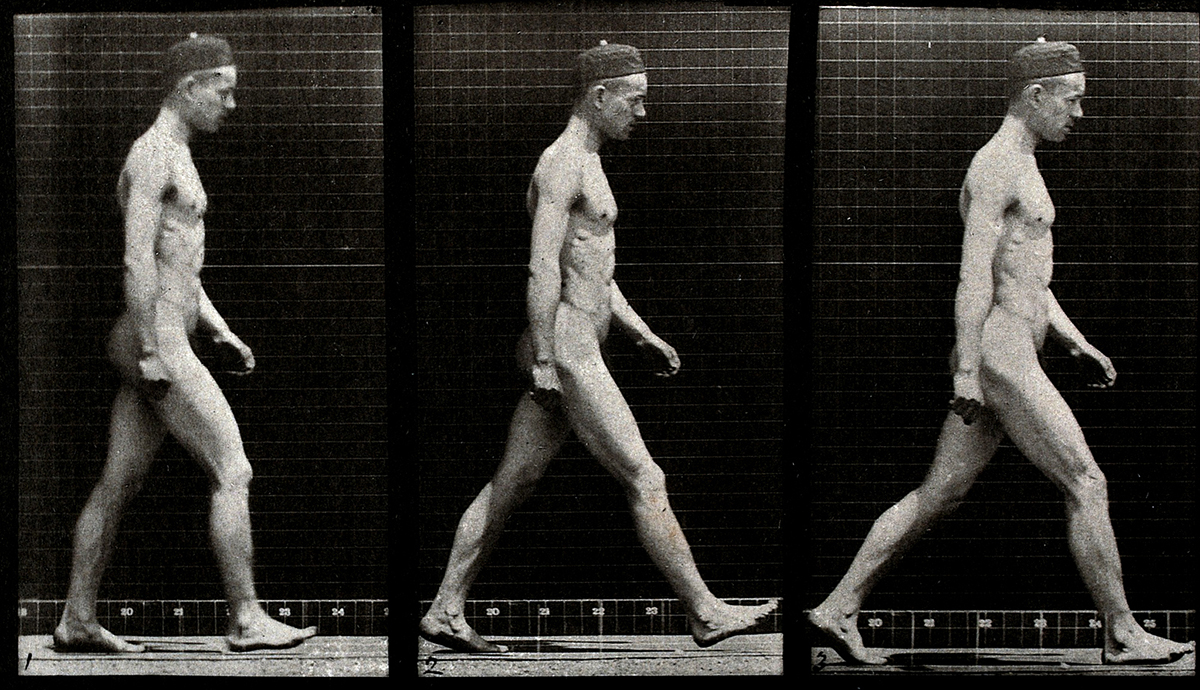

Man Walking. Collotype after Eadweard Muybridge, 1887. (The Wellcome Collection.)

The eighteenth-century Swiss philosopher Jean-Jaques Rousseau—whose Reveries of a Solitary Walker should be necessary reading for anyone suffering the existential pinch of protracted solitude—felt that his body needed to be in motion for his mind to feel free. Walking has something about it which animates and enlivens my ideas, he wrote. I can hardly think while I am still.

A Calvinist, pragmatist, humanist, and early advocate for equal rights, Rousseau viewed walking as a sensory practice, a form of active meditation. And he wasn't alone. From Kant to Kerouac, Robert Louis Stevenson to Rebecca Solnit, walking has long been seen, particularly by writers and artists, as a necessary and deeply creative act.

Even when you have nowhere to go.

My body is now going into its fourth week ricocheting around the same four walls, in my studio where I write and paint, eat and sleep, read, work, and think. It is also where I walk. I walk here seven miles a day, logging about fifty miles a week, without ever going outside. Does it matter that I’ve memorized the route, ending up where I started?

To walk without a destination allows your mind to wander freely, and invites your imagination to loosen its grip on duty and expectation. You can’t get lost, but you can venture freely, and far: it’s a form of creative trespassing, like tourism for the psyche. Only walking, writes the French scholar Frédéric Gros, manages to free us from our illusions about the essential.

Consider that Wordsworth clocked some 180,000 miles, on foot, during his lifetime. Emerson had rules (plain clothes! old shoes!) while Rimbaud was an obstinate, almost militant walker—unstoppable and fierce, a self-avowed professional pedestrian. Nietsche—who firmly believed that all truly great thoughts are conceived by walking—famously strolled unaccompanied for up to eight hours a day, stopping to scribble his notes as he did so. Robert Louis Stevenson thought walking (alone) opened your heart to all impressions, so you could let your thoughts take color from what you see. And Thoreau viewed walking—alone—as a form of personal crusade. You must walk like a camel, he once wrote, which is said to be the only beast which ruminates when walking.

Rousseau's own solitary essays read like a musical score, filled with rhythmic disturbances and circuitous pathways that seem to almost parrot the meandering unknowns of a delightfully unhurried stroll. He died before finishing them, but in a sense, a walk is never really finished, nor are the thoughts that accompany them, which are yours, and yours alone. Whether you’re hiking a mountain or looping circles in your studio, you always return to where you begin—an antidote, perhaps, to that existential pinch. Rainer Maria Rilke knew this well, and said it best. It changes us, even if we do not reach it, into something else, which, hardly sensing it, we already are.

The Self-Reliance Project is a daily essay about what it means to be a maker during a pandemic. Sign up to get it delivered to your inbox here.