Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from Sean Adams’ newest book, How Design Makes Us Think (Princeton Architectural Press). The book explores why we respond to design in certain ways, and how designers use visual cues to create the response. For example, why do we think primary colors are friendly? How do we determine if something is efficient and why does that matter? These questions and more are explored by Adams in chapter addressing a specific communication: seduction, humor, love, anger, pride, and more. This excerpt explores humor: how it works, why we respond to it, and how designers use it as a tool to disarm the audience.

We are pleased to welcome Sean to our next Design Observer Community Session on March 30, 2021 when he'll talk about this book and take your questions. We hope you'll join us, tickets are available here.

As E. B. White stated, “Analyzing humor is like dissecting a frog. Few people are interested, and the frog dies of it.” Decoding humor is a tedious business. Philosophers have attempted to determine what is humorous and why for millennia. In the Republic (375 bce), Plato recommended that the leadership of the state should refrain from laughter, “For ordinarily when one abandons himself to violent laughter, his condition provokes a violent reaction.” Freud analyzed humor’s properties and suggested that repression and sexuality caused it. Regardless of why we find something humorous, it is an extraordinary tool for the designer.

First, a designer can get away with more if the message or experience is humorous. One commonality with most jokes, witticisms, and puns is the element of surprise. For example, here is a joke by the comedian Henny Youngman: “While playing golf today, I hit two good balls. I stepped on a rake.” This joke works because it walks us down an expected path, “While playing golf today...” and it provides action, “I hit two good balls.” The surprise is the action of stepping on a rake. The audience needs to imagine the scene visually to understand precisely which balls Youngman is describing. The surprise has a slightly off-color tone. We enjoy the unforeseen, the collision of our expectations, and the mental process.

People enjoy solving problems. It is inherent. We solve a problem and receive a rush of chemicals in our brain that produces a pleasant sensation. Humor asks us to solve a problem, then provides an answer in a way we did not anticipate. Comedy also invites us to be “bad.” Consider the typical heroic narrative, Odysseus in The Odyssey or Luke Skywalker in Star Wars. Heroic warrior characters follow the most virtuous ideals.

In contrast, Han Solo is funny. He recognizes a practical reality and an appreciation for more human activities such as drinking, eating, fighting, sleeping, and sex. He would subscribe to the wise Irish proverb: “It is better to be a coward for a minute than dead for the rest of your life.”

In Comic Relief: A Comprehensive Philosophy of Humor, John Morreall provides the example of humor as a tool to accept negative information. An example is this debt-collection letter: We appreciate your business but, please, give us a break. Your account is overdue for ten months. That means we’ve carried you longer than your mother did.

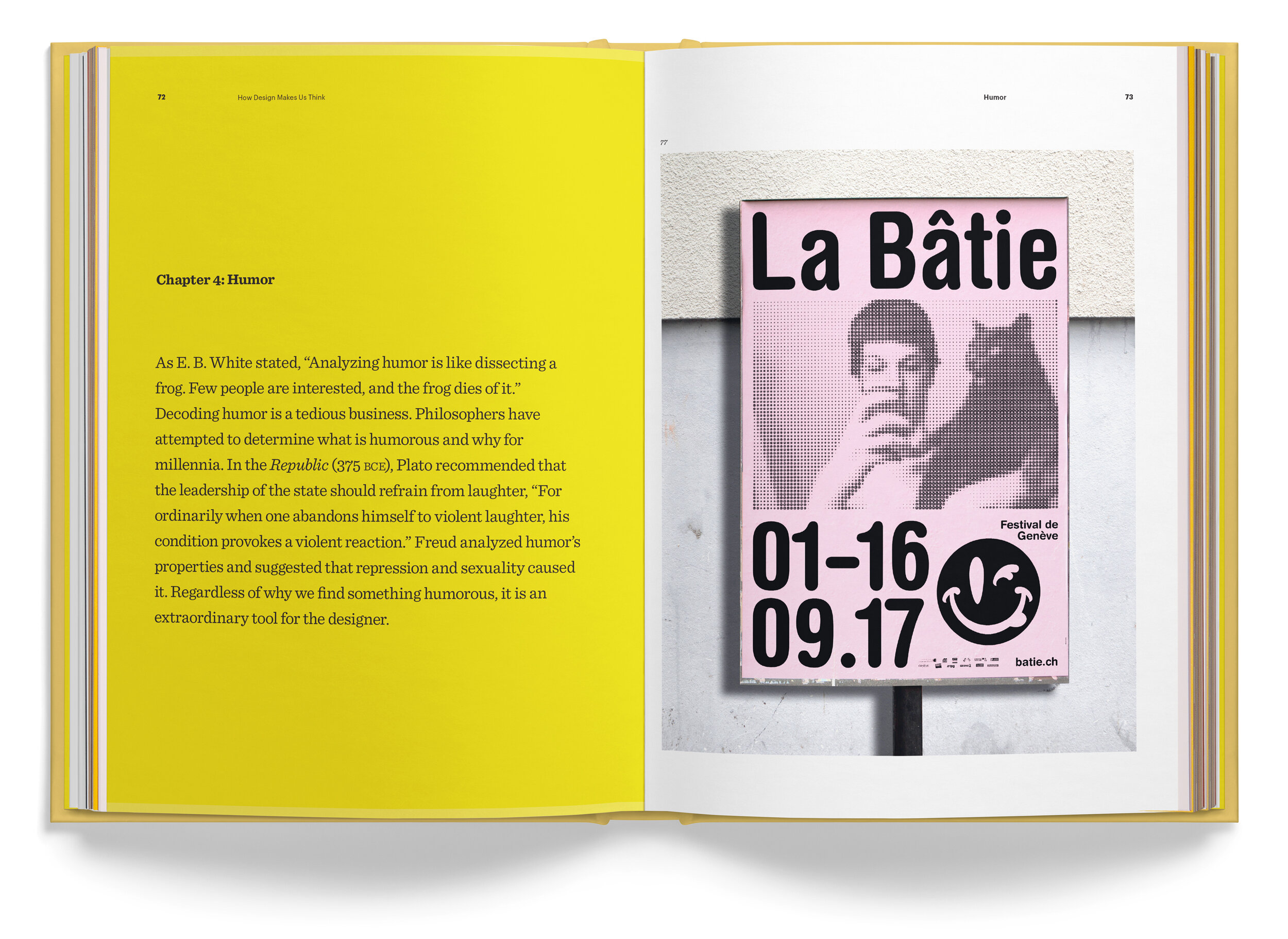

When a designer faces the task of communicating a complex, socially controversial, or unpopular message, he or she uses humor as a gateway into the message.