I. What is the Land Grant Act?

- Commemorating the centennial of land grant colleges and state universities, President John F. Kennedy gave the following address:

- “In July 1862, in the darkest days of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln signed two acts which were to help mold the future of the Nation which he was then struggling to preserve. The first of these, the Homestead Act, provided ... ‘a farm free to any man who wanted to put a plow into unbroken sod.’ The second, the Morrill Act, donated more than one million acres of Federal land to endow at least one university in every State of the Union.”

- “These schools,” Kennedy added, "are one of the finest examples of our Federal system: the fruitful cooperation between National and State Governments in the pursuit of a decent education for all of our citizens.”

- When Kennedy spoke these words, Virginia’s “senior” land grant university “was nominally all male.”

- “And though the institute had admitted its first black student in 1953, it remained overwhelmingly white.”

- A fact that remains true today.

- So what does a decent education for all of our citizens really mean?

- And how do we reconcile over 150 years of public funds, subsidized by the many, to advantage the few?

- Let’s start by defining the Land Grant College Act. What was it?

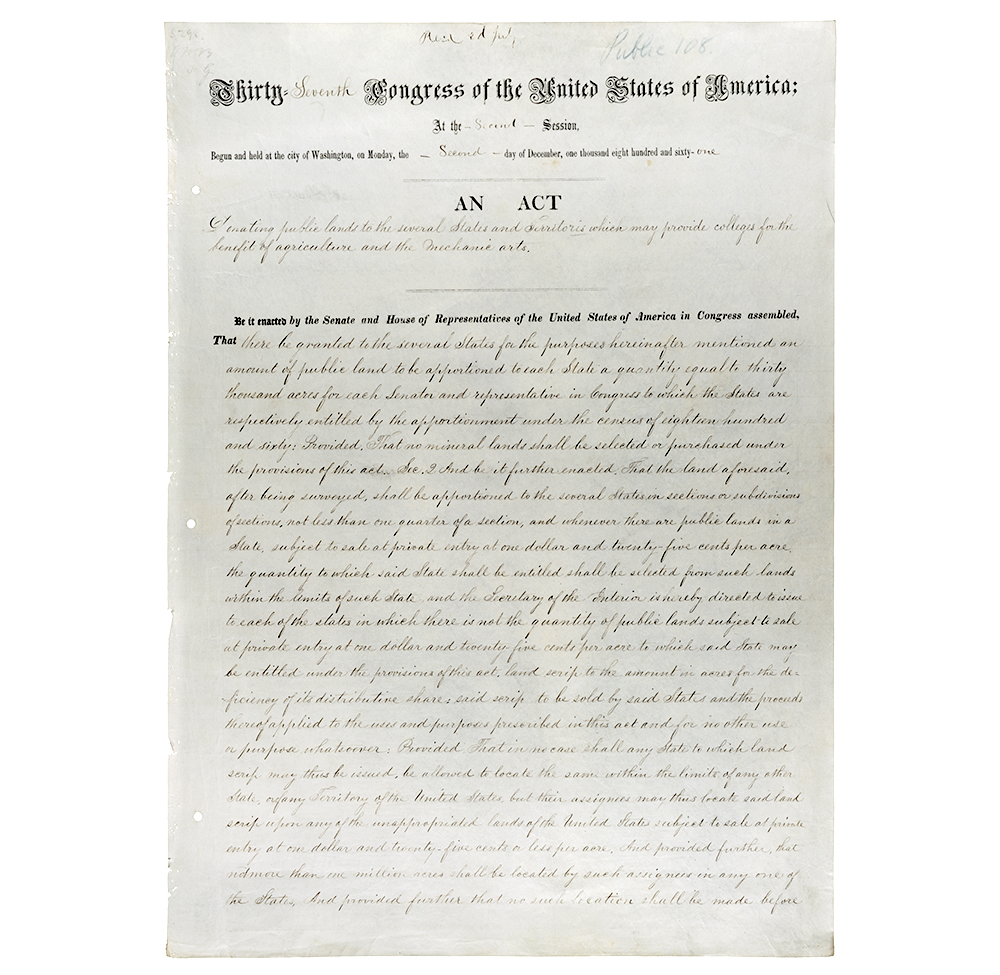

- “The Morrill Land-Grant College Act of 1862, also called the Morrill Act ... made public land available to states to sell, with the profits going toward establishing and supporting public colleges and universities.”

- This act allowed for the “foundation of a state university [system] for the agricultural and general industrial classes” to establish “the most comprehensive system of scientific, technical, and practical higher education the world has ever known.”

- Such a federal approach to education was novel — a concept often attributed to Illinois educator Jonathan Baldwin Turner.

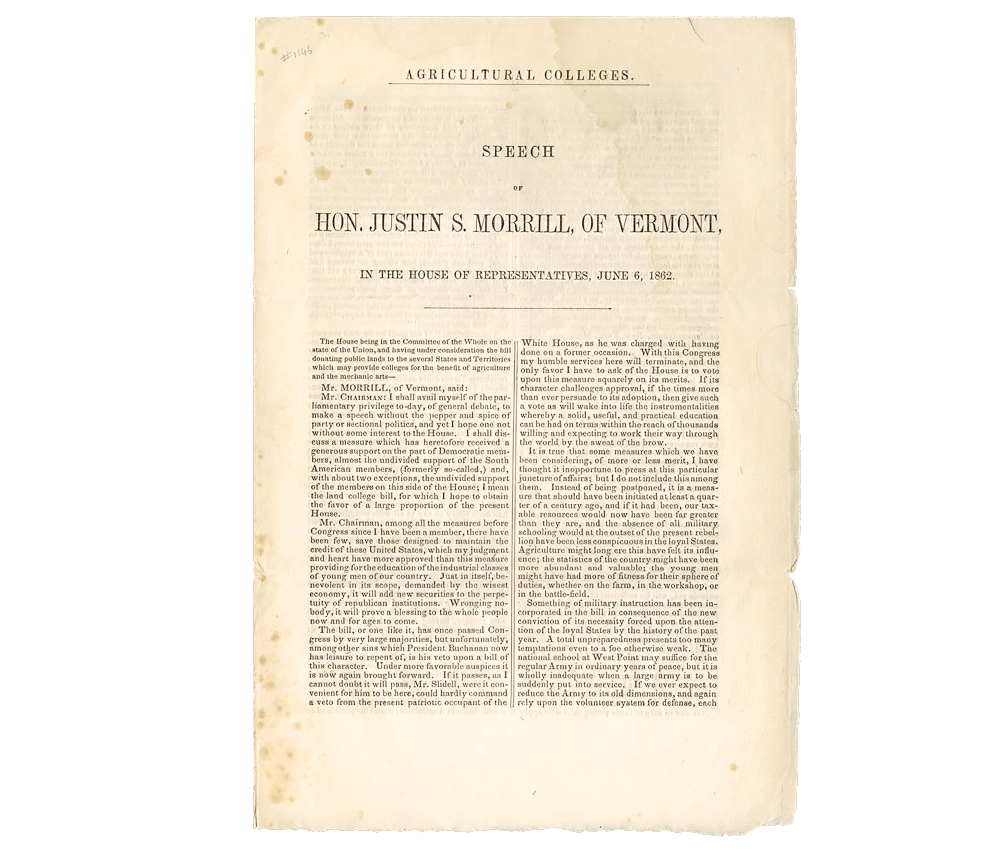

- But it was Justin Smith Morrill, a congressman from Vermont, who championed this vision in Congress.

- Interestingly enough, Morrill proposed the bill not once but twice. First in 1857, where it was passed by both houses, but vetoed by President James Buchanan. And second in 1861, where it was finally “signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on July 2, 1862.”

- Keep in mind that this act was signed during the Civil War — a context which influenced both the designing and signing of the legislation.

- The details of the act are as follows:

- “20,000 acres of federal land were to be apportioned to each state for each senator and representative serving in Congress. The land’s value was established at $1.25 per acre. In the event there were not sufficient public lands in a state, then the government issued scrip representing land in an unsettled portion of the country to that state. The proceeds from the sale of the land or scrip must be invested in safe stock yielding no less than 5%. The invested money would constitute a perpetual fund to support at least one college per state that offered courses in agriculture and mechanical arts.”

- In other words, proceeds from land grants created a fund for educating the industrial class — not the elite — with a goal of “producing better farmers” for “higher cultivation” of the soil.

- Overall, in providing accessible, practical education in each state, the Morrill Act is often revered as “democratizing higher education”.

Agricultural Colleges. Speech of Honorable Justin S. Morrill in the House of Representatives, June 6, 1862. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

II. Common Misperceptions

- Yes, the Land Grant Act democratized higher education, indeed, but it can also be seen through another, more critical lens:

- “As important as land-grant colleges were and continue to be, they must also be seen as part of the process of settler colonialism. The land-grant colleges were both founded on appropriated land and funded by the sale of appropriated land and, therefore, encouraged westward migration and settlement. The college boosters emphasized agricultural and scientific education that would help foster capitalism, industrialization, and nation-state building.”

- Even more so, this university system may be “part of a bigger project of establishing international strength...” and “as a means to expand the economic and political influence of the United States.”

- To better understand this perspective, let’s address three common misperceptions about the Act:

- The first: The grant uses public lands.

No, “The Morrill Act turned Indigenous land” — not public land — “into college endowments”. This was land and that had been seized or “expropriated from tribal nations”. - The second: The land was meant to establish campuses.

No, this land was meant to sell — to provide an original endowment to the college. Some confound the word “land” with farming, as these were intended to be agricultural colleges, but the original grant was for the sale of land or a land scrip. - The third: The grant was a one-time deal.

Actually, these are original university endowments and the “money made from land sales must be used in perpetuity, meaning those funds still remain on university ledgers to this day.” - And so, these grants have been called “the gift that keeps on giving.”

- Overall, the federal government bestowed land to states, that had been seized or dispossessed, in order to sell at a profit. This created an original, permanent endowment for schools.

- There’s an excellent article by Robert Lee and Tristan Ahtone called “Land-grab universities” that explains how, tragically, our public education system is built on appropriated Native American land.

- Here’s the irony: As we just read, Kennedy praised Lincoln, The Homestead Act, and The Morrill Act in national celebration.

- Yet a few years later, Dr. Martin Luther King referenced the same history, in solemn reflection.

- “In 1863 the Negro was told that he was free as a result of the Emancipation Proclamation being signed by Abraham Lincoln. But he was not given any land to make that freedom meaningful. It was something like keeping a person in prison for a number of years and suddenly discovering that that person is not guilty of the crime for which he was convicted. And you just go up to him and say, ‘Now you are free,’ but you don’t give him any bus fare to get to town. You don’t give him any money to get some clothes to put on his back or to get on his feet again in life ….

- “And the irony of it all is that at the same time the nation failed to do anything for the black man, though an act of Congress was giving away millions of acres of land in the West and the Midwest. Which meant that it was willing to undergird its white peasants from Europe with an economic floor.

- “But not only did it give the land, it built land-grant colleges to teach them how to farm. Not only that, it provided county agents to further their expertise in farming; not only that, as the years unfolded it provided low interest rates so that they could mechanize their farms. And to this day thousands of these very persons are receiving millions of dollars in federal subsidies every year not to farm.

- “And these are so often the very people who tell Negroes that they must lift themselves by their own bootstraps. It’s all right to tell a man to lift himself by his own bootstraps, but it is a cruel jest to say to a bootless man that he ought to lift himself by his own bootstraps.

- “We must come to see that the roots of racism are very deep in our country, and there must be something positive and massive in order to get rid of all the effects of racism and the tragedies of racial injustice.”

- This was King’s last sermon before he was assassinated.

- It is an unanswered call and response.

- So what is this positive and massive change? Could it be found in the Land Grant mission itself?

Act of July 2, 1862 (Morrill Act), Public Law 37-108, which established land grant colleges, 07/02/1862; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789-1996; Record Group 11; General Records of the United States Government; National Archives

IV. The Land-Grant Mission

- Design programs are often situated at land grant institutions. And since “history is literally present in all that we do” it’s important for designers to understand the historic context. So if you’ve ever attended a Land Grant university, or worked at one, you’ll be familiar with its “three-fold mission” of research, teaching and extension. I’ve taught at three, and the message is consistent across schools. But when did this start?

- As you probably guessed, the language is found in the original Morrill Act, and further grounded by three key acts that followed — that deserve our attention. [Get ready to memorize.]

- They include:

1887: The Hatch Act (research)

1890: The Second Morrill Act (teaching, et al.)

1914: The Smith-Lever Act (extension) - After the Morrill Act of 1862, several states “found it difficult to appropriate sufficient funds to continue to operate” their land grant schools.

- So the federal government acted. Quite literally. The government offered more funding through a series of acts, often matched by the state, to provide annual support.

- So when I say ACTS, you think ACT$, got it?

- Here’s a synopsis:

- The Hatch Act established the “agricultural experiment station program”. This is yearly funding, matched by the state, for agricultural research.

- The Second Morrill Act of 1890 “provided for annual appropriations to each state to support its land grant college.”

- This is a significant act because it also ... “forbade racial discrimination in admissions policies for colleges receiving these federal funds.”

- Yet...

- “A state could escape this provision ... if separate institutions were maintained and the funds divided in a “just,” but not necessarily equal, manner. Thus the 1890 act led to the establishment of land grant institutions for African Americans.”

- Virginia Tech, for example, receives two-thirds of the annual appropriation. [We’ll talk more about this later.]

- And finally, The Smith-Lever Act established the Cooperative Extension System and field demonstrations. Again, this was yearly funding, matched by the state, for community education.

- We’ll stop there. But it doesn’t stop there. Over the years, there have been numerous ACT$ (~13 notable ones) to further support land grant universities (or increase membership). You can see all 112 schools on this great map.

- Overall, “the land-grant university system has continued to evolve through federal legislation. The federal government provides funds, often with state matching requirements, to execute the system’s three-fold mission of agricultural teaching, research, and extension.”

- Is that all we have to learn?

- No, there’s more!

- Along with the three-fold mission, there was a three-fold educational agenda that’s important to note.

- Learning agriculture, mechanical arts and military tactics — were all part of the original vision.

- And here’s a critical consideration: these disciplines have been, and still are, male-dominated (amongst faculty, students and administrators alike).

- So in 2018, when the “Virginia Cooperative Extension and the Virginia Agricultural Experiment Station received $168,313,960 from federal, state, and local government, as well as from grants, contracts, and other sources” — who are the primary beneficiaries?

- Is it a diverse lot?

- This is around $100 million in public funding, mind you. For just one land-grant school. For just one year. And for whom?

- Overall, who are the primary recipients of immense, annual public research funds and academic appropriations, and do they reflect state demographics? If not, what policy changes can be made — at federal, state and school levels — to better serve the community that pays into the system?

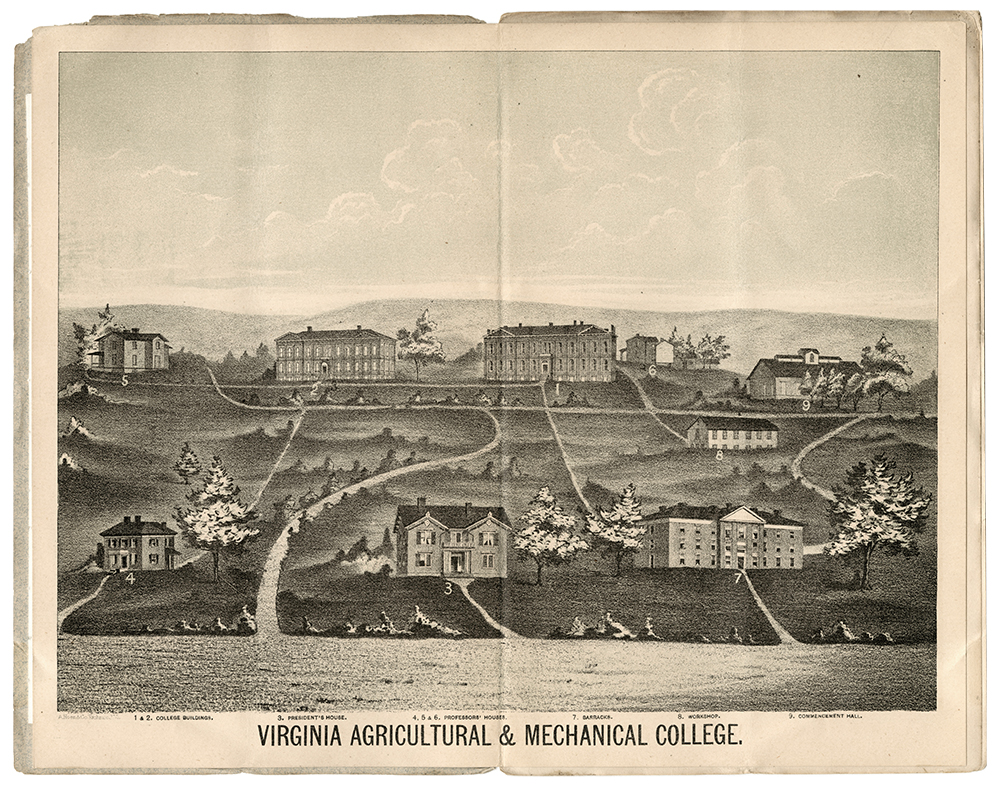

Campus map spread (above), cover and typographic detail: Catalogue of the Virginia Agricultural & Mechanical College, Session 1883-84, Special Collections and University Archives, University Libraries, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

V. Case Study — Virginia Tech, Virginia’s “senior” land grant university

- After the Civil War, “Virginia was readmitted to the Union in January 1870” and able to apply for Morrill Act land grants — to establish its land-grant college.

- As such, “Under the provisions of this law, Virginia received three hundred thousand acres of land, which was sold by the Board of Education at ninety-five cents per acre, producing $285,000; and the proceeds invested in State bonds.” [University Catalogue 1872–73]

- Keep in mind that this was a segregated university system in the south, therefore ...

- ... two-thirds went to Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College [aka Virginia Tech] and “one-third of the money was allocated to Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute.”

- Why?

- Well, as mentioned above “the Second Morrill Act also forbade racial discrimination in admissions policies” but a “state could escape this provision...if separate institutions were maintained ...”

- This led to the creation of historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) and primarily white institutions (PWIs) within one state.

- [It’s important to note that “inequity in funding to HBCUs by states has been well documented since the founding of these institutions, and funding at these schools was very poor and not equitable compared to white institutions.” For example, Oliver Hill Jr., former professor at Virginia State University and son of notable civil rights lawyer, noted that their school colors “are orange and blue because we used to get the hand-me-downs from UVA for football.”] But I digress ...

- In 1872, Virginia Tech, formerly known as Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College, begins.

- 132 students attended the new college — tuition-free.

- Tuition free? Hurray for public education!

- Here’s how it worked: “The act of the General Assembly establishing this college provides that ‘a number of students equal to the number of members of the House of Delegates, to be apportioned in the same manner, shall have the privilege of attending said college without charge for tuition.’”

- Tuition exemption continues. From a review of university catalogues, it seems education was free for state students from 1872 through 1937. Then partial tuition was only charged for those students who did not excel academically (if you did well, all quarters were still covered). This practice lasted through at least 1960.

- So who primarily benefitted from a free education?

- Again, the student population at Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College was white / male from 1872 to 1920.

- Yet, in 1870, women accounted for 51.2% of the state’s population.

- And black Virginians “accounted for more than 40 percent of Virginia’s population” in 1872.

- It wasn’t until 1921, Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College began admitting women to the university for full-time studies. They were called “co-eds”.

- And finally, “in 1953, more than 80 years after its establishment, Tech was the first historically white land-grant institution in the former Confederacy to admit a black undergraduate, Irving L. Peddrew III, of Hampton, Va., the only African-American student among 3,321 white students on campus his first year.”

- So when it comes to diversity and inclusion, 1921 and 1953 are significant years, right?

- No, not exactly.

- Although admissions were finally open to women and students of color, enrollment staggered for these demographics for decades to come (and arguably still today). This may be referred to as “token integration” — marginal changes made to attain federal funds.

- In other words: Diversity doesn’t always mean equity.

- Then how exactly did “land-grant colleges democratized education, given that they did not fully include women, and the Morrill Act of 1890 also provided a structure that supported continued segregation of African Americans in the South”?

- Good question.

Interesting typography from the Catalogue of the Virginia Agricultural & Mechanical College, Session 1888-89, Special Collections and University Archives, University Libraries, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

VI. 100 years of Land Grant Universities — now what?

- With The Civil Rights Act of 1964 — which aimed to democratize higher education even further — marks ~100 years of land-grant education.

- This Act was significant because it “not only banned discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, but helped open the doors of Virginia Tech to a more diverse student population.”

- Promising, right? Well, let’s look at some graduation information.

- “Only three African Americans received degrees from Tech in the 1950s and just seven in the 1960s.” And ~50 African Americans received degrees in the 1970s.

- Keep in mind, this was a segregated educational system of the South, with partial funds going to an HBCU, but after 1964, public education should’ve opened up, right?

- You decide:

By the end of the 1960s, almost 50 years after admittance, women represented only ~11% of the student population at Virginia Tech

By the early 2010s, this grew incrementally to ~40%

Currently, it’s at 43% (AY 2020-21)

By the end of the 1960s, African American students accounted for less than 1% (.05%)

By the early 2010s, this was ~4%

Currently, it’s at 4.9% (AY 2020-21) - Alas.

- Just this year, a report was published which found that “student populations at the majority of Virginia colleges and universities were not representative of the state’s demographics.”

- This is not surprising. But striving to match state demographics is now not enough. Public education needs to serve the public — equitably. A university of the people, by the people, for the people. If it hasn’t, it needs to offer recompense.

- Dr. King was right — change needs to be “positive and massive”. But how?

- Consider this: The inequitable system of 1862 — is the very delivery system for change in 2022. It is in that structure, that fruitful cooperation between National and State Governments, that network of schools, that mission — to yield massive results. 112 institutions, immediately effected by one act. Just think of it. And since design programs often reside in land grant universities, designers may be in a unique position to enable such change — to organize task forces, to frame researchable questions, to visualize reparations — in order to shift policy, dramatically. It is perhaps through these design strategies, and a commitment to public schooling, that a decent education for all of our citizens may not just be a pursuit, or a proclamation — but a prompt realization.

This is not a history article. It is a design challenge.

Author’s Note: This essay honors all students, faculty and staff of land grant universities — regardless of gender or race — in celebration of public education and what Howard Thurman calls “reverence for personality”. Nevertheless, it strives to make a case for those who paid into the system in want of a decent education, yet were denied. It asks us to consider compounded loss from such educational withholding, the implications of this as generational deprivation, and the continued funding disparities in all aspects of university practice.