The Design Observer Twenty | Sponsored by IDEO

The Design Observer Twenty is our curated selection of twenty remarkable people, projects, and big ideas solving an urgent social need.

As a theoretical cosmologist and particle physicist, Chanda Prescod-Weinstein spends her time looking up — though that’s often metaphorical these days. As an associate professor of physics and core faculty member in the Women and Gender Studies department at the University of New Hampshire, she works with graduate and post-doctoral researchers, collaborates with colleagues, and contributes to a steady stream of professional commitments, including a seat on the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine committee tasked with understanding the societal benefits of particle physics research.

But even with her head down, she’s thinking about the universe.

“I think about the fundamental questions relating to the origin of space, time, and everything inside it,” she says. “I think about dark energy. I think about the structure of neutron stars,” and all the invisible stuff obscured by the luminous stars we think of as defining the cosmos. To look at the night sky is to miss the big picture, she says; the invisible stuff vastly outnumbers the visible elements that the Standard Model of particle physics describes. As she explained in her astonishing 2022 TED talk, “Visible matter, the kind we and the stars are made from, the kind that radiates light, is not what’s normal. We … are the cosmic weirdos.”

The Milky Way. CC0 Public Domain Image: Andrea Stöckel

Prescod-Weinstein also brings a tireless energy to her calls to make systemic racism in academia, science, and society visible to all, deftly mixing race, gender, and the cosmos in everything she does.

In 2021, she published The Disordered Cosmos: A Journey into Dark Matter, Spacetime, & Dreams Deferred. It’s a wide-ranging, geeky, and deeply personal book, worthy of a queer, Black, Jewish kid from a working-class neighborhood in East Los Angeles: partly the glory of discovery, and partly her journey through legacy systems designed to exclude.

“The Standard Model of particle physics is also all the things that a Black child is made out of,” she writes. But a homogeneous, white scientific community is not equipped to see anything but its own world view. “Part of science, therefore, involves writing a dominant group’s social politics into the building blocks of a universe that exists far beyond and with little reference to our small planet and the apes that are responsible for melting the polar ice caps.”

Without true diversity, physics will remain tied to the legacy of nuclear weapons and the quest for global power. “I believe we can keep what feels wondrous about the search for a mathematical description of the universe while disconnecting this work from its historical place in the hands of violently colonial nation-states,” she writes.

Her views led her to co-found (with many others) Particles for Justice, a multiracial, multiethnic, gender diverse, multinational, queer, and straight group of physicists to address, among other things, the legislative restrictions on African American, women’s, and gender studies in education.

To look up is to miss another, more pressing big picture, Prescod-Weinstein says. She points out that access to the sky is also a social and economic problem.

“Someone tweeted at me that for most of their lives, they didn’t know that the Milky Way was visible,” she says. “I certainly didn’t grow up seeing it in Los Angeles.” She thinks about the ancestors who knew the night sky and finds it bizarre that we cannot not experience the same awe. That same starry night has inspired centuries of art, science, literature, philosophy, and faith.

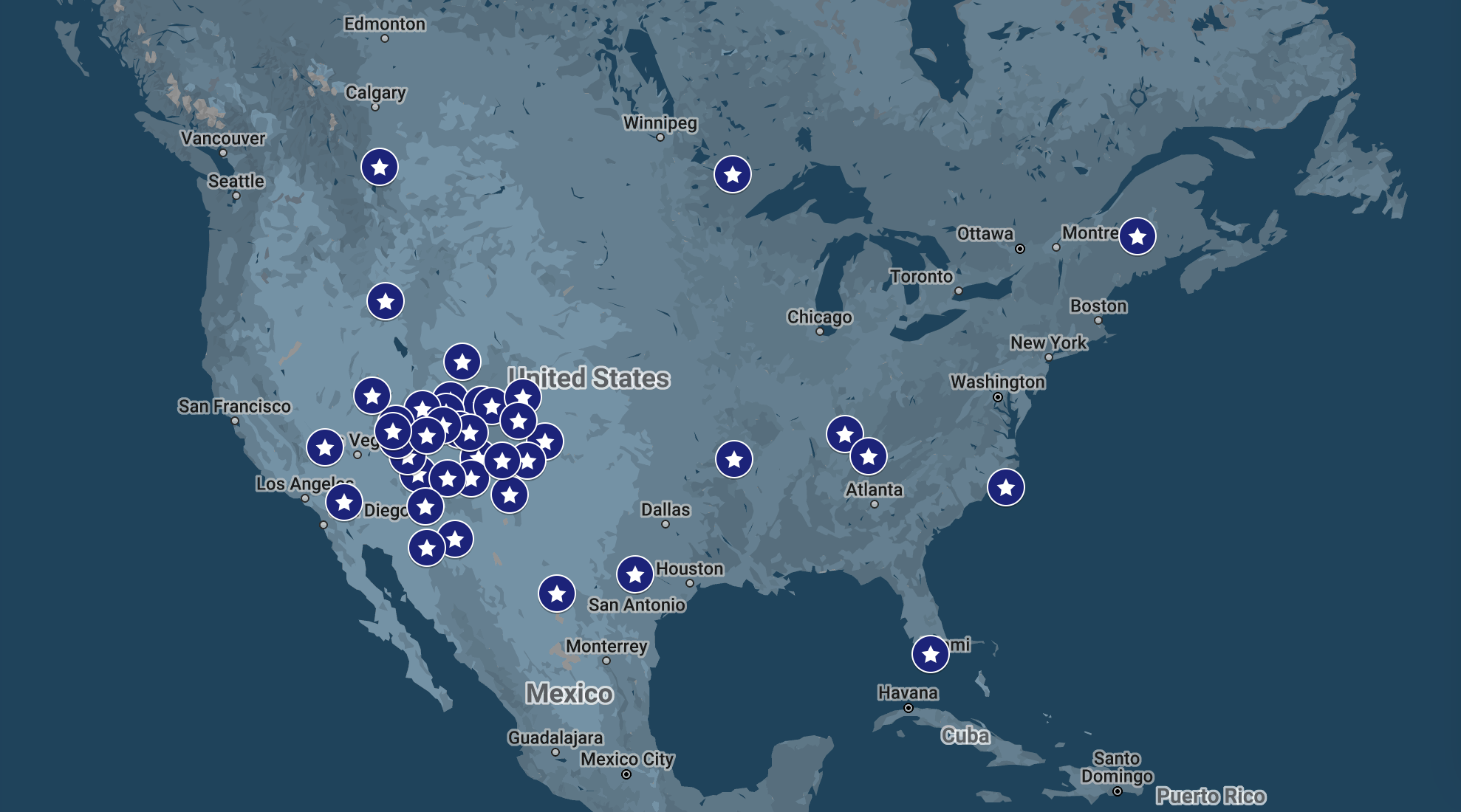

A map of dark parks

Light pollution wastes energy, interrupts natural migration patterns, and is bad for human health. And we do it to ourselves: The dark is drowned out by the streetlights of white-flight suburbs and college campuses, and by smog in industrial areas. It’s also by design. Incarcerated people are rarely permitted to experience the dark sky, nor can third-shift workers. “I can see the stars here in coastal New Hampshire, but only because I don’t have mobility issues and can walk on the beach.” You don’t have to be religious to understand our spiritual heritage is at stake. “Check out the International Dark Sky Organization — they’re doing really important work.”

Seeing the stars may not guarantee a path to poetry or physics, but it might be the best opportunity to contemplate true complexity.

“It’s a chance to think about: ‘What is this universe that I live in?’” she says. “Everyone has a right to know the universe.”

Essay by Ellen McGirt.