Linder, Untitled, collage, 1977

Most studies of collage published to date have tended to treat the subject in art historical terms. Today, collage is thriving but its enduring attraction goes largely unexplained. In a new book, Collage Culture: Readymades, Meaning, and the Age of Consumption (Rodopi), David Banash develops a theory of the origins and meaning of collage that views the combination of readymade elements as central to 20th-century culture. Artists in every medium, he argues, “turn to collage to respond to the possibilities and limits of an inescapable consumer culture.” In this email interview, Banash discusses the paradoxes of a practice in which critique and nostalgia intertwine in a dialectical embrace. Banash is Professor of English at Western Illinois University, where he teaches contemporary literature, film, and popular culture. He is co-editor of Contemporary Collecting: Objects, Practices, and the Fate of Things (Scarecrow), and writes cultural criticism for PopMatters.

Rick Poynor: What are the origins of your interest in the cultural meanings of collage, and how did you come to evolve the wide-ranging, interdisciplinary approach to collage that you take in Collage Culture?

David Banash: In the early 1990s, I went to graduate school to study literature, but I found that most of the really interesting scholarship was not happening in the confines of traditional concerns with influence, style, or narrowly national questions. Instead, people were reading across the whole culture of any given time. Literature had to be seen in the context of philosophy, history, the visual arts, the built environment, the material culture, and media technologies. I found all this incredibly exciting, but also a little bewildering. To hold anything together, one needed to think in larger concepts.

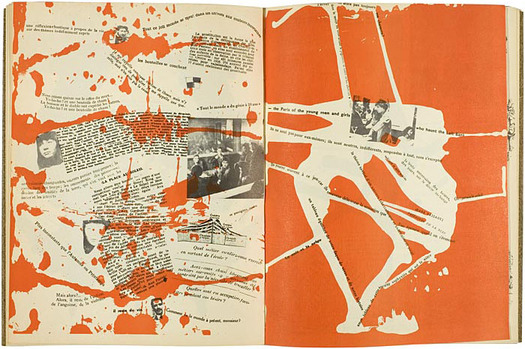

When I discovered Guy Debord’s work with the painter Asger Jorn, particularly their 1959 artist’s book Mémoires, I was struck with how a philosopher and a painter were speaking through collage. With Mémoires, the whole century suddenly came together for me as collage. I had a kind of epiphany: Tristan Tzara, André Breton, Ezra Pound, Walter Benjamin, William S. Burroughs, D.W. Griffith, John Cage, Kenneth Goldsmith, Andy Warhol, Steve Tomasula, just about any one I was interested in seemed to be cutting things apart and reassembling them. I started seeing the technique everywhere, and through Debord and Jorn I realized that to think about collage is not just to see a technique but to confront the whole century. Collage techniques tie together so many different art practices and economic relationships that, for me, it uniquely brings the century into focus. Collage is the 20th century’s cutting edge.

Guy Debord and Asger Jorn, spread from Mémoires, artist's book, 1959

RP: You argue that collage techniques allowed artists to uncover meaning within a readymade consumer culture and “find ways to evade, negotiate, reflect, or sometimes undo the reification of commodity culture.” That sounds full of possibility for resistance, but as the book unfolded I had a growing sense that, however collage has functioned historically, there can be no escape now from what you call the “universal code of capitalism” — that the medium’s radical intentions will inevitably be compromised by the inherent nostalgia of repurposing old material, so that collage itself becomes a kind of symptomatic display. To what extent do you believe that collage can have a critical purpose today?

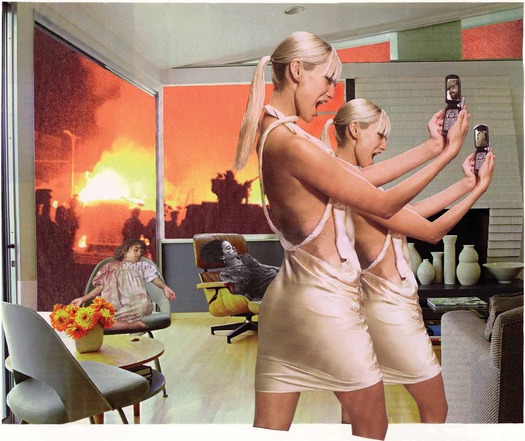

DB: Collage can still function critically by cutting into ideologies and making them visible. Linder’s work does this, as I’ve tried to show recently. Or consider Martha Rosler’s series Bringing the War Home. She cut together horrific war photos with the fantasy interiors of fashion and design magazines. With the Iraq War particularly, this was pointed, since the government’s message to U.S. citizens was to consume to drive the economy forward rather than sacrifice for the war. Her images show how completely gross that injunction to enjoy is in the face of suffering. She ruptures that ideological position really effectively.

Martha Rosler, Photo-op from House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, New Series, collage, 2004

And yet, while collage can cut into ideology this way, the very fact that one is cutting up fashion and lifestyle magazines that were themselves produced through a collage process of layout is telling. This is one of the paradoxes of collage. It has the power to be critical of ideology at the level of its content, but at the level of its form, it depends on the materials of consumer culture and quite literally re-enacts the exact processes of mass production and consumption. One can think this through from both sides. Like mass manufacturing, the artist works by producing fragments, literally parts, concentrating not on the whole, but on creating and manipulating the pieces, and most collage artists do this serially, creating huge files of images. Richard Hamilton and Joseph Cornell, for instance, would produce or collect whole categories of images (youth, watch parts, plastic toys, etc.). Then, in the moment of deciding on the final composition, bringing those fragments together in the pasting, one assumes the position of the consumer, selecting from all these complete, readymade fragments and assembling them into meaning in the same way one assembles a lifestyle. In this way, collage can be critical within consumer culture but it can never get outside it or figure some alternative world beyond it.

Richard Hamilton, “self-portrait” for the cover of Living Arts no. 2, 1963. Photograph: Robert Freeman

In the 20th century, collage techniques are seen as one of the ultimate marks of being avant-garde, and that only makes sense to me because they mirror the new modes of mass production and consumer culture. People recognized that the whole culture around them was cut-and-paste, from manufacturing to shopping. Today, the mark of the cutting edge in art is the digital, the virtual copy, and collage now seems to me to carry some of the uncanny magic that 19th-century illustration techniques or sciences carried for the Surrealists. Collage now seems to gesture towards a more emphatically or differently embodied past. As Marcus Boon has argued so well in his book In Praise of Copying, this new virtual work can get out of the commodity culture because it can exist at almost no cost and create a utopian, total availability. However, such work is always tied to digital technologies, and it will be tied at a formal level to whatever economic arrangements undergird that technology. For me, the same is true of collage because its materials are the materials of mass production and consumption.

RP: Yet, at the same time, the pervasiveness of digital culture — which I can’t see as separate from commodity culture, since it’s delivered to us by expensive commodities — appears to be driving an international resurgence of old-style physical collage made with paper, scissors and glue. This work has surfaced in recent books such as Cut & Paste: 21st Century Collage, Cutting Edges and The Age of Collage, and it’s all over the Internet. It’s often made by people who do applied work, design and illustration, alongside their personal art. What’s your view of this development and how would you explain it in terms of your book’s argument?

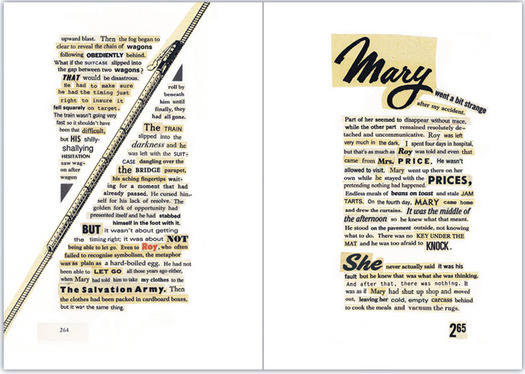

DB: In Collage Culture I argue that every collage is a dialectic of critique and nostalgia. In the cuts, there is always critique, a rupture, but every collage is also a nostalgic work of preservation. Different artists tend to emphasize one desire or the other. In Dada, the emphasis is almost always on the critical cuts, but in Joseph Cornell the emphasis is always on nostalgia, saving the fragments. What is so striking about this resurgence of collage is how work that makes radical cuts in the style of Dada now seems so nostalgic because the materials are so often drawn from the past. You can see this in work by John Stezaker, Christian Holstad, James Gallagher and Paul Burgess. Or consider Graham Rawle’s 2005 book Woman’s World, one of the most amazing collages ever produced, running to 450 pages of completely readymade language and image. It uses only phrases cut from women’s fashion magazines of the early 1960s to tell a story that those same magazines would never have acknowledged or printed. Rawle thus has the exact tones and even the exact topography of that time. His story contradicts the image of women produced by those magazines, so there is a hugely critical dimension to his work, but because the source materials so powerfully evoke that now lost world, the whole thing is pervaded by a profound nostalgia, a desire to hold on to something, to experience that world, and Rawle sustains that, keeping us in it page after page. In Rawle and many other contemporary collage artists, it is almost as if the critique becomes just a vehicle or an alibi for the nostalgia.

Graham Rawle, source material for the collage novel Woman's World, 2005 Graham Rawle, original typographic collages for Woman's World, 2005

Graham Rawle, original typographic collages for Woman's World, 2005

It really is striking that so many contemporary collage artists are not working in contemporary materials but instead turn to the archive of 20th-century print culture. I think in large part there is a huge nostalgia for that material culture because it is vanishing. Glossy magazines are a shadow of what they were, with their formats reduced and the commitment to design compromised by economies of every kind as print disappears into a virtual, online existence. In a way, the printed magazine image imposed itself on you; its large, physical presence was a constantly visible demand. In cutting into it, there was a profound reversal of power, so well described by collage artists like the writer Kathy Acker and Linder. It was possible to mutilate and mutate the spectacle. Though one can collage the online image, or Photoshop it, the mutilated copy is never there, and one never sees the dismembered corpse of the source material. The online image is deathless, forever available and forever pristine. I think this deprives one of a good deal of the pleasure and excitement of the cut.

Though most histories of collage see it as an invention of the fine arts, I argue that technology and the designers of commercial mass media in the second half of the 19th century created collage. The historical avant-garde revealed the power of the mass media’s cut-and-paste techniques through a radical, collage critique of the ideology disseminated by that media. It seems to me that contemporary collage artists are now seeing what we have lost as we move into a virtual media, and much of their work is a kind of loving and longing for the lost colors and textures, typefaces, forms, and aesthetics of yesterday’s printed world.

Where collage seems to me less nostalgic and more engaged is in urban street arts. There, far more contemporary material is used with tremendous critical energy as often readymade material is collaged on walls and the whole city becomes a kind of wild and inventive cut-and-paste work. Street artists are responding to the privatization of the city and the ubiquity of advertising. The works of Banksy and Swoon have profound collage dimensions that haven’t yet been critically explored, and there are many, many more anonymous examples, too. Your review of Allan Markman's recent book on the doors of New York shows this amazing energy, which seems to me worlds away from the melancholy nostalgia of so much contemporary collage.

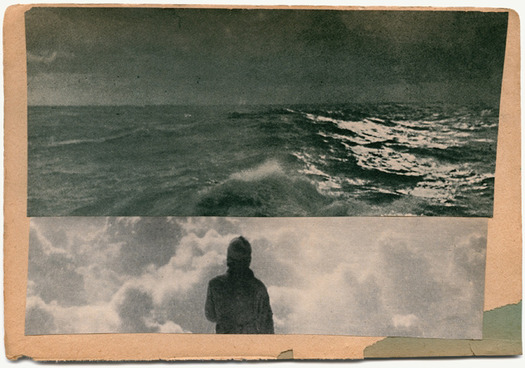

RP: The word “nostalgia” is loaded with negative associations and melancholy nostalgia sounds unhealthily fixated. One thing I see in physical collage is a return to the tactile pleasure of handling paper, and an acknowledgement that mass-produced images such as postcards and magazine pages also possess a compelling aura as time passes. Is this necessarily an enervating surrender to nostalgia? Could it be instead an intellectual and emotional desire to evaluate and find meaning in the vast, ever-accumulating archive of our shared cultural memories?

DB: I actually think that nostalgia is incredibly powerful, and not necessarily negative at all. When I say melancholy nostalgia, I have in mind work that seems to just rehearse the vocabularies and gestures of the historical avant-garde without revealing those new meanings that are waiting in the print archive. Nostalgia itself, however, is incredibly powerful because it is a desire for the past, and it turns our attention to what has been lost and holds onto it, keeps it from slipping away — which in a capitalist context of disposability can itself be a kind of resistance. As a nostalgic practice, collage is capable of reactivating our whole material culture in really compelling ways. For instance, in his “bibliolages” William Davies King seems to me to be doing all he can to hold on to an archive of the past, and that is deeply connected to his practice as a collector. His materials are so varied, and put together with such incredible visual energy, I think they do reveal the archive in new ways, but his collages don’t look or feel like mere repetition of the historical avant-garde.

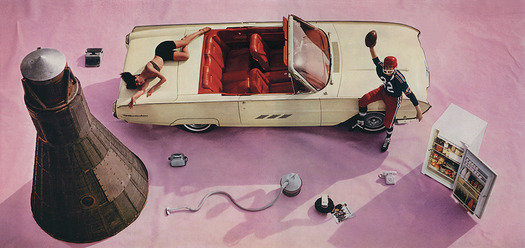

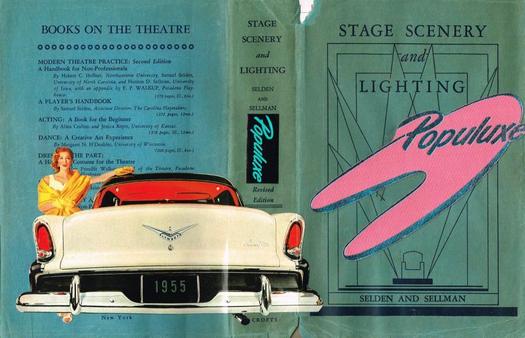

William Davies King, Populuxe Scenery and Lighting, ruined book bibliolage, 2013

So, for me, nostalgia is not at all negative, but rather as Susan Stewart and Gaston Bachelard have it, a way of idealizing the materials of the past into experiences of immediacy and authenticity, and this ultimately can lead to what Walter Benjamin calls profane illuminations, those sudden insights where the past’s own imagination of itself, its utopian dimensions or its relation to the present, are suddenly revealed by the collage.

RP: You say that every collage is a dialectic of critique and nostalgia, but what about the aesthetic dimension of contemporary collage? This is clearly of great importance to people making collages, and I doubt that in many cases they are giving much conscious thought either to critique or nostalgia. There’s a sense in Collage Culture that the theory can account for anything we encounter in a collage, and this could make the medium seem like a dead end because we know in advance everything it can do. For me, some collages have an aesthetic power that exceeds and survives any explanation we might bring to them. Is the degree of aesthetic resolution in a collage significant for you, and how do you respond to this visual dimension when the theory is always there to impose itself on the looking?

DB: Fredric Jameson always says that to the degree the theorist wins, the world loses, since it seems that one has decided everything in advance. However, I truly hope that this is not the case with Collage Culture. When I write about Simon Rodia’s Watts Towers, for instance, I invoke the overwhelming aesthetic achievement. I’ve also really paid attention to that with Linder’s work, where I try to articulate how the friction of the concepts is only riding along on the overpowering frisson of the visual spectacle. In my writing about the work of Sarah Sze that aesthetic dimension is hugely important, and literally walking into her assemblages have been some of the most intense aesthetic experiences I’ve ever had.

Sarah Sze, Things Fall Apart, mixed media, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2001

However, I think that the aesthetic dimension of collage has in fact been at the forefront of most critical writing. This is true from Max Ernst’s Beyond Painting to William Chapin Seitz’s The Art of Assemblage, or to a degree even in Brandon Taylor’s recent Collage: The Making of Modern Art. What has been less clearly articulated is why collage became so important to the 20th century in so many mediums, and why it was also seen for so long as a mark of being modern. I answer that question by focusing on the meanings of collage at the level of its techniques and materials, and investigating how it functioned in relationship to the emerging world of consumer culture. I certainly do not think those are the only things to pay attention to, but I felt so little writing had addressed those questions in depth. Collage was too often seen only in its critical dimensions, or only in a single medium, and there wasn’t a compelling account of how collage works as nostalgia in its ability to preserve and reactivate the archive.

A dialectic is not static, either, but a continually moving tension, and rather than merely decoding a work of art, I hope that my writing registers the tensions that the compositions stage and balance. For instance, I was always fascinated by Duchamp’s comments about the Bicycle Wheel, which he talks about as the flickering flames of a fire that for him produced a sort of daydream. To me, his observation is key to that work, since it puts the wheel in both literal motion and a kind of affective motion. It seems to me that Duchamp is staging a nostalgic evocation of the experience of home but balancing it against the coldness of the mass-produced wheel and its industrial modernity. He is cutting those two things together, and getting us to think about how we are becoming at home in the mass produced. Obviously there is so much more in Duchamp’s work, but his account of it as an affective experience is key to my reading of it, though I would never claim that any reading could exhaust the work of art. Indeed, it is the art that always ends up exceeding the writing, which is why work like Duchamp’s lives on, to be written about again and again.

RP: Despite its breadth of reference, Collage Culture primarily focuses on fine artists’ use of collage techniques. What do you make of the widespread embrace of paper-based collage in the past decade by an international community of image-makers who don’t necessarily belong to the formal art scene? I’m thinking of work produced by collagists such as Katrien De Blauwer, John Gall, Nils Karsten, or James Gallagher, who you mentioned earlier. The Weird Show website has many examples. Is this post-20th century, digital-age enthusiasm for collage a temporary trend, or do you expect the medium to exert a hold on visual form-makers into the foreseeable future?

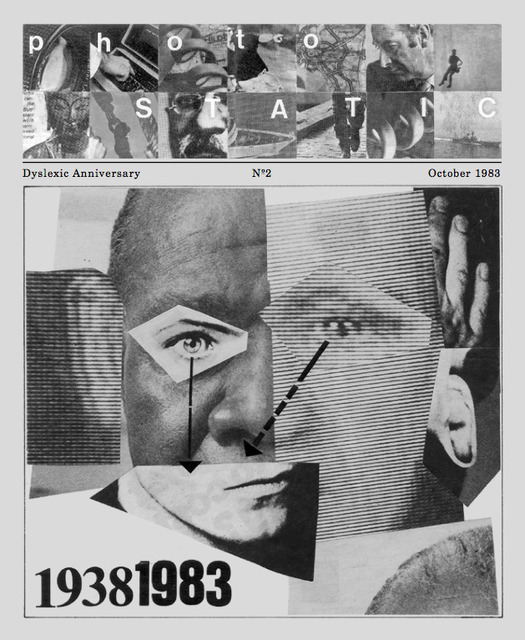

DB: The web is making new collage work by outsider artists wonderfully visible, but I also think this is not nearly as new as it might at first appear. The work you see on sites like The Weird Show must be understood in a longer historical context. In the early 1980s, punk subcultures produced an incredible number of do-it-yourself zines in which people were taking up scissors and paste to create their own alternative media, and the visual language of that subculture was collage. For instance, PhotoStatic magazine ran from 1983 to 1998, and it reproduced incredible collage work that was coming from this aesthetic.

Cover of PhotoStatic no. 2, 1983. 79 copies printed on a Xerox 9500 xerographic duplicator

One can even go back as early as the 1960s, when the mail art movement was beginning. Few people write about mail art because you had to stumble across it, and if you wanted to receive art you had to also make your own and send it out. The visual language was absolutely based on collage, and if you look at what has survived in a few archives, it has a great deal in common with contemporary outsider collage. So there were thousands of people sending mail art and making zines, and to me the fact that most of them were outsiders to the official art world really shows that picking up scissors and paste was a way of working with and against the materials of what Guy Debord calls the spectacle. Also, I think we should emphasize the radically open nature of collage. To make collage you do not need expensive tools, or training, or even need the ability to draw. Collage takes the radical availability of texts and images in consumer culture and transforms that material from a demand to consume into an invitation to produce. With only a blade and some paste, absolutely anyone can enter into the practice of art and potentially produce really powerful work. This is not to say there aren’t virtuoso collage artists but rather to emphasize how open the form is.

Today, anyone with a Facebook page is essentially a publisher, so creating collage seems to me to be less of a response to the monolithic nature of the media spectacle than it was for the PhotoStatic artists. Now it gains far more of its energy from an engagement with the very nature of its materials, especially where there is so much seamless digital imagery. The embodied, tactile sense of collage is, as you suggest, found in the pleasures of working with paper, or making unique works, preserving and reactivating the print archive, and experiencing the frisson that comes with pasting one thing next to another. You can see this in Katrien De Blauwer’s work, where the ragged edges, folds and tears are so obviously emphasized. Even reproduced on the web, it is its materiality as paper that makes it leap off the screen.

Katrien De Blauwer, from the series Loin, collage, 2013

This is really well put by Linder. She writes, “That’s the trick about collage, you’re working with two opposing techniques — the ability to make a clean cut and the ability to avoid a sticky mess. Depending on the glue you use, you get one go at getting each piece of the collage exactly in place. I practice Zen and the Art of Making Things Stick.” This is the exact opposite of the digital world, where every choice can simply be reversed with a click. It is the gamble of the embodied moment. So, rather than collage being primarily an ideological struggle to articulate alternative meanings, I think much contemporary work is an ontological struggle to experience our bodies in relation to materials in the physicality of the cut and paste.

Collage Culture: Readymades, Meaning, and the Age of Consumption by David Banash is published by Rodopi.

For more on collage, see also:

On My Shelf: Fin de Copenhague

The Art of Punk and the Punk Aesthetic

Collage Now, Part 1: Sergei Sviatchenko

Collage Now, Part 2: Cut and Paste Culture