Book design by Pentagram

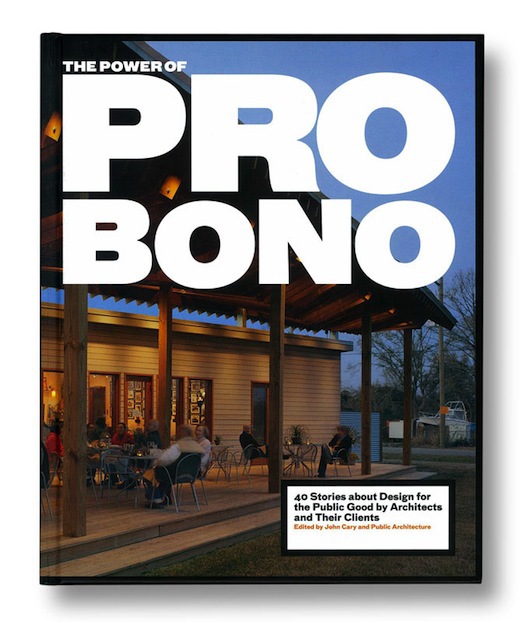

The post-Katrina influx of designers and architects to help in the reconstruction of New Orleans was in many ways an unprecedented event. With a major American city in ruins, its housing stock destroyed and its population scattered, this was a moment for fresh thinking and creative energy — and architects answered with a number of innovative designs to help citizens relocate from FEMA trailers and repopulate neighborhoods. More than 20 architects, including prominent names like David Adjaye and Shigeru Ban, joined the Make It Right Foundation’s drive to design new homes for residents of the Lower Ninth Ward, among other projects. Yet these interventions can be counted among many that architects have taken on pro bono over the past decade, as a result of a broader effort to more actively engage the profession in social change. A new book, The Power of Pro Bono: 40 Stories about Design for the Public Good by Architects and Clients (Metropolis Books, 2011), is a coffee table–quality compendium of these good works that includes, in addition to excellent photographs, side-by-side essays by architects and clients that offer a compelling back story for each project.

While it might be true that “pro bono projects remain the lesser-loved stepchildren of architectural practice,” as John Peterson, who founded the nonprofit Public Architecture in 2002 to encourage design for the public good, writes in the introduction, this book suggests that a growing number of architects are starting to think otherwise. In addition to the New Orleans houses, the survey takes in a wide range of projects for arts organizations, health centers, schools and civic buildings that all reflect not only a deep commitment by the designers but also intense collaboration between architect and client, as if these were fee-paying assignments (to underline that point, the descriptions include the estimated value of pro-bono design services).

Noteworthy projects include a large distribution center for the Greater Boston Food Bank by Chan Krieger NBBJ and a small outdoor classroom by Marpillero Pollak Architects, consisting of a 24-foot-long floating pier in Eibs Pond Park, a once derelict site on New York’s Staten Island. Architects designed affordable housing on the Amherst College campus and a school in Hillsborough, California, for children with severe physical impairments. They transformed libraries in New York’s grimmest public schools into attractive places where kids would actually want to hang out. And when two parents who had lost children to extended illness wanted to recreate hospital rooms to make patients and parents more comfortable, the large architecture firm Perkins + Will conceived a room featuring a domed glass ceiling so kids who spend a lot of time in bed can see the sky and stars.

With their thoughtful designs and focus on simple, sustainable materials, these projects improve clients’ lives without denting their patrons’ usually limited budgets. Which makes you think how wonderful the world would be if all architects devoted more of their time and skills to pro-bono assignments. That is happening, slowly, as the book notes, with more than 750 firms signing on to a Public Architecture initiative to pledge a minimum 1 percent of their time to pro-bono work. That represents more than 250,000 hours and an estimated $25 million in donated services annually. It’s a fraction, to be sure, of what it costs to build say, the world’s tallest tower or an Olympic football stadium. But it’s a start.