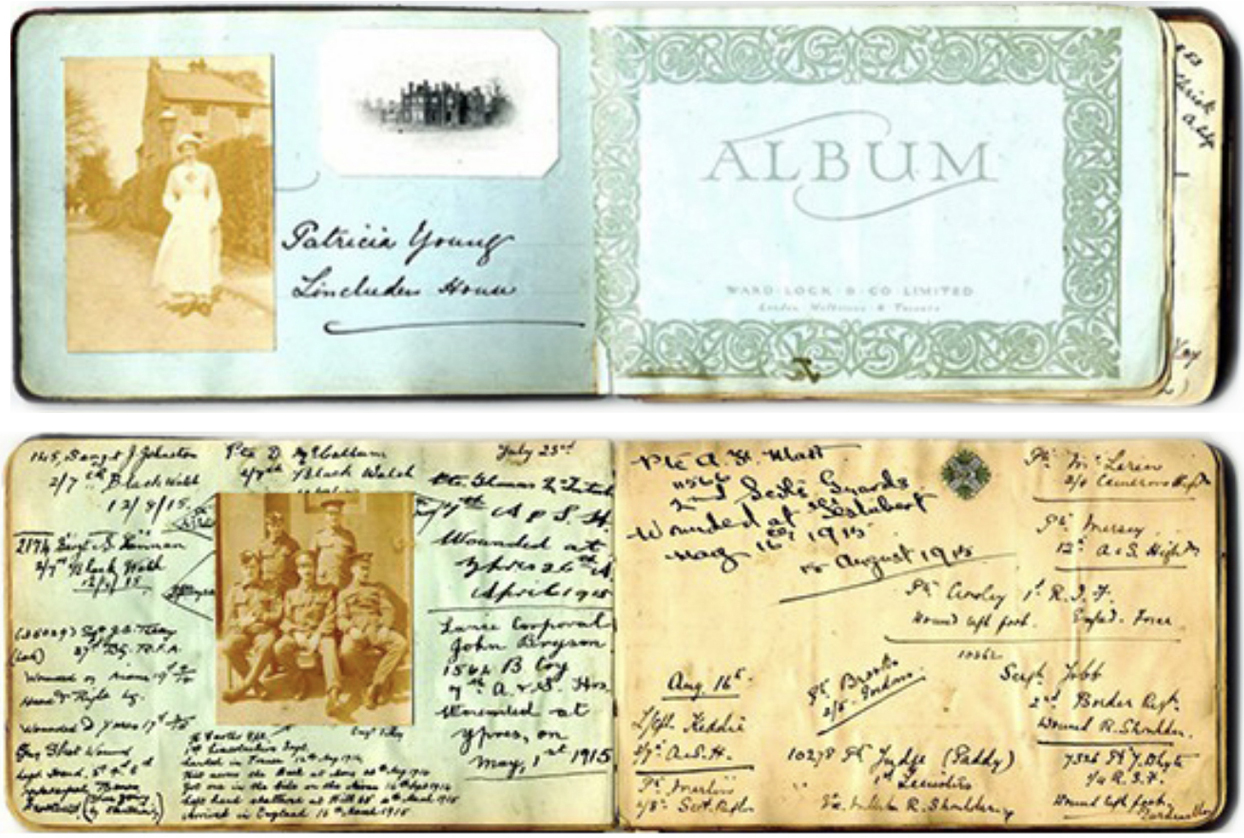

Autograph album compiled by Patricia Young, nurse of the Volunteer Aid Detachments, while stationed at a Red Cross Hospital in Dumfries, Scotland, during World War I. (Yale Center for British Art.)

To identify yourself in relation to a calamity is to reassert your own divine presence. This explains, in part, why certain kinds of (mostly autobiographical) efforts surge as creative responses during, and in the immediate aftermath of disasters, the keeping of journals and scrapbooks, for instance: they’re diaristic responses, impressionistic ways of capturing time’s unruly passage. You’re making work, marking time, and showing up as if to say—indeed, to prove—that you were there, and you survived.

Well done. But as you carpe that diem, you might be inclined to ask yourself how this helps someone else.

The purpose of life is not to be happy, wrote Emerson. It is to be useful.

Tricky.

As you make work that ratifies your connection to this moment, it is far too easy to submit to the dopamine surge that springs from the pure material evidence of what you are producing. While fitting, it’s also a false reassurance, which, while arguably great for you, might not be so great for anyone else.

Hard to consider this while in lockdown, which is perhaps why it looms so powerfully. And as difficult as this may seem—even counterintuitive for a column about creative practice—the journey of self-reliance requires a deeper exploration into something far more essential, and that is letting go of the supposition that the things you make are affirmations of who you are.

Consider this thoughtful observation from the late American theologian, Thomas Merton.

And I wind experiences around myself and cover myself with pleasures and glory like bandages in order to make myself perceptible to myself and to the world, as if I were an invisible body that could only become visible when something visible covered its surface.

To remove those bandages is to come out of hiding. This is an epistemic shift, to consider a new way of knowing yourself that might, in turn, yield some surprising dividends, including your ability to open your mind and heart to think about someone else.

It’s time to pierce the routine of the everyday. What else is there to know?

Lots.

Our strongest gifts, writes Parker Palmer, are usually those we are barely aware of possessing.

Sometimes studio practice needs to be less like a greenhouse (where we’re cultivating all that’s slow-growing and delicate) and more like a chemistry lab (where we’re experimenting and testing and blowing things up). It is only then, cleaning up the mess, that we see things for what they really are—which allows us to see what we need to do, and maybe that we need to do it for someone else.

Consider Nurse Patricia Young—not an artist—but a noble steward who served on the front lines during the First World War. Caregiver, photographer, biographer, confidante, and a devoted scribe with exquisite penmanship, she kept a pocket-sized notebook with her at all times to record all that she witnessed with her patients. Carpe diem? Yes, but with one big difference.

It wasn’t her own day she was seizing: it was theirs.

It’s not about what she made, but what she did. It’s not about being a nurse, but having a heart. And every once in a while, it’s not about looking, but about listening to someone else.

The best way to find yourself, wrote Emerson, is to lose yourself in the service of others.

Time’s unruly passage is not likely to change. But you can. And what an extraordinary thing it will be for all of us when you do.

The Self-Reliance Project is a daily essay about what it means to be a maker during a pandemic. Sign up to get it delivered to your inbox here.