Portrait of Dori Tunstall, Dean of Design OCAD University. Photo credit: Martin Iskander

This interview is part of an ongoing Design Observer series, Chain Letters, in which we ask leading design minds a few burning questions—and so do their peers, for a year-long conversation about the state of the industry.

It‘s August, while it's still crazy hot and we'd all like to be poolside, it's time to think about heading back to school. This month, we examine design and education, and look at how education will shape the design discipline of the future.

Elizabeth (Dori) Tunstall is a design anthropologist, public intellectual, and design advocate. She is the Dean of the Faculty of Design at OCAD University, thus the first Black dean of a faculty of design anywhere. Dori has taught at Swinburne University and the University of Illinois at Chicago. She directed the U.S. National Design Policy Initiative and Design for Democracy. Industry positions include UX strategist for Sapient Corporation and Arc Worldwide. Dori holds a PhD in Anthropology from Stanford University.

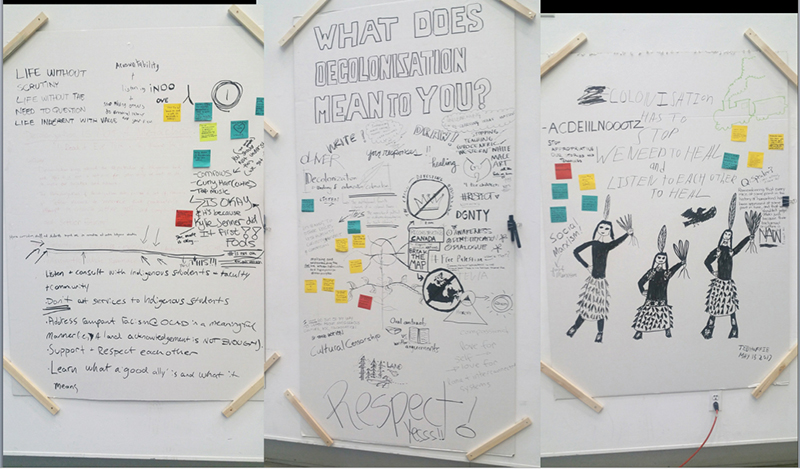

OCAD University students respond to the question posed by “Dean Dori”, What Does Decolonization Mean to You? (2017). Photo credit: Dori Tunstall

How much emphasis do you place on “real life” project-based learning as compared to theoretical design study?

As a design anthropologist, I believe design translates values into tangible experiences. Thus, I am a strong advocate for the term praxis as the combination of theory and practice to be centered in design education. In the words of Alan Barnard, theory is just merely a set of “questions, assumptions, methods, and evidence.”

“Real life” design projects are organized around a set of questions, assumptions, methods, and evidence. Real life design projects might be deeply embedded in ideas of capitalism, the exclusion of diverse peoples, the denigration of female and non-binary genders, and human supremacy over the environment. Even the most “practical” project should be critically examining these ideological positions before we design them deeper into the social fabric. Practice is significant because it makes sure theories are tested against the contexts they seek to describe. We can talk about gender inequality, but we should also be actively designing for example, non-gender specific products, communications, and environments. I would be suspicious of any design class that was not based in praxis.

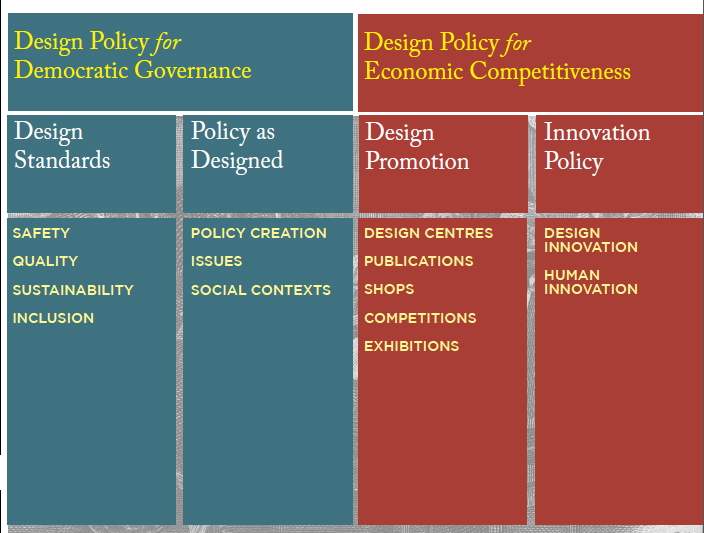

Dori’s Framework for the U.S. National Design Policy Initiative (2008). Designed by Matt Muñoz.

In November, AIGA is publishing “Designer 2025,” the culmination of research led by Meredith Davis and other leaders across multiple sectors, which will identify seven emerging trends with long arcs of influence and describe key competencies necessary to compete in the coming decade. All this begs the question: How can teachers prepare their students for jobs that don’t exist yet?

I prepare students to do meaningful work in the world. My engagement with design and design education was late enough (i.e. early 2000s) that I have never seen design as vocational. Because the focus of my praxis is interdisciplinary between design and anthropology, I have actively created every job I’ve had whether as a user experience professional when people did not know what that meant; as a design anthropologist, which people still do not know what that is; and now as the first Black and Black female Dean of a Faculty of Design anywhere, which is completely uncharted territory.

The “how” for me is in preparing students in have (1) the ability to know and refine their own learning processes; (2) to develop critical reflection and translate it into action; (3) to build confidence in their abilities to make their ideas real and positively impactful, and (4) most importantly, to engage in their relationships with humility and kindness towards everyone and everything. Designing is not about a job. Design is one of many pathways for doing meaningful work in the world.

Designing is not about a job. Design is one of many pathways for doing meaningful work in the world.

There are so many resources available online—YouTube tutorials, MOOCs, an endless supply of design blogs. Does this indicate that learning been democratized, in that there are many ways to get to the same end destination—a position in the design field? Or, has decentralized learning created a lack of a cohesive set of standards?

The phenomenon of YouTube tutorials, MOOCs, design blogs, online learning platforms has only changed two things for me in the design field. First, you do not have a direct relationship with the person from whom you might be learning. Second, there is more design “noise” to distract designers and clients.

The change in relationships have both positive and negative outcomes for the field. To the extent to which you had to learn directly from a European or Euro-American white male to be successful in design, these digital platforms raise the potential for other avenues of learning, especially for Black and Indigenous designers who continue to experience institutional racism in their access to design institutions. Here, I think of Neebinuakzhik Southall’s The Native Graphic Design Project or Maurice Cherry’s Revision Path podcast site. Or they can provide access to those who don’t live in the urban centers where design is often concentrated. Thus, the breakdown of one group’s monopoly on the relationships for design learning can be a very good thing. On the negative side, the lack of direct relationships with a community of learning could lead to greater isolation, when sometimes design work can already be isolated.

The increase of the design “noise” means that, while there are many paths on how to do meaningful work using your design knowledge and skills, it is more difficult to find your own unique path. My life’s work has been about showing that there are multiple very culturally-specific standards of design and other forms of making. We need better ways to help people find the path for them as students, professionals, and potential clients.

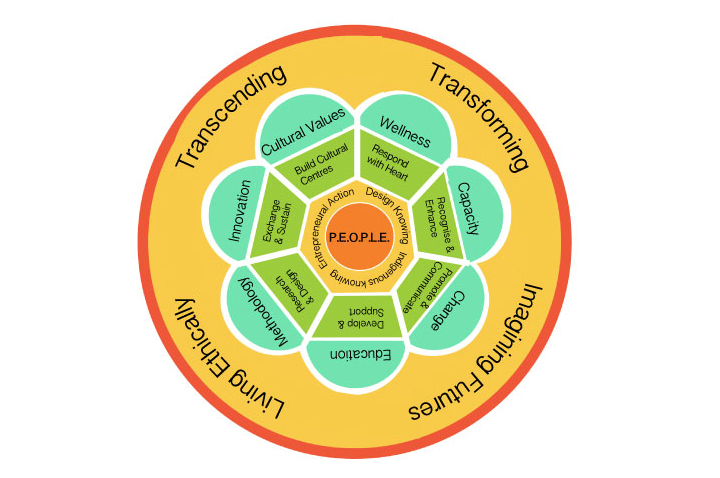

The Cultures-Based Innovation Mandala with P.E.O.P.L.E. (Peoples, Environments, Opportunities, Priorities, Languages, and Experiences) at the center. Designed by INDI Design.

When you reflect on your body of work to date, which has the most personal value for you? Why? All my work has had deep personal value for me because I am co-designing the conditions of possibility through community building. Highlights have been the US National Design Policy Initiative, the Design Anthropology postgraduate programs at Swinburne University in Melbourne, and the global Cultures-Based Innovation group. I love my music videos, Danthro Rap, QAME Song, and Danthro Garba, in which I’ve tried to explain complex design anthropological concepts through song and visual image.

Right now, my life’s work culminates in the effort to decolonize design at OCAD University. This requires separating the concept of design for the “modernist project” in order to cede more space for alternative ways of making and being from Indigenous, Black, Asian, Latinx, and Middle Eastern communities. By the modernist project, I mean the ethos of erasing ethnic, racial, and national identities to become universal man and the use of technology to achieve social and economic progress. While in the context of the first half of the 20th century in Europe, this project was utopian and revolutionary. In the context of 21st century North America, this project, in which design has been deeply embedded, is implicated in the cultural genocide of Indigenous peoples in North America, as well as all over the world, and the over-extraction of natural resources resulting in our sustainability crises.

This year, the effort to decolonize design at OCAD University has led to the successful hiring of three tenure-track Indigenous faculty as part of an Indigenous cluster hire. I have launched a Black Youth Design Initiative, which builds intergenerational networks of Black care to further develop design capacity within the Black communities. The premise is that design builds confidence in your ability to imagine, make (real), and connect to others in order to have positive impact. Thus, design could be an effective tool to fight anti-Black racism, because what racism systemically erodes in Black people is that confidence.

The premise is that design builds confidence in your ability to imagine, make (real), and connect to others in order to have positive impact.

Talk about a professor that improved your design approach. How did they do it?

Lauralee Alben was never my professor, but through one 8-hours conversation she changed my understanding of the possibilities of design. Lauralee is a designer and executive coach who runs the Sea Change Design Institute. Her approach uses the living system of the ocean to provide a design framework for organizational transformation. Her expansive view of design helped crystalize how design combined with my anthropological training could be an ideal tool for facilitating the transformational shifts in which I was engaged at the time through Design for Democracy and the US National Design Policy Initiative.

She imparted the wisdom to me that one should define your intentions as a question instead of a statement of goals. By doing so, you remain open to the myriad of ways in which you can accomplish that intention as opposed to locking yourself into the binaries of success and failure to accomplish a goal. This wisdom I still impart to my design students so that maintain the focus on their intentions in the world, but accept that there are many ways to move. I never imagined when I was a PhD student in Anthropology at Stanford that I would be leading a Faculty of Design at OCAD University.

Screen grab of Dori’s QAME Song music video on Youtube. Everything by Dori.

From Gail Anderson: A well-respected author has written a book that sounds interesting. You finally track down a copy and the cover is hideous. How much does a bad cover influence your book buying decisions?

I am primed to notice a publisher’s attention to form as well as content, so book cover design definitely influences my purchase decisions. I recognize that authors may not have a lot of control over the design of their books, so a hideous cover design would not prevent me from buying a book. At the same time, a beautifully design book cover with empty content would be passed over as well. Ideally, I am most likely to purchase a book in which there is a harmonious relationship between the cover design and my expectations of the content. If the story being told is hideous in nature, then a hideous cover might be appropriate and thus exciting. A book that is well designed enables me to accurately judge it by its cover.

Next week Dori asks Zach Lieberman: We harness the computing power of digital technologies to often perform work that we no longer value having humans do. The anxiety that drives the plot of the Matrix, Terminator, or Blade Runner series is the reversal of the human as master and technology as slave relationship. If you were to design a new system of technologies based on a non-hierarchical relational model between humans and technologies, upon what phenomenon would you base that model? Please speculate on how it would change your current creative practices.