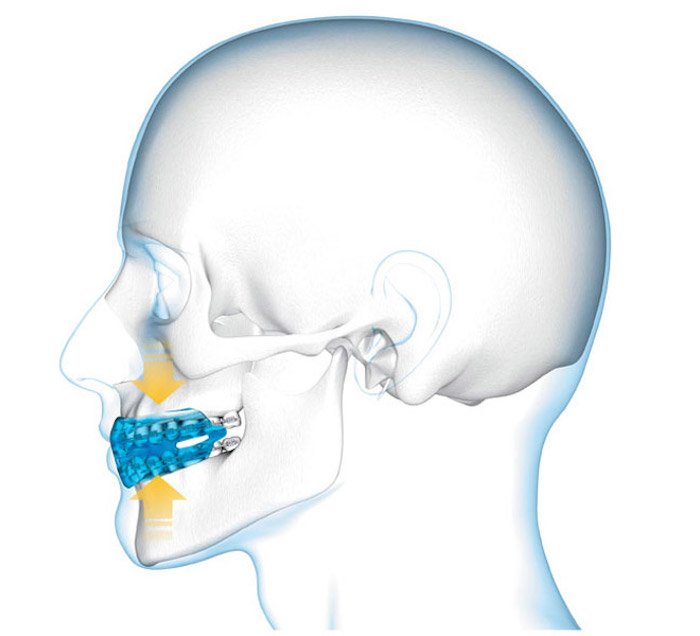

Our teeth need a safety belt. At present, 33 million adults in the United States annually report grinding their teeth. A nocturnal habit once thought to affect only “women married to docile and passive men,” harried schoolteachers, maladroit children, or “people who do precise work like watch makers,” bruxism is a thoroughly mainstream malady, increasing thirty percent since the onset of the Great Recession in 2007. To prevent people from pulverizing their teeth, gums, and jawbones, dentists recommend a seemingly obvious stress-relieving agent: mouth guards. The simplicity of this product masks a motley design history, however, culled from extreme examples of the human body under stress.

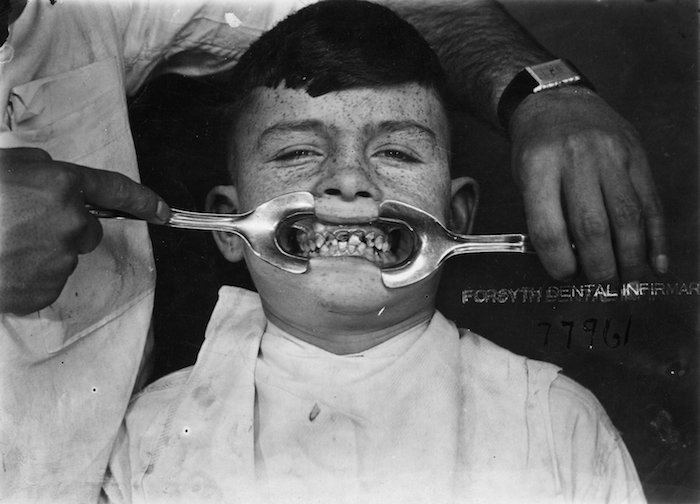

Mouth guards were first forged in the boxing ring. Between 1890 and 1892 British dentist Woolf Krause designed one of the earliest recorded mouth guards for professional boxers, who frequently suffered punishing dental injuries that forced them to forfeit matches. Krause’s mouth guard was a vast improvement over the plugs of wood, wadded paper, and tape that boxers employed in feeble attempts to save their teeth from punches and related strain. Yet his contrivance remained far from ideal. Cut from foul-tasting gutta percha (a tree-based rubber also used to insulate telephone cables and fill root canals), Krause’s design required boxers to clench their teeth continuously to keep the guard in place, hampering their attention in the ring.

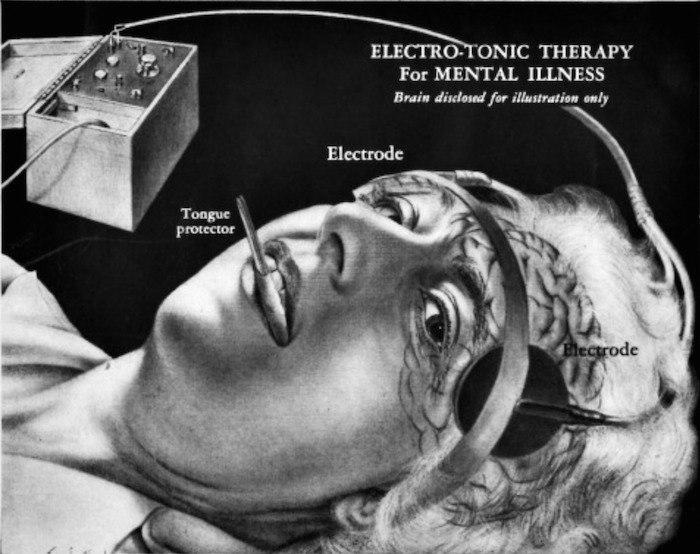

Boxers were not alone in sacrificing their teeth for mouth guards. Schizophrenics and depressives served as guinea pigs, too, under the auspices Robert E. McClure, an inventive dentist at the sprawling Mayview State Hospital a few miles south of Pittsburgh. Realizing in the late 1960s that electroconvulsive therapy caused patients to clench, crack, and even swallow broken teeth (or bite through their tongues) McClure committed himself to designing an appropriate mouth guard.

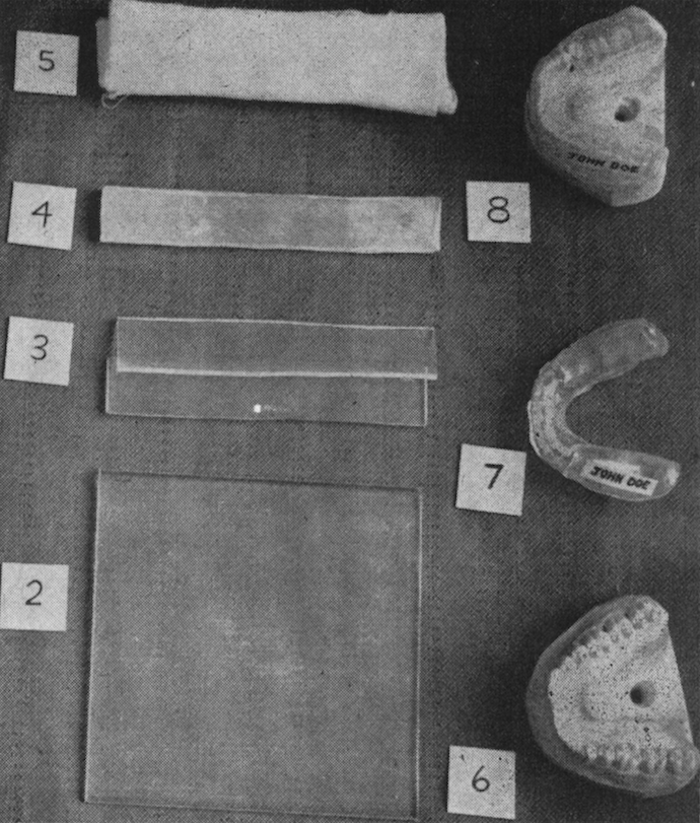

His solution? A square of “dental plastic” molded from a versatile new compound, ethylene-vinyl acetate, first patented in the US by the DuPont Corporation in 1956. Lightweight, strong, and water resistant, McClure’s mouth guard more than withstood the two hundred-plus pounds of pressure his patients exerted upon their teeth when they clenched together during electroconvulsive therapy. Even better, McClure’s mouth guard was reusable. According to the dentist, a single inexpensive sheet of dental plastic could be heated repeatedly to custom fit the teeth of up to 242 psychiatric patients before needing to be replaced.

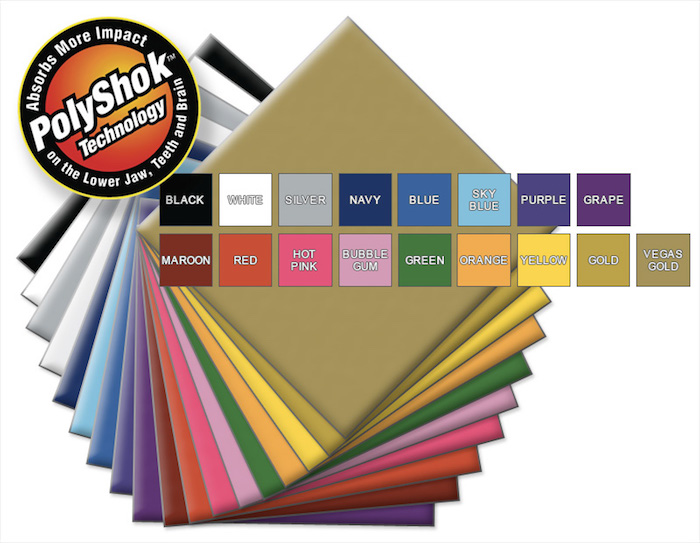

Devised to prevent injuries among a unique population, McClure’s design now informs every part of the $81 million mouth guard industry. For the forty million guards sold annually in the US manufacturers have tweaked McClure’s ethylene-vinyl acetate into a copolymer called PolyShok. First used for rubber bullets, this comfortably thin, shock-absorbent plastic comes in a pleasing array of colors including “bubble gum” and “Vegas gold.” Like McClure’s design, contemporary PolyShok mouth guards also boast an appealing price tag, running anywhere from $17 to $33. (Indeed, only two to four percent of adults who grind their teeth ask dentists to cut more precise guards, which cost upwards of $1,500.)

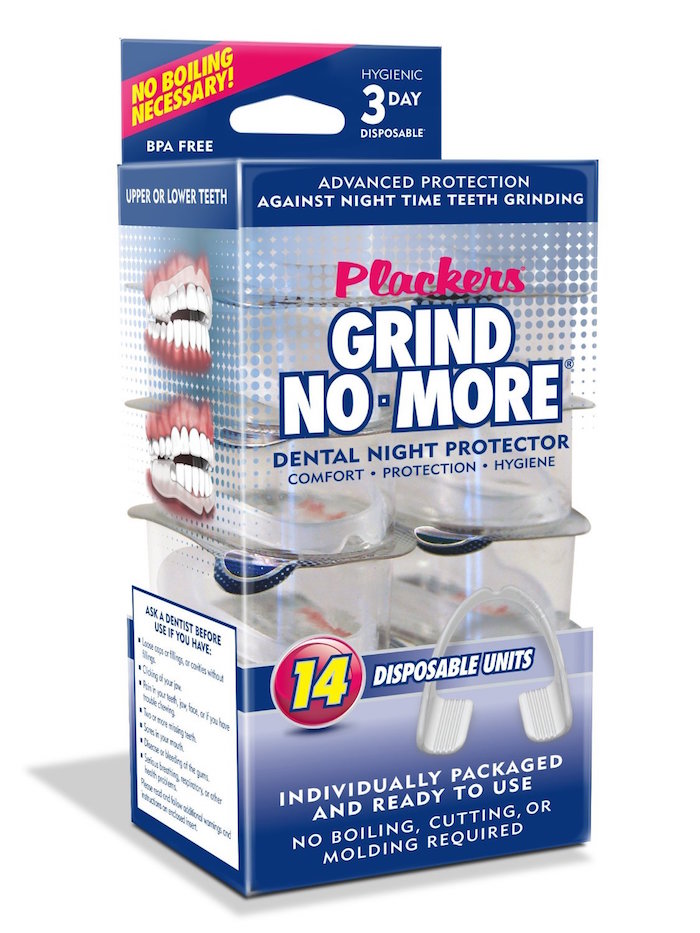

McClure’s reusable design also encouraged the widespread manufacture of easily customizable “boil and bite” guards. Consumers can adjust the fit of these products by soaking them in scalding water and then sinking their teeth into the softened plastic as it cools, resulting in a progressively aligned guard that keeps teeth from gnashing against one another at night.

A remarkable design achievement, mouth guards are nonetheless grim little items. Sales have risen seventy-seven percent from 2010 to 2014, suggesting that stress levels once provoked by extraordinary circumstances—boxing, intense psychiatric treatment—have crept into the everyday lives of “highly determined people,” as The Washington Post obliquely observed in 2015. For millions of Americans struggling against financial uncertainty, familial pressure, or unpredictable work, mouth guards may ultimately offer only temporary relief. Under habitual psychological strain human teeth and jaws can exert a grinding force greater than that of a gorilla, and not a single mouth guard on the market guarantees that it can withstand being bitten in two.