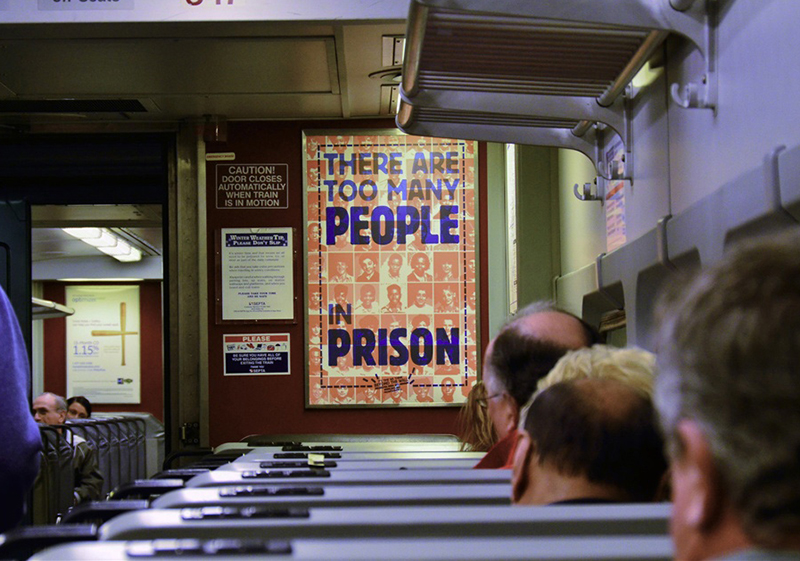

Rikers Island, the penal colony in New York’s East River, is an unforgiving presence for those incarcerated and their visitors. The over-crowded complex has been the focus of much criticism, and recently there have been calls for its permanent closure. Josh MacPhee, an artist, designer, and cofounder of The Interference Archive, became involved in agitating against incarceration twenty-five years ago, initially in support of political prisoners, then against the extreme isolation of super maximum security prisons. In 2013 MacPhee was invited by Philadelphia Mural Arts to use design to extend the reach and audience of a mural project they were developing around ending mass incarceration. This eventually led to a series of large scale public service announcements that ran on Philly’s commuter trains and public transit system.

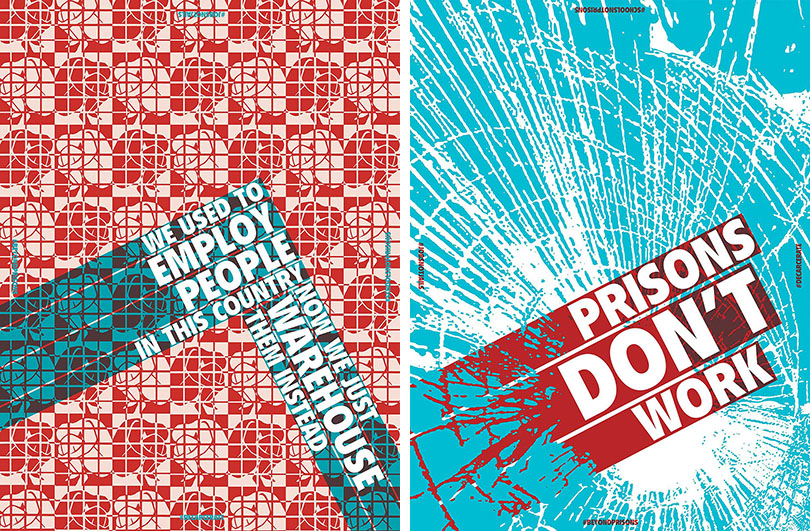

In 2015, Aaron Huey from the Amplifier Foundation approached MacPhee about turning these adverts into a series of offset printed posters that could be easily distributed across the country. He did that, and soon they began popping up around the US. (The above image is from Seattle):

While creating these posters was enjoyable, “I really wanted to plug into an actual campaign,” MacPhee told me, “something connected to the work people were doing on the ground to combat mass incarceration.” In early 2016, MacPhee joined forces with Gabriel Sayegh—one of the founders of the Katal Center for Health, Equity, and Justice—who laid out the early stages of the campaign to close Rikers Island Jail Complex. “I was convinced that it could work, and jumped on board right away. Thankfully I was also able to convince Aaron and Amplifier to support some of the work I would do with the Close Rikers Campaign.”

New York’s jails are designed to some extent as a deterrent, but Rikers Island is many things to many different people. “To most of the people incarcerated there, it is part of a broader socio-economic system that keeps them impoverished and struggling to maintain some modicum of control over their lives,” MacPhee explains. “For the guards, it’s a shitty job that none-the-less allows them to feed their families and stay a step ahead of the people they are guarding. For politicians it is a place to make invisible their failure to have the political will to confront the fact that our society has chosen to lock people in cages rather than address issues of systemic poverty and racism. For the rest of us, it is a ‘no place’ that allows us to ignore the real human costs of our relative privileges in a brutally hierarchical system.”

MacPhee has strongly committed to ending Rikers tragic realities yet, he notes, “I’ve only provided cultural support! . . . the original architects of the campaign, largely Katal and another organization called Just Leadership, came up with a strategy to put immense pressure on Mayor DiBlasio to shut down the jail complex.” This strategy, MacPhee explains, “was made up of a complex set of tactics that included mass demonstrations, immense amounts of media attention, taking advantage of official reports critical of Rikers, and popularizing particularly intense stories of the brutality of Rikers.”

This is illustrated by the case of Kalief Browder; he was incarcerated at Rikers in 2010 at age 16 for supposedly stealing a backpack, and spent three years inside, two of those years in solitary confinement. His case was eventually dismissed, and he was never convicted of a crime. While at Rikers he attempted suicide multiple times, and eventually succeeded after he was released in 2015.

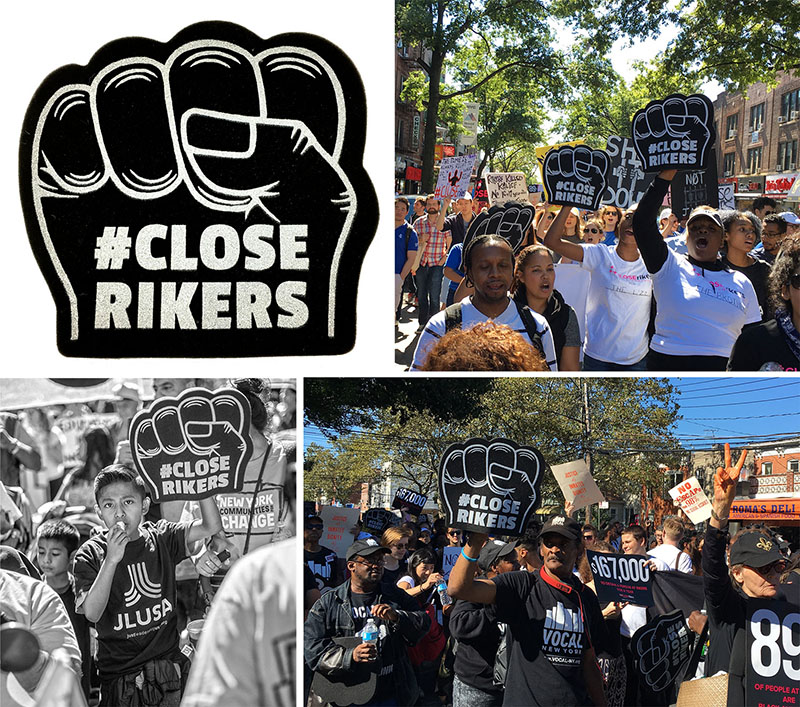

“One of the first projects I did with the campaign was to design and develop foam fists as a protest prop, which were used in a massive march through Queens to Rikers Island in the Fall of 2016.”

MacPhee actually never stepped foot on Rikers, but has visited people in half a dozen jails and prisons in as many states. “They are all different, but they function on the same basic logic, to warehouse people that have been deemed unproductive and un-useful. And once you’ve accepted the logic that some people deserve freedom while others don’t, it is an easy slope to roll down, compounding the belief that those that are incarcerated are somehow less human, and therefore deserve whatever conditions and treatment they get.”

As a visual social activist MacPhee’s goal is twofold: First, he uses culture to support those directly effected by Rikers, “primarily those formerly incarcerated there, their family members, and people from the communities that make up the majority of those at Rikers,” he says. “While the foam fists were great for getting media attention, more importantly they have been extremely popular with campaign members, generating a very creative sense of empowerment. I also designed a T-shirt for the camapaign, and partnered with Kayrock Screenprinting in Brooklyn to teach campaign members how to screenprint their own shirts.”

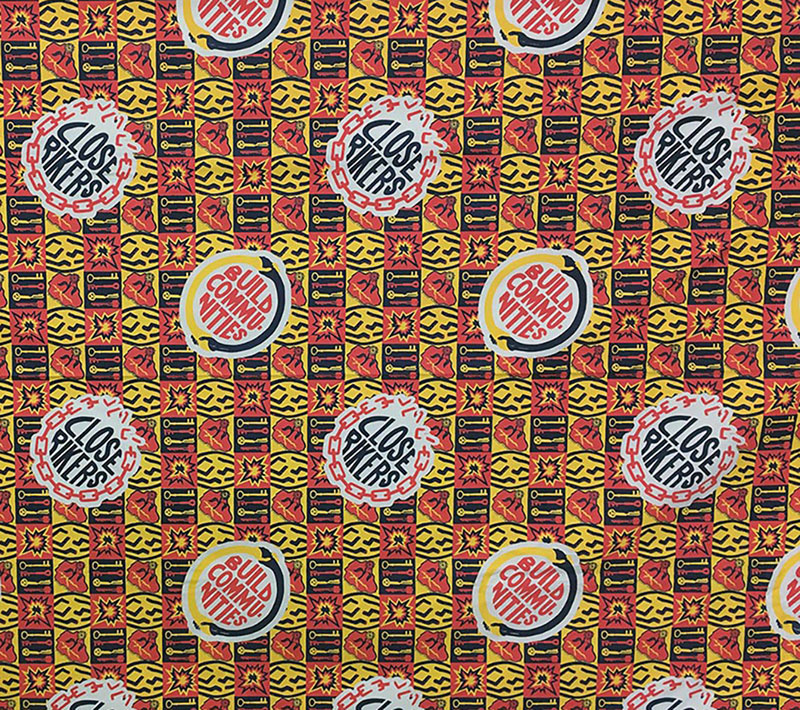

Second is to popularize the idea that Rikers should be closed within the general public. “To this end, I’ve worked with the campaign to produce a wide variety of cultural materials, from the above mentioned shirts to buttons to posters to postcards. In the Summer of 2017 I designed and had printed bolts of fabric with a “Close Rikers” commemorative pattern. Modeled after African commemorative cloth, the fabric has been used in a variety of contexts, including yardage being made available at the 2017 AfroPunk Festival for festival goers to cut off pieces to sew into patches, armbands, head wraps, and more.”

Have these interventions made a significant difference? “I don’t know if my actions personally have made a difference, but the campaign certainly has. Within a year of launching it, the Mayor announced that Rikers would be closed, and that is already slowly beginning to happen.” But this shift in penal policy is only the beginning. “I have been working more closely with the Katal Center, who have turned their attention to demanding pre-trial justice, to try to stop the pipeline of people going in to Rikers in the first place. So far this has most visibly been active in the lobbying realm, trying to force the NY State Legislature to pass meaningful bail reform and what is called a 'speedy trial' law to prohibit what happened to Kalief Browder. I worked with local letterpress printer Wasp Prints to create series of wood type placards that have been used extensively in this lobbying work.”

MacPhee recently designed shirts for Katal’s harm reduction campaign, which state “Harm Reduction + Organizing = Community Self-Defense.” An emerging city-wide campaign continues to demand a swift closure of Rikers and fights against any new jail construction. Meanwhile effective organizing is addressing the pipeline that brings people to Rikers, through pre-trial justice, what is called “pre-arrest diversion,” and police reform.