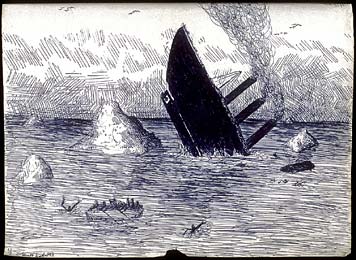

Michael Bierut, illustration for sixth grade social studies report, "Disaster at Sea: The RMS Titanic," 1968

I was in the first grade when I made the discovery that changed my life. We were given a reading assignment that involved drawing something in the room that began with the letter F. I drew a flag that stood in the corner of the classroom. I still remember the drawing: the flag, complete with folds, the stand with its five-prong base, the storage closet next to it, the window on the other side, and the trees and portions of rooftops outside the window. I didn't think there was anything particularly special about it. But my teacher, Mrs. Kinola, sent it home with a note: It looks like Mike is quite an artist!

That single sentence established the defining characteristic of my childhood. I got good grades, but so did a lot of people. You could get good grades by studying hard, something that many of my peers, especially the boys, felt reflected a misguided attitude about priorities. I seemed to have no real talents. I couldn't throw or catch a baseball with authority, punch someone in the face, or shoplift. But now I had something I could call my very own. I was good at art.

At St. Theresa's School in Garfield Heights, Ohio, in the early sixties, being good at art enjoyed a special status. It wasn't just a skill, it was a God-Given Talent. I made the most of it. I was shy and socially inept, but now I had something with which to gain purchase in elementary school society. My interest in art was encouraged by my parents, who bought me progressively more exotic tools: pastels, watercolors, charcoal pencils. These alone made useful conversation starters in the lunchroom, but I always made it a point to have some of my most recent work casually available for review. As my skill increased, so did the predictability of the response I got. It took the form of a single question, almost always phrased the same curious way: "Did you draw that freehand?"

Of course, that was the trick. What was admired wasn't the artistic impulse — this was something that to this day I'm not sure I actually possess — but something else: the ability to do realistic drawings, the more photographically representational the better. By this standard, the highest possible compliment was "C'mon, you fuckin' traced that!" And naturally, the more painstaking the detail, the more time-consuming the execution method, the greater the acclaim I received. Despite my growing fame as an artist, I had no social life. Thankfully, this permitted me to turn my undivided attention to epic six-hour sessions of crosshatching, creating work as awe-inspiring to my fellow sixth-graders as a magic trick.

Being the local go-to guy for art had another advantage: it permitted me to cut across the schoolyard's Byzantine clique structure. I made posters for the drama club, banners for the football team, campaign buttons for the student council candidates. And with acquisition of a Speedball lettering pen set in junior high, the last piece fell into place. Once it was learned I was a fellow who could bang out a convincing Fraktur my popularity soared among the the school's hard core fans of Judas Priest and Black Sabbath.

It goes without saying that my God-given talents usefully augmented my academic ambitions as well. I never turned in a report or term paper without an elaborate cover and a lengthy appendix filled with predictably overwrought drawings of the subject at hand, whether it was unicellular flagellates, the buildings of Washington, D.C., or the sinking of the Titanic. Was it unfair that my grade often went up a notch because of these elaborate but usually irrelevant embellishments? Sure. But it was also a useful lesson on the relationship of form and content.

In fact, when I look back today, I can see a clear pattern. My eagerness to please, my enthusiasm about working with as many different groups as possible, my discovery that a good-looking package could improve the impression made by its contents: these are all traits that led me not into art, but into graphic design. Today my clients are usually more sophisticated than those Black Sabbath fans in eighth grade study hall; the content I work with hopefully has more substance than my landmark opus from 1968, "Disaster at Sea: The RMS Titanic." But the process, and the impulse that motivates it, has been much the same for the last 40 years.

I wonder if I would have made the same discovery about myself if I'd been born 40 years later. A few weeks ago, I went to my daughter Martha's middle school science fair. In my day, this would have been an excuse to unleash every gimmick at my disposal, mounting an orgiastic display of three-dimensional lettering techniques, full-color diagrams, and impeccably rendered views of...well, whatever. Hamsters, nuclear reactors, the inner ear, the solar system. Who cares? No matter that very little actual science would be on offer. I would still get crowds and spend the evening answering the same question over and over: yes, I did draw it all freehand.

Today, affluent kids enjoy nearly universal access to programs like Photoshop and Powerpoint. So everywhere I looked I saw lettering and images that would have put my handcrafted efforts to shame. In some ways, it was inspiring. The tools of graphic design, even manipulated by seventh and eighth graders, brought the content to the foreground in every instance. It was easy to see who was good at science. But it was hard to see who was good at art.