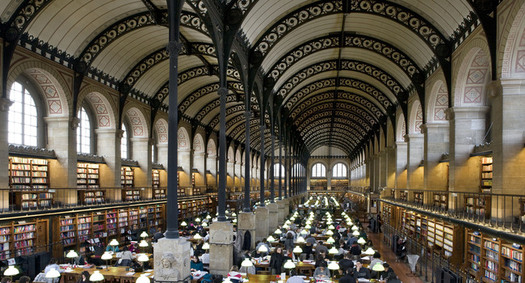

With the future of the New York Public Library the subject of so much public contention, there could not be a better time for MoMA's new exhibition on Henri Labrouste, the 19th-century French architect who invented the modern library as we know it. His two great projects — he built little else — are a pair of touchstone Parisian libraries, the Bibliotheque St. Genevieve and the Bibliotheque Nationale, that remain landmarks for their inventive structure, functional planning, and edifying design.

As curator Barry Bergdoll notes, Labrouste (1801-1875) worked through a period of extraordinary political and technological transformation. His were the first truly public libraries on a grand scale; that status reflecting the shift in power dynamics in Republican France. (The Bibliotheque Nationale was actually first conceived as the Royal library.) Architectural historians know him best for his introduction of iron work, heretofore the province of industrial typologies, as a design element in works of grand public architecture. His application of new iron technology allowed him to create broad, limpid spaces that would not otherwise have been possible. Their detailing, as the drawings and models in the show demonstrate, was extraordinary.

Labrouste was a draftsman of exceptional — mindboggling, really — ability. Today, the large-scale beaux-arts drawings of the type presented in this show are a thing completely of the past. Labrouste used them to chart the future. A pivotal moment in his life came during his travels through Italy as a winner of the Prix de Rome. In 1824, while visiting the three temples of Paestum, he came to see architecture as a discipline in the grip of perpetual development. This was a dramatic challenge to conventional wisdom, which then posited Classical architecture as an ideal frozen in time.

This philosophy, of an architecture of great generosity that constantly pushes technological boundaries, is just the kind of thinking we need today, especially as we reinvent libraries for a future that is as exciting as it is uncertain.

-@marklamster