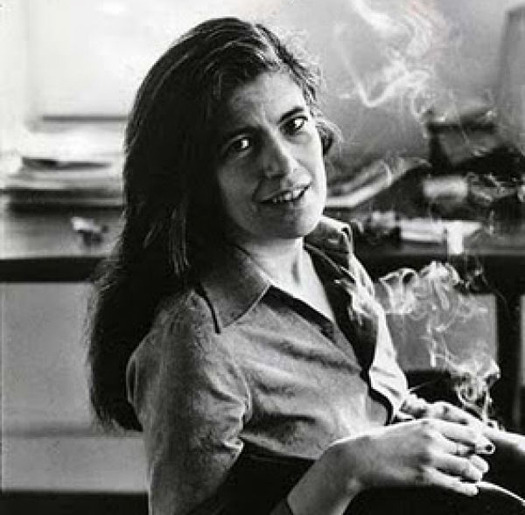

Photograph by Jill Krementz, from a print signed by Susan Sontag.

Over the years, as a designer, I have encountered an endless stream of CEOs, magazine editors, university presidents, and new media gurus — even a few Senators and a President. No one, however, scared me as much as Susan Sontag, who died yesterday after a long battle with leukemia. For more than twenty-five years I was her son's close friend, her occasional companion for dinner or a movie, and a fellow reader and book collector. I was never among her closest of friends.

But I was her graphic designer.

Susan was the most intelligent person I have ever met. She was intense, challenging, passionate. She listened in the same way that she read: acutely and closely. There was little patience for a weak argument. She assumed, often wrongly, that you possessed a general level of knowledge that would challenge even most college-educated professionals. She assumed you knew a lot and that you were interested in everything precisely because she was so interested in everything. Anything less left her unsatisfied, and, as she would not suffer fools, she wanted every encounter to be one in which she learned something.

Her interest in everything says a lot of my meetings with her over the years. There were early visits to her Upper West Side apartment in the 1970s, when I was still a young and impressionable student, in awe of someone who could own so many books (and who seemed to have read all of them). [The photograph above is from a print that hung in the Pomander Bookshop, our local bookshop in the 1970s. Long before it was popular, they specialized in the newest fiction from Latin America; Susan not only had read most of it already, she knew most of the the writers.]

My recollections of time spent with Susan Sontag have a great deal to do with her insatiable appetite for intellectual adventure, and perhaps it is this that has left its impression on me most of all. I remember a lunch in London, where she took me to a print shop and I bought two prints of Vesuvius by Sir William Hamilton. I would go on to collect volcano prints for another two decades, and Susan would later write The Volcano Lover, a novel based on the life of Hamilton. There were two Christmases in Venice, one spent in the company of the Nobel Prize-winning Russian poet, Joseph Brodsky, who took us on extended walking tours from church to church (anticipating his book on Venice, Watermark). Several years ago, we were at a wedding together in Washington D.C., and Susan insisted on stopping at the National Gallery of Art to see an Art Nouveau exhibition on our way to the airport. And just last winter, I met her to talk about a book project, but she rushed us off to the movies to see The Triplets of Belleville, the animated French film she had seen only days before. Finally, there was the recent dinner where she insisted, despite being weak from illness, on traveling across town for a feast by her favorite sushi chef.

Perhaps my most memorable evening with Susan was one when I came by to show her some book covers, and she invited me to stay for dinner. A mutual friend arrived, and Susan, who never cooked and seldom ate at home, served us dinner. It was all a set-up. She was so excited by some of her recent readings that she needed an audience to share her discoveries. Over dinner, she read us the first chapters of recently published books by Imre Kertész, Fleur Jaeggy, Anna Banti and Penelope Fitzgerald. She read aloud with a passion and urgency that eclipsed everything else around her. As dinner conversations go, it was, perhaps, a little one-sided. It was also an unforgettable performance.

*****

Susan Sontag will long be remembered for such enthusiasms, and I think it's fair to say that few writers have been as deeply involved or as influential in the cultural and political landscape of our times. Her apartment was full of carefully chosen objects, from many different periods and places, and her abiding interest in culture led to an appreciation of cultural artifacts. Mostly, though, she collected books: not as a rare book collector, but rather as the voracious reader she was. All of them were closely read and held, and at some point Susan came to care deeply about their design.

In the mid-1980s, Drenttel Doyle Partners designed a series of her books for Farrar Straus & Giroux. Susan had a favorite piece of art for each book. She always wanted to see what we'd propose, but it was hard to compete with what she had chosen, her selections suggesting, from her perspective at least, deep relationships to her writing. As a result, her first series was art-laden, boasting works by Isamu Noguchi, Andrea Mantegna and George Seurat. But there were also surprises: The Benefactor featured a work by Garnett Puett, a human form-like sculpture created by bee honeycombs, with the bees flying from New Jersey into the gallery in Chelsea, long before Chelsea had come of age as an art destination all its own. These books had all been published before, so Susan had had plenty of time for ideas and associations to germinate: and while the idiosyncratic art choices were generally hers, I learned a great deal in the process.

AIDS and Its Metaphors, our next project, was a new book and overtly a work about the language of illness. We used a passage from the book to create a typographic cover: "Infectious diseases to which sexual fault is attached always inspire fears of easy contagion and bizarre fantasies of transmission by nonvenereal means in public places." (Not an expected image; nor, perhaps, language that easily rolls off the tongue, but I think this cover was one of Susan's favorites.)

Fifteen years after this first series, Susan asked us to design a new paperback series of all her books for Picador. I agreed, with an unusual stipulation: the art on the book could have no meaning or association with the content. We worked with abstractions of images to create feelings and patterns and colors, and my conversations with Susan were purely about aesthetics — the beauty or sharpness or hue of an image. I used to look forward to these meetings: I think Susan loved getting lost in this unusual territory where content and language were less critical. While she was always the opera critic, I imagine seeing these covers were a bit like being awed by a beautiful stage set in the darkness of an opera house. This approach to bookmaking — less literal, highly subjective, even lyrical — was refreshing for me as well.

Earlier this year, Susan asked me to publish the speech she delivered upon winning the German Peace Prize. Literature is Freedom is a book I'm especially pleased to have made. In it, she writes: "To have access to literature, world literature, was to escape the prison of national vanity, of philistinism, of compulsory provincialism, of inane schooling, of imperfect destinies and bad luck. Literature was a passport to enter a larger life; that is, the zone of freedom. Literature was freedom. Especially in a time in which the values of reading and inwardness are so strenuously challenged, literature is freedom."

I have a more expansive view of the world from having read Susan Sontag's many books, from having worked with her as a designer and publisher, but mostly, from having known her. For so many of us, she was a lightning rod for ideas about everything: from illness and health to photography and painting to the politics of Vietnam, Bosnia, 9/11 and Iraq. In her writing, she insisted that we confront ideas in their full-fledged complexity. She deplored ignorance, and relished originality, creativity, imagination: but mostly what she championed was the importance of intelligence: "We live in a culture," she once wrote, "in which intelligence is denied relevance altogether, in a search for radical innocence, or is defended as an instrument of authority and repression. In my view, the only intelligence worth defending is critical, dialectical, skeptical, desimplifying."

As a designer, I relish every project I've done with her. She is my favorite author because she was so challenging, so fearless, so intelligent. She loved it all so much. And I loved her.