naturally lampooned. Lilliput also lived up to its racy reputation (for the times) with many pictures tastefully celebrating the partially clad female form.

In Steven Heller’s I Heart Design, the British designer Ken Garland recalls being a devoted reader of Lilliput from the age of eight. “The monthly ritual of unveiling the array of doubles is a keenly remembered delight to this very day,” he writes, “and I was surely not the only future graphic designer or photographer to be so entranced by them.”

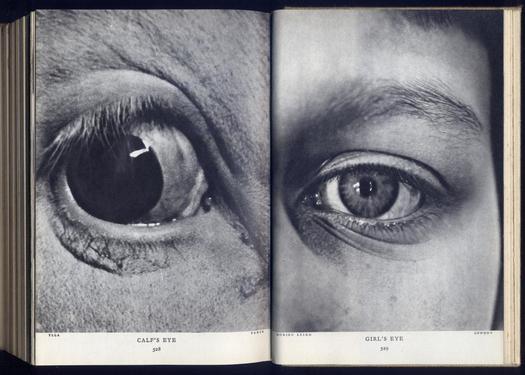

There are moments when the Surrealist method implicit in these chance encounters between images becomes unmistakable. It’s possible that Lorant knew nothing of Buñuel and Dalí’s Un Chien Andalou (1928), which opens with the slicing of a woman’s eyeball by a razor. (In reality, it was a dead calf’s eye — in the shock of the moment, the resemblance is close enough.) But it seems unlikely that a cosmopolitan filmmaker, photographer and newsman would have been unaware of this scandalous film. Either way, Lorant’s uneasy, if not cruel, juxtaposition of a calf’s eye and a girl’s eye cannot fail to recall the alarm generated by that notorious scene and its sly, audience-befuddling substitution of organs.

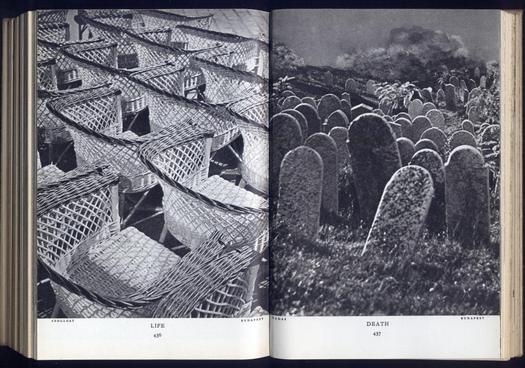

I’ll let the other doubles below, from Lorant’s final issues, speak for themselves.

Calf’s eye. Photograph: Ylla (Camilla Koffler) / Girl’s eye. Photograph: Dorien Leigh

Rhythmical gymnasts. Photograph: Keystone / Throwing a Mills bomb. Photograph: Topical

Racing car / Hippopotamus. Photographs: Richter

Man’s idea of the human body / Nature’s idea of the human body. Photographs: uncredited

Stone heads unearthed in Mexico. Photograph: Wide World / Baseball player: Photograph: Keystone

Australian / Australian. Photographs: Central Press

Life. Photograph: Kalman Szollosy / Death. Photograph: Erno Vadas