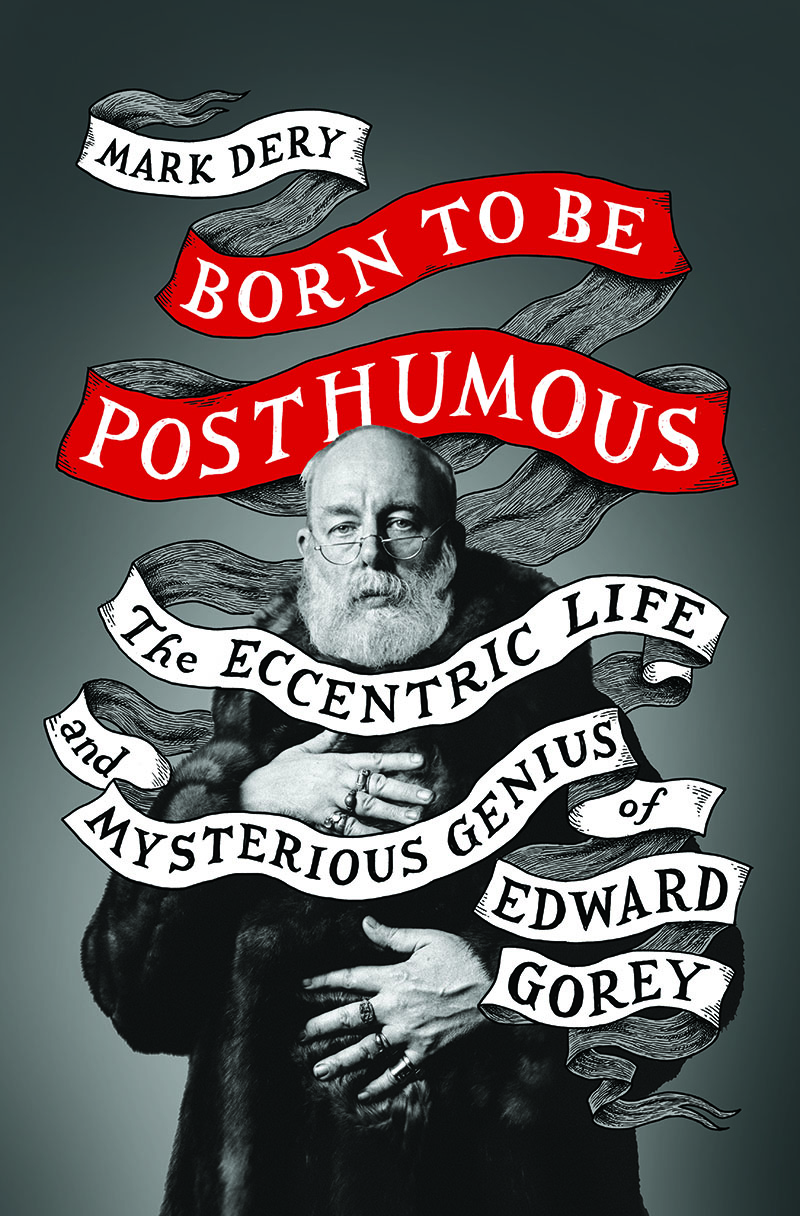

Mark Dery, a sharp cultural critic and keen research sleuth, is a pleasure to read and listen to. His vocabulary transcends the commonplace and his knowledge is encyclopedic. The titles of two of his authored books The Pyrotechnic Insanitarium: American Culture on the Brink and Escape Velocity: Cyberculture at the End of the Century and Culture Jamming: Hacking, Slashing, and Sniping in the Empire of Signs, speak to his erudition. The title of his essay collection I Must Not Think Bad Thoughts underscores his wit. His latest volume, Born to be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey, is equal to the beloved idiosyncratic life of his subject. Having known Mr. Gorey, been a fan of his crafty illustrations and writings (and I even wrote the essay for Edward Gorey: His Book Cover Art & Design), I have a vested interest in what Mr. Dery uncovered and ultimately covers it in his book. This interview examines the whys and wherefores of his seven-year plus investigation . . . and for me it is as entertaining and enlightening as the book itself (although not a substitute).

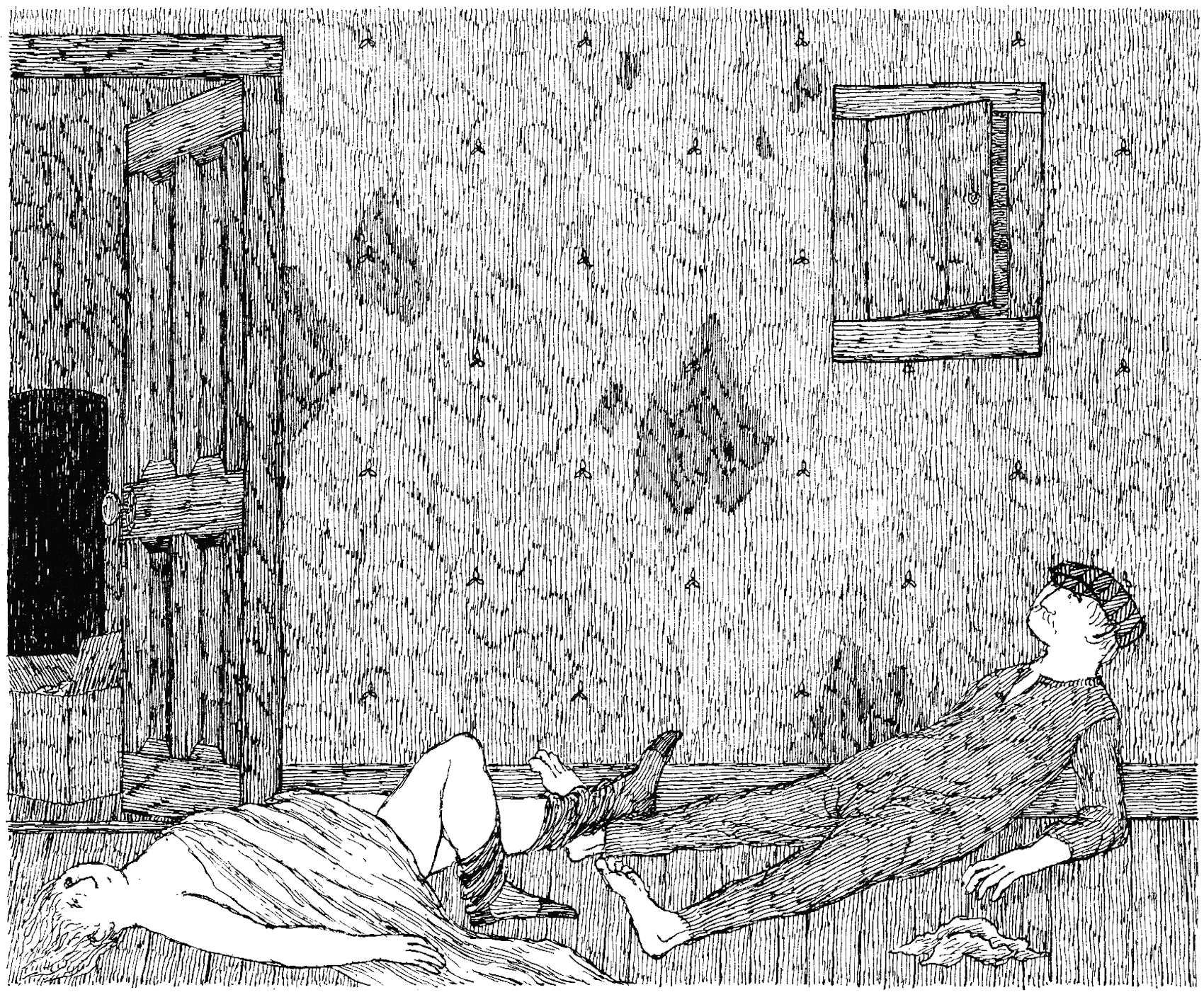

'When they tried to make love, their strenuous and prolonged efforts came to nothing.' The Loathsome Couple. (Dodd, Mead, 1977)

Steven Heller: Your book on Edward Gorey has been a long term journey for you. I know why I want to spend time reading it, but why did you want to invest so much of your life in Gorey’s head?

Mark Dery: Well, I doubt Jack Torrance imagined, when he entered the hedge maze at the Overlook Hotel, that he should’ve brought GPS! Meaning: I wanted to try the knobs on all the locked rooms in Gorey’s mind, but had no idea it would take seven-plus years. Then, too, at the risk of sounding defensive, it bears pointing out that seven years is a walk around the block for the average biographer. Ask Robert Caro. Most biographies take forever—and then some. A million little facts need to be nailed down, from the mundane—Was Gorey really awarded a medal for marksmanship in U.S. Army boot camp? (answer: yes)—to the profound: What, exactly, was the nature of his sexuality? In a sense, a biographer relives his subject’s life. Gorey had 75 years to live his; I only had seven. But the trickiest part of biographizing Gorey was his baleen-whale intellectual omnivorousness. It was only when I began exploring his head, as you put it, that I realized what I’d gotten myself into. He taught himself to read by age three, blew the fuses of every IQ test he ever took, seems to have had near-total recall of every ballet and movie he ever saw, and was impossibly eclectic and obscure in his interests, from 19th-century illustrators like Doré, Tenniel, and J. J. Grandville (whose engraving of a giant severed thumb he quoted in one of his books) to Asian philosophy (Taoism, Zen) to British book-jacket illustrators of the postwar period (Edward Bawden, Edward Ardizonne) to Ukiyo-e printmakers like Hokusai and Hiroshige to Irish writers like Samuel Beckett and Flann O’Brien to surrealism (Magritte, the collage novels of Max Ernst) to the silent films of Louis Feuillade to Balthus and Bacon and Star Trek novelizations (god help us!) and Golden Girls and ‘70s pop occultism (the Tarot, mostly) and the French avant-garde literary movement Oulipo to Jane Austen, Agatha Christie, Victorian true crime, Puritan primers, and, til death do us part, the ballets of George Balanchine. To map Gorey’s mind, I had to have at least a passing acquaintance with all those landmarks, it turned out. Then I realized it had to be better than passing, since Gorey’s art is informed by many of them; if I was going to analyze his work in depth, I needed to be able to detect references and allusions to his interests, and their influence as well.

SH: Gorey was a commercial artist working on the usual portfolio of material: book covers, editorial illustrations, book illustrations, and ultimately his own creations. He was, therefore, an artist, period. He was also a character, period. What from all these periods did you find was the most revelatory aspect of his life? Or was there some revelation in all aspects of his work?

MD: There are little revelations under the antimacassar or in that shadowed corner or in that disused dumbwaiter in everything Gorey did. I was fascinated to discover, for example, that his “silent” (meaning: wordless) book The West Wing, a book about restless specters and untenanted rooms in a haunted mansion that reminds us of the huge rambling manor in The Secret Garden and the possessed mansion in The Haunting of Hill House and the surrealist nocturnes of Louis Feuillade always had a second title, as Gorey told an interviewer: “The title the book does not have, but which is there in my mind, is The Book of What Is in the Other World”— a chapter in the Egyptian Book of the Dead detailing the sun god Re’s descent into the underworld through a portal in the far west and his travels in the kingdom of the dead during the night. Likewise, Gorey's postcard series, Q.R.V. Hikuptah, published four years before his death when he was staring his mortality in the face, has a secret chamber. Hikuptah, it turns out, is one of the ancient names for Egypt, meaning “mansion of the soul of the god Ptah,” the creator god of the ancient Egyptians and patron of craftsmen. As I note in the book, "Like Gorey, Ptah was bald and bearded; also like Gorey, he was closely associated with funerary rites and the afterworld.” These little Easter eggs are everywhere in Gorey’s work.

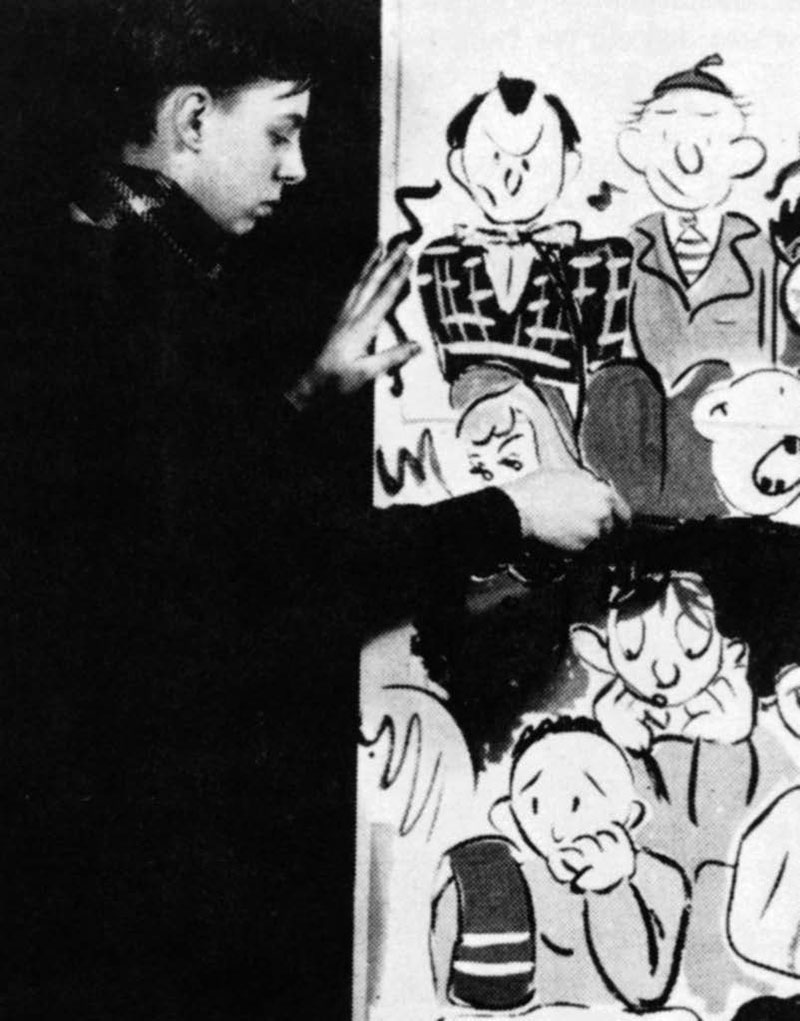

Gorey at work on a mural for a high-school social event, Parker Record Yearbook (1942). (Francis W. Parker School, Chicago.)

SH: A New York Times Style section article pegged to your book claims that Gorey is the pioneer of the macabre. How did he earn this distinction and why?

MD: He abhorred being typecast as the Grandaddy of Goth. When an interviewer observed, matter-of-factly, “You are a noted macabre, of sorts,” he said, “It sort of annoys me to be stuck with that. I don’t think that’s what I do exactly. I know I do it, but what I’m really doing is something else entirely. It just looks like I’m doing that.” Of course the lazy stereotype was adequately earned, to some degree: the funerary urns, the Dickensian gamines wasting away, the doomed mites assaulted by bears or run through by awls or sacrificed to Insect Gods. Obviously, he’s heavily indebted to Gothic novels and Victorian penny dreadfuls and late 19th-century mourning culture. But that’s just the aesthetic surface of what he’s up to. Underneath, he’s wrestling with all the big questions Beckett (whom he liked) wrestled with, though Gorey’s camp-macabre, ironic-gothic tone is lighter than Beckett’s mordant wit: the death of god, the meaning of life, the gnawing sense that the human comedy is a dark farce, and in nearly every book he wrote, the oncoming dark of our mortality. But he’s also using Puritan primers and Victorian sanctimony as an ironic language to parody the Wonderbread fatuity and Jesus-loves-me sanctimony of postwar America.

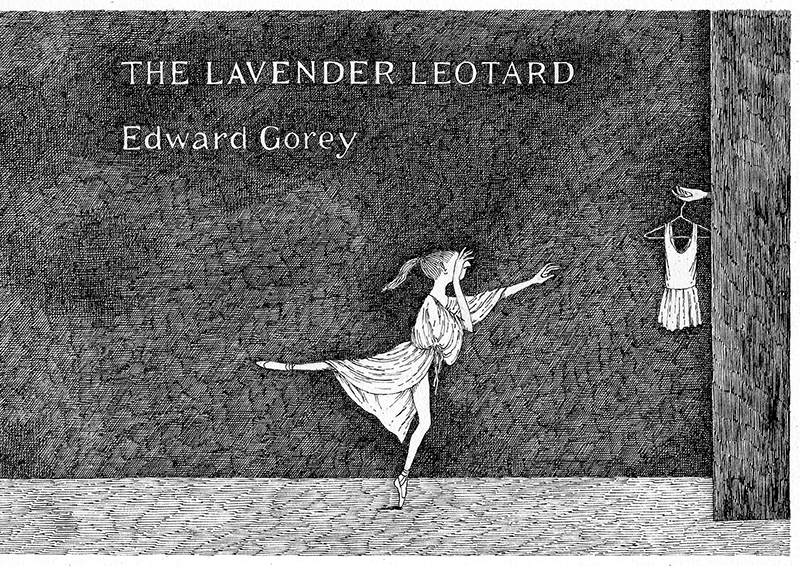

The Lavendar Leotard. (Gotham Book Mart, 1973)

SH: You are a master of language. I presume that there is a sympatico between your love and his inventive use of eccentric words?

MD: I’m blushing down to the roots of my rapidly receding hair. But yes, I do share Gorey’s logophilia—his love of obscure, arcane, and on some occasions sesquipedalian words like “sesquipedalian.” In Gorey’s case, that came partly from his inner antiquarian—remember, this is the guy who majored in French at Harvard because he claimed to have read everything in English from the 19th century—but also because he had the gene for logophilia: he exulted in the Times crossword, kept lists of juicy words he encountered in his peripatetic readings. Then, too, he cut his eyeteeth on books like Frankenstein and Dracula and the novels of Henry James, for lord’s sake, all of which he toiled through sometime between the ages of five and seven. So his vocabulary, like his draftsmanship, was deeply engraved with the sensibility of the late 19th century. As was mine, which is one of many reasons our minds chime. I grew up in Southern California in ‘60s and ‘70s but you’d never know it from my childhood reading. Most of the children’s classics I read were leftovers from that great efflorescence of children’s literature, the Victorian era, and shortly thereafter: Twain’s Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, which I re-read compulsively for years, Lewis Carroll’s Alice books, Wind in the Willows. I even read Booth Tarkington’s Penrod because I’d heard it was reminiscent of Tom Sawyer, an irretrievably weird thing to be doing in San Diego in 1966. Conan Doyle and Poe cast long gothic shadows across my childhood imagination. Like Gorey, I made lists of words that caught my fancy—the writer prepares!—and can still remember where I first heard certain words. “Putrescence,” for instance: I thrilled with horror at the last line of Poe’s “Case of M. Valdemar”—"Upon the bed, before that whole company, there lay a nearly liquid mass of loathsome — of detestable putrescence.” Delicious! The word, I mean, not the putrescence.

SH: If I recall, you never met him. What kind of spiritual hoodoo did you do to help channel him?

MD: I encountered him but didn’t meet him in any real sense. In 1983, when I was working as a lowly clerk at the legendary Gotham Book Mart, New York’s answer to Shakespeare and Company in Paris, Gorey came swanning in, beard rampant, amulets and necklaces clanking, radioactive-yellow dyed fur coat sweeping the floor, holding forth in the usual swooping, stentorian tones. Punk-rocker that I was—I was 23 and in the throes of my Patti Smith phase--I thought he was some insufferably pretentious old fop. Anyway, I can’t say I channeled him because there’s no getting inside Gorey’s head; it’s hermetically sealed. As I think I say in the book, he’s inscrutable because he refused to be scruted. I interviewed everyone on the planet who knew him, read every scrap of private correspondence and diary entries I could lay my hands on, and collaged them all together to make a Cubist portrait of the man, seen from every direction simultaneously. But I don’t pretend to know him, nor do I think anyone ever really did, including, perhaps, Gorey himself.

Gorey in his attic room at the Garvey's summer house in Barnstable, Cape Cod, 1961 (Photograph by Eleanor Garvey. Elizabeth Morton, private collection)

SH: What about reconstructing his life became the most pleasurable . . . and the most mysterious . . . and the most nightmarish?

MD: The most pleasurable: Being a fly on the wall during his Harvard cocktail parties with Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery. Prowling his Cape Cod home in Yarmouth Port, pawing through the oddments of a curiosity cabinet that was really a model of his unconscious. Reading his correspondence with his soul mate and collaborator on several children’s books, the writer and academic Peter Neumeyer. Talking to his impossibly WASP-y Cape Cod relatives about “Cousin Ted.” The most mysterious: dusting the crime scene of his secretive sexuality for fingerprints. Most nightmarish: his books. In a good way.

SH: I recall spending a brief time with him in both his Murray Hill brownstone apartment and Cape Cod home. The contrasts couldn’t be more profound . . . one dark and cluttered, the other light and minimal. How does this reflect his personality?

MD: Ever the Taoist, he rejoiced in binary oppositions.

SH: Again, knowing how long you worked on this, what aspect of Gorey’s life were you unable to pin down?

MD: The Freudian roots of his inscrutable sexuality—the buried memory that was the skeleton key to who he was.

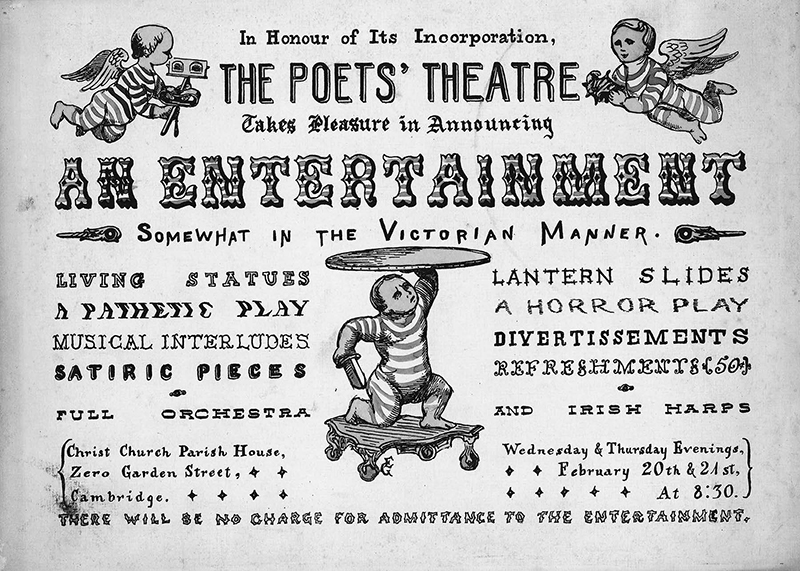

Edward Gorey, poster for 'An Entertainment Somewhat in the Victorian Manner' by the Poets' Theatre. (Larry Osgood, private Collection)

SH: What do you think your readers will take away from this book that cannot be found in any other account of his genius?

MD: There are no other Accounts of His Genius. Compared to this 500-page doorstop, they’re all Watchtower tracts! As for what readers will find in Born to Be Posthumous that they haven’t found in the odd magazine profile of Gorey, I trust in the oblique intelligence of Goreyphiles everywhere to find murder-mystery clues and Freudian subtexts in its pages that even I can’t imagine.