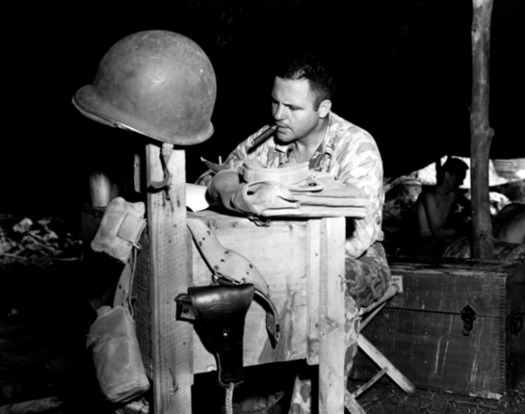

Col David Shoup, Chief of Staff, 2d MarDiv, Tinian, 1944. (Marine Corps photo)

I’m sure that everyone reading this post has, at one time or another, written a business memo that seemed especially inspired and cleverly effective. Well, be not proud; I happened to witness the most masterful memo ever written, a mere eight words that changed a culture instantly.

Far too long ago, I was a marine stationed on Parris Island, S.C., working as a combat correspondent (sans combat, to my great relief) under my benevolent commanding officer, Jim Lehrer. One of my assignments was to cover the arrival on the base of a new island commandant, a general named David Shoup. When he strode toward the welcoming party of top officers and NCOs, I noticed right away the pale blue, star-bedecked ribbon among the many decorations above the left-breast pocket of his uniform — the Medal of Honor. This highest award for valor was rarely seen on any living marine’s chest, but on a general it was an extraordinary sight. I knew from my reportorial research that Shoup had won his medal of honor at the vicious battle the 2nd Marine Division fought to take the Pacific Island of Tarawa. He was wounded several times, but refused evacuation in order to stay with his unit. Clearly, the general was a tough guy, and he looked it.

In those days, the cadre of drill instructors and training officers on the island had adopted a stylistic trademark of England’s Royal Marines, the swagger stick. This short, entirely useless wand of wood that was usually carried clamped under the left arm. As with everything else in the military, rank had its privileges. The bottom of the NCO rung carried bamboo sticks, while majors and above carried ebony sticks with silver caps. All sorts of gestures were made with the swagger sticks, including the rhythmic slapping of the thigh indicating that a drill instructor was not happy with the “maggots” he was charged with turning into marines. Occasionally, some of the higher ranking officers would acknowledge salutes by touching their swagger sticks to the visors of their uniform caps, a mannerism strictly not by the book.

After noticing the Medal of Honor ribbon on the general’s uniform, I noticed that he did not carry a swagger stick. Almost all of the officers in the greeting committee did, however, though none dared salute with it. Did I notice a stony stare for the new commander? I did not, but now I can well imagine there may have been one.

Shoup was what was known as Old Corps, a no-frills traditionalist who would, a few years later, become Commandant of the Marine Corps, promoted to the top job by President Eisenhower over several more senior generals. Within a week of his arrival on Parris Island, a memo “From the Commanding General to All Personnel” was posted throughout the base:

Regarding swagger sticks: If you need one, carry one.

The next day, the Freudian subtext of those few words having been heard loud and clear, there was not a swagger stick to be seen. When I returned to the island many years later, as a civilian journalist, the affectation had not returned. And I have never quite forgotten what that memo taught me: When you can give an order without actually giving an order, you’ve quietly but emphatically shown who’s the boss.