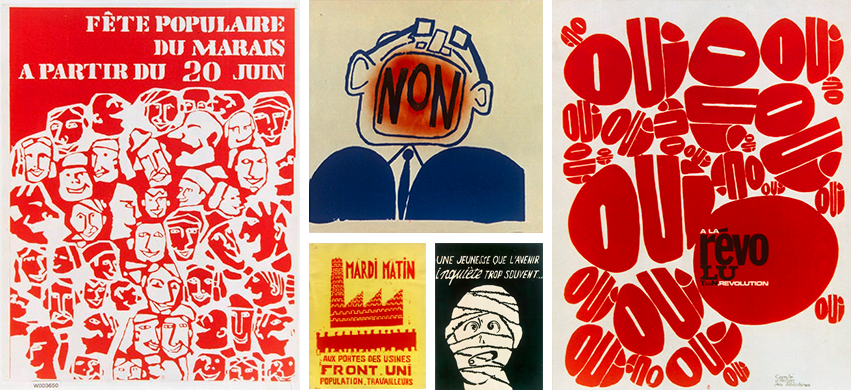

Various posters from Atelier Populaire, 1968.

If, as Marshall McLuhan suggests, the “message of any medium…is the change of scale or pace or pattern that it introduces into human affairs,” the posters created by the Atelier Populaire during the May 1968 riots in Paris may be one of the best examples of how the medium of graphic design has the capacity to help bring an entire country to its knees. As part of the riots, the Atelier Populaire, a student-run printing studio, blanketed the boulevards of Paris with activist messaging. These posters expressed a number of grievances against the state and a large number also advocated for the unison of students and blue-collar workers in an effort to fight together for societal reforms. Through their efforts, the Atelier Populaire actively worked against the spectacle of a post-war commercial society, often targeting the media and popular advertising. However, the Atelier Populaire in fact used many techniques of the mass media, specifically those of advertising, in the design of their posters. In this way, the Atelier Populaire turned the spectacle on its head, exposing the consumption ideals of modern capitalism in France and its forced separation of the classes. Though the ultimate outcome of the 1968 riots is contestable, it is nonetheless worthwhile looking at how and why the Atelier Populaire’s graphics were so effective in intensifying anti-Gaullist protests in Paris and beyond.

Before looking closely at the posters themselves, it is helpful to understand what led to their creation and the founding of the Atelier Populaire. In Beauty is in the Street, Johan Kugelberg and Philippe Vermès describe how the May 1968 riots grew out of the initial unrest of a group of students at the Université Paris Nanterre, a division of the Sorbonne located in a western Parisian suburb. Nanterre, already known for its left-wing activism, was overenrolled with students who felt confined by restrictive educational and social policies, such as a curfew and a ban against fraternizing with students of the opposite sex. On March 22, 1968, students at Nanterre staged a demonstration against the school. In a gross overreaction, several hundred of the French riot police were called in, and after stunning brutality and arrests, students at the Sorbonne across Paris staged protested to show their solidarity. Things only escalated from there. The Sorbonne was shut down on May 2 due to altercations between right and left-wing activists and the riot police used tear gas to break up the crowds. On May 6, 20,000 people marched calling for the reopening of the Sorbonne. Four days later, 30,000 protesters were barricaded on the boulevard Saint-Michel, where police had blocked off all the main streets leading out of the Latin Quarter. A battle lasted all night, with students throwing paving-stones and molotov cocktails, the police responding with batons, tear gas, and arrests. The public was shocked by the violence, and on May 13, trade unions announced a one-day general strike to show their solidarity with the students. On May 14, the Atelier Populaire printed its first poster, declaring “Usines, Universités, Union”.

usines universites union (factories, universities, union). Atelier Populaire, 1968. Silkscreen on paper. In Kugelberg, Johan, and Philippe Vermès. Beauty is in the street: a visual record of the May '68 Paris uprising. London: Four Corners Books, 2011.

The Atelier Populaire was established in the printmaking studios of the École des Beaux Arts, which had been occupied by protesting students. Above the entrance of the studio was a sign reading “ATELIER POPULAIRE OUI ATELIER BOURGEOISE NON,” effectively laying out the Atelier’s intentions. To create the posters, students used silkscreen printing, which was both a denial of specialist technologies (as per Marshall McLuhan’s critique) and playful rebuttal to capitalism’s increased “efficiency” under mechanization— thousands of posters were produced per day that were pasted in the streets under the cover of nightfall. With their bold graphics and expressive slogans, these posters critiqued the media, the state, and many, like the first, called for solidarity between workers and students.

The escalation of nation-wide labor protests that occurred after May 14 is partially a measure of the success of the Atelier’s messaging. Lasting far longer than one day, the workers’ strikes continued, and by May 23, nine million French laborers were striking, effectively shutting down the country. Charles de Gaulle, fled to a military base in Germany and expected a coup by May 29. Miraculously, however, agreements between all parties were reached. The Sorbonne reopened, the government made several minor, but evidently consenting, changes in labor policy, and things returned mostly to normal by the beginning of the summer. On June 17, the French police raided the printmaking studios of the École des Beaux Arts and the Atelier Populaire was effectively dismantled.

Though short-lived, the Atelier Populaire was able to quickly spread its anti-Gaullist message to French crowds using mere sheets of printed paper. If the modern spectacle is a self-portrait of power, as claimed by Guy Debord in his 1967 work The Society of the Spectacle, then the Atelier Populaire transformed the spectacle into their own self-portrait with their striking graphics and clever messaging. Using advertising methods to critique existing forms of media and its alliance with the state, the Atelier was able to effectively join factory workers and students in solidarity against the ruling class. Ultimately, this new union would promote education about the negative effects of modern capitalism and, theoretically, give rise to a new form of proletarianism.

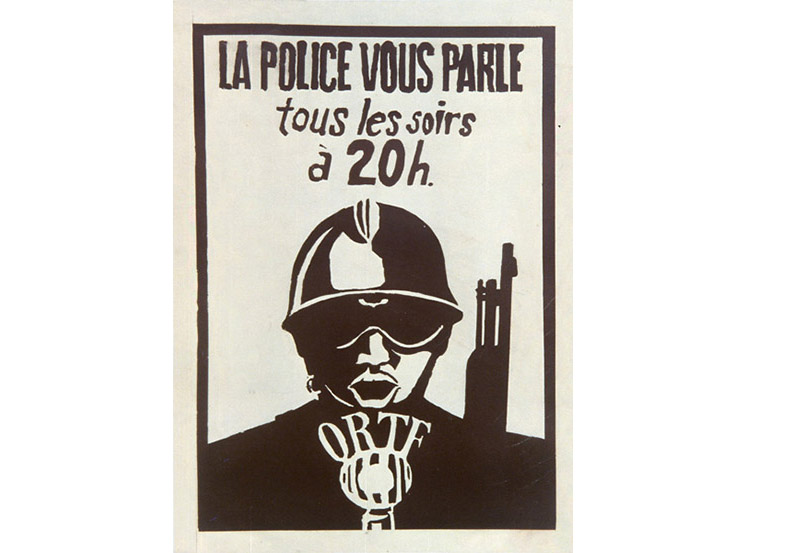

ORTF : La police vous parle tous les soirs à 20hn (ORTF: The police speak to you every evening at 8pm). Atelier Populaire, 1968. BnF, Département des Estampes et de la photographie.

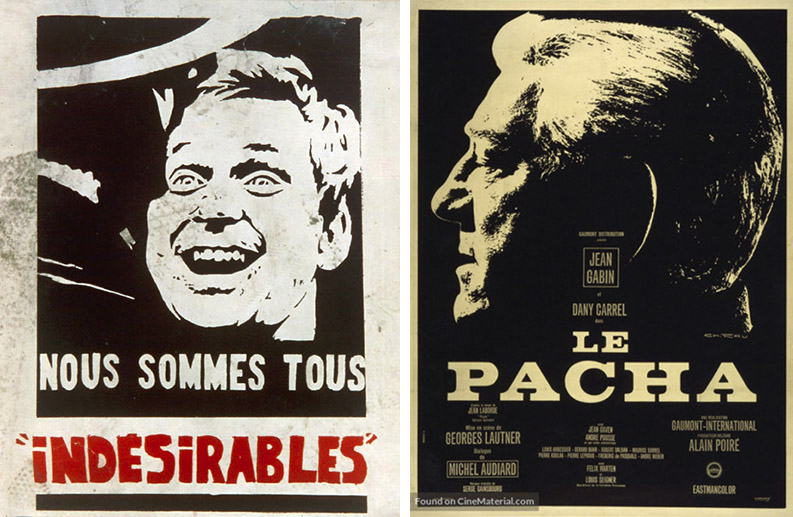

One way the Atelier Populaire adopted advertising methods was through their use of a similar visual styles. For instance, an anti-police poster reduces a menacing officer to shadows and highlights in a bold, reductive style, similar to recently commodified pop art, a topic which is thoroughly explored in Liam Considine’s 2015 essay “Screen Politics: Pop Art and the Atelier Populaire.” This simplistic style was used throughout the majority of the Atelier Populaire’s posters, both for its efficiency and clarity. Photographic posters were also printed by the Atelier, striking due to their realist depictions of students and workers. One such poster features Daniel Cohn-Bendit, the ascribed leader of the March 22 protests at Nanterre, which bears a resemblance to the movie poster for the 1968 film Le Pacha . In both cases, the posters use the face of a protagonist to represent a larger narrative. For Le Pacha, this was to create an empathetic connection between viewers and the film’s leading actor, Jean Gabin, an aging police inspector. Likewise, the depiction of Cohn-Bendit, young and defiant, also prompts sympathy from viewers, who were already shocked by the police’s brutality against Parisian students. The Atelier Populaire used the visuals of the popular media to bring representations of society back to the people, prompting an open dialogue of ideas, rather than the one-way messaging of popular advertising.

LEFT: Nous sommes tous indésirables (We are all indesirables). Atelier Populaire, 1968. BnF, Département des Estampes et de la photographie. RIGHT: Le Pacha. Charles Rau. 1968. CineMaterial.

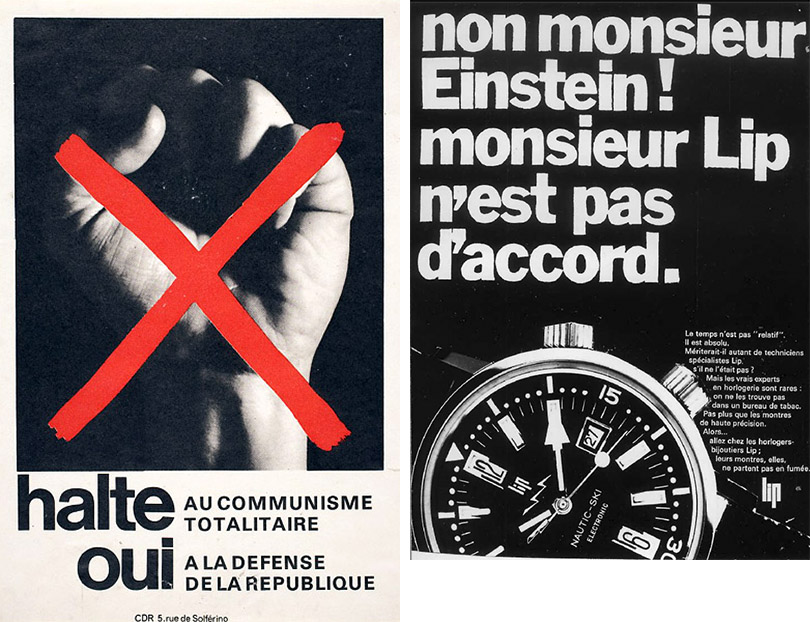

In addition to imagery, the Atelier Populaire also took from advertising’s use of typography and language in order to create effective slogans. Like imagery, written word plays into the overall scheme of popular advertising and slogans are often the persuasive punchlines to their graphic counterparts. Using the “universal,” sans-serif typeface Helvetica, the Atelier Populaire created several posters which echoed mid-century product advertisements. The dominant words, “halte” and “oui” are supplemented by explanatory text in a smaller size of the same typeface. This is similar to how Helvetica was used in many advertisements, such as in a 1968 magazine ad for Lip’s watches.

LEFT: Halte au communisme totalitaire - Oui à la défense de la république (stop totalitarian communism - yes to the defense of the republic). Atelier Populaire, 1968. BnF, Département des Estampes et de la photographie. RIGHT: Non monsieur Einstein! Monseieur Lip n’est pas d’accord (No mister Einstein! Mister Lip is not okay). 1968. Mnesys..

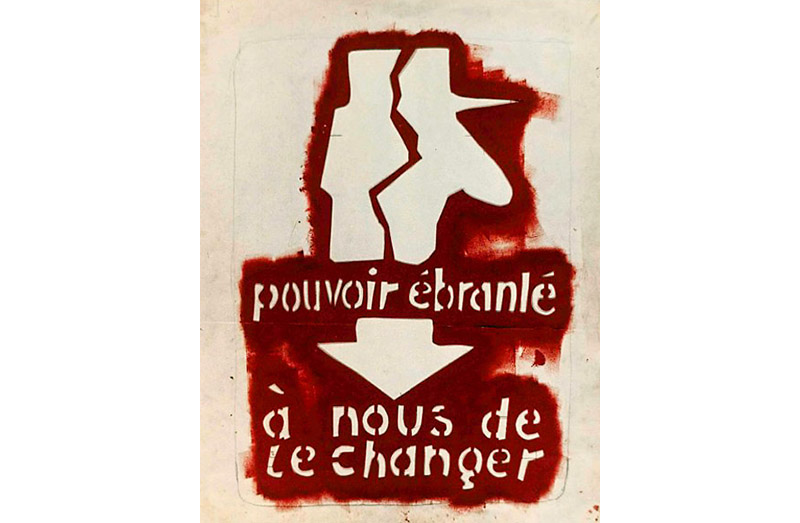

In terms of language, slogans printed by the Atelier Populaire were often direct and encouraged action. In one poster, the top line states an action that could happen, “pouvoir ébranlé” and the line below suggests the means of doing so, “à nous de le changer.” Similarly, a contemporary soft-drink advertisement reads at the top “organizez chez vous une PEPSI-BOOM” and below “écoutez europe no 1.” Capitalistic on two fronts (as Europe 1 is a privately owned radio station in France) the Pepsi advertisement encourages the consumption of goods through the solitary act of consuming media, whereas the poster by the Atelier Populaire encourages the breakup of such a system through collective action. According to Debord, on a spectacle society, common language, or language of persuasion, is what connects individual spectators to the organizing class. However, the Atelier Populaire distributed common language it to the masses, using its persuasive form to expose the state’s controlling bodies.

Pouvoir ébranlé, à nous de le changer (To rattle power, to us to change it). Atelier Populaire, 1968. BnF, Département des Estampes et de la photographie.

Finally, the Atelier Populaire’s lack of self-commodification allowed them to be truly “popular,” while still operating within the spectacle’s framework. Before anything was printed, daily general assemblies were held to vote and collaborate on designs and no final posters were signed by individuals. Instead, some were branded with a square stamp which read “ATELIER POPULAIRE EX-ECOLE DES BEAUX-ARTS.” Therefore, there was no “star system” from which to exploit the artists and, as co-founder of the Atelier, Philipe Vermès noted later, “Anybody and everyone—students, factory workers, office employees, transporters, media people, mailmen, fishermen—could bring ideas and work on the actual silkscreening.” The posters’ anonymity is very similar to the way designers of popular advertising also go unrecognized to the general public. However, rather than a faceless company advertising a product, the Atelier Populaire was a faceless movement that advertised ideas, encouraging the education rather than the hypnotic compliance of their viewers. Using posters, the Atelier Populaire worked against the effects of mass deception and anti-enlightenment that permeated popular advertising, while taking advantage of the anonymity mass media provided in order to promote an egalitarian movement, effectively reworking Theodor Adorno’s “culture industry.” “We all must teach ourselves,” wrote the members of the Atelier Populaire. “The bourgeoisie’s educative power thus challenged, the way will be open to the educative power of the people.”

Organisez chez vous une PEPSI-BOOM (organize at your place a PEPSI-BOOM). 1968. La Bande FM du Loriet.

Inspiring individuals and unions to think consciously about the conditions under which they were working, the Atelier Populaire’s posters became the graphic manifestations of the proletarian ideologies underpinning the 1968 riots. “We should work towards the development of a truly popular culture,” wrote the Atelier Populaire in their manifesto Posters from the Revolution, “that is to say of the people at the service of the people.” Not only did the posters express this sentiment, but the Atelier also embodied this ideology in their way of working. Through their non-specialist printing techniques, daily assemblies, and anonymity, the Atelier Populaire defied bourgeois culture, which they called, “The means by which the forces of oppression of the ruling class isolate and set apart the artists from the rest of the workers by giving them a privileged status.” Their new culture, which would break down the social division of labor and archaic hierarchies, would bind together artists, students, and laborers (although, it should also be noted that this call for the overthrow of hierarchical French class systems is not new, but falls in a long line of revolutions starting in 1789 and continuing today with the Gillets Jaunes protests.) Ultimately, the great contradiction of the 1968 riots is that, by the end of the summer, the movement had lost momentum, du Gaulle was still in power (at least until the following year) and changes in social policy were incremental. However, this should not, and does not, degrade the fact that for four weeks the country of France was forced to a standstill by a strike of students and labor unions, united not by a single leader, but by their conviction that society could change. The Atelier Populaire was essential in creating this bond, using words and images to bring people together. Today, when mass media is even more embedded into society than it was fifty years ago, it is important to consider how simple methods, like ink and leftover newsprint, can still make an impact on the way ideas are spread—and now we even have Instagram to push those messages beyond the street. As the Atelier Populaire declared, “LA LUTTE CONTINUE.”