The Design Observer Twenty | Sponsored by IDEO

The Design Observer Twenty is our curated selection of twenty remarkable people, projects, and big ideas solving an urgent social need.

Reddy leads the company’s formal philanthropy efforts, oversees an additional $50 million in corporate contributions, supports employee engagement with the community, and helped launch a $1 billion impact investing portfolio that seeks both financial and social returns. “We’ve seen some things. And we’ve learned a lot.”

They’re also deeply entwined in the modern history of civil rights. “We went through the crucible of Newark,” says Reddy, referring to civil unrest that erupted in the company’s hometown in 1967. “It remains an important part of how we think.”

While violent protests roiled many cities across the U.S. that summer, Newark’s was the deadliest. The riots lasted four days, fueled by unaddressed poverty, police violence, and the unyielding white political power structures. Prudential stayed and helped communities rebuild. “There’s a beautiful quote from a former poet laureate, ‘Our Newark wears the scars of Western democracy on her face,’’’ says Reddy. The relationship they’ve built with the city, which she calls an expression of shared value, is about showing up, building trust, and staying proximate to the people doing the work. “It gave us a lens of racial equity before it was called that.” The company has invested over $1.2 billion in the city over the past decade alone; most recently the $500K Prudential Community Grants project, launched in March to support local, community-based projects.

More recently, an incident from their past offered an opportunity to dig deep again.

A groundbreaking 2019 PBS documentary called Boss: The Black Experience in Business cited a forgotten episode in Prudential’s history. “Scientific” research published by a Prudential employee in 1896 called “Race Traits of the American Negro” used racist assumptions about the “fitness” of African Americans to predict that the Black race would eventually become extinct. It led Prudential to stop insuring Black customers, and other companies followed suit. While the event catalyzed an emerging Black-owned insurance industry, years later, the revelation upset plenty of Prudential employees, particularly Black ones.“It was upsetting but not shocking,” says Reddy, a former civil rights attorney. But as the pandemic took hold and the murder of George Floyd forced broader discussions about racial disparities in society and in the lives of Prudential employees, the documentary seemed like an opportunity to address the pain employees were feeling, and go deeper into the work they had already been doing. “You can’t move forward until you address the past.”

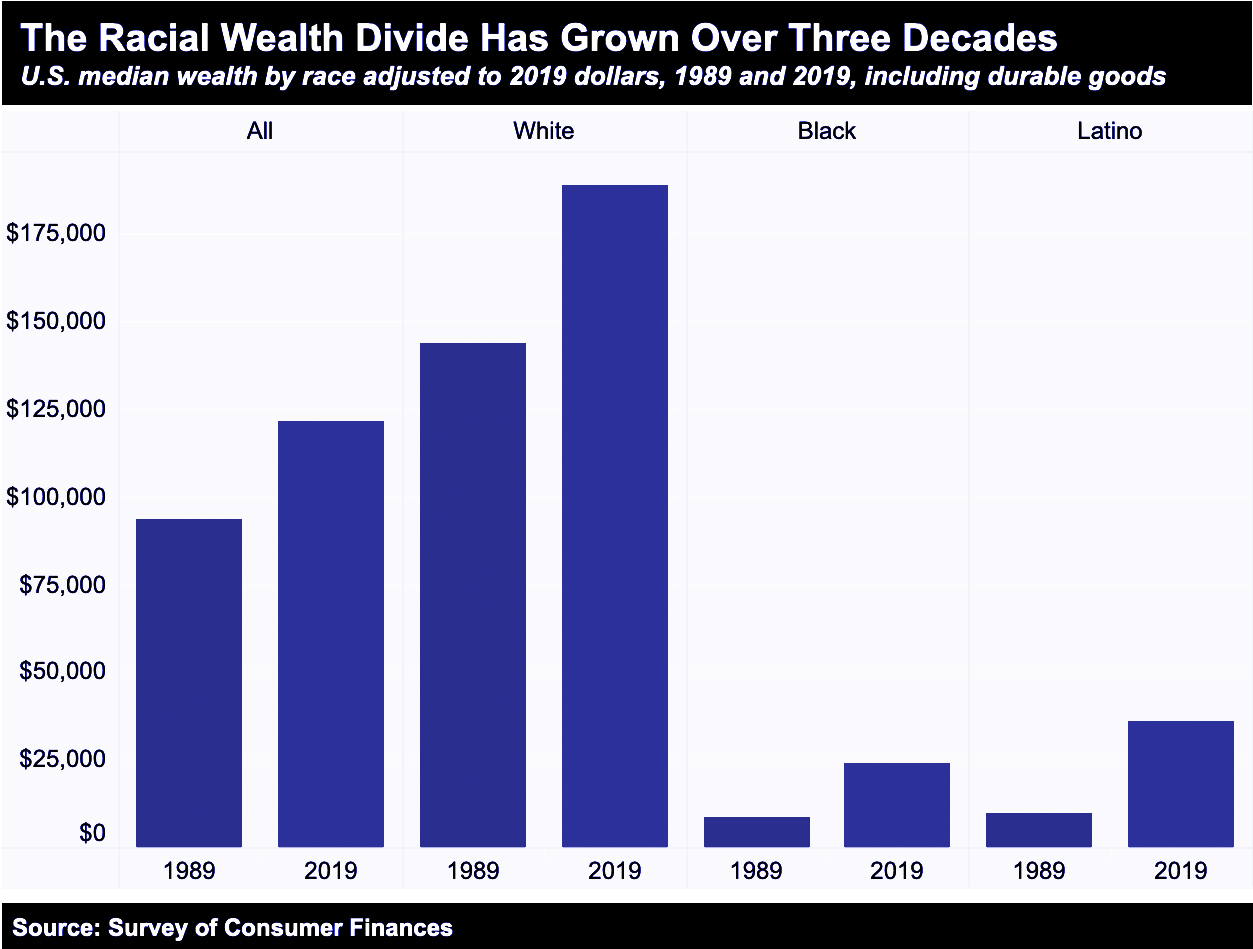

Supported by Prudential’s leadership team, more than 1,000 employees dialed in to a candid call, led by a historian, to talk about the company’s ugly past. Soon, a new, multi-department initiative found its way to the drawing board, one that would more directly address a legacy of financial disparity with new products and useful information co-created with Black leaders, and designed to help Black families build generational wealth wherever they were in life. The new initiative, Blueprints to Black Wealth, three years in development, began rolling out this August.

You shouldn’t be afraid of looking at your past. You should be more afraid of not looking at it.

Lata Reddy

“It’s not just about people we can sell to, it’s about understanding where the barriers are for people to get the information they need,” Reddy says. That means working with an array of expert partners and co-designing with people who are already serving Black communities, like the dfree Foundation in Newark, the Metro-Detroit Black Business Alliance in Detroit, and the Atlanta Wealth Building Initiative.

Inclusive products and markets are good business, says Reddy. But the work to get there can be challenging. “It takes time and courage, but this is something everyone can do,” she says. “There’s always a chance to examine deeply how the institution you represent has contributed to today’s injustices, and to understand how you can be part of systemic solutions now.”

Essay by Ellen McGirt.