WARNING: If you have not seen David Fincher's new film adaptation of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, read no further: spoilers abound.

In a post on his Front Row blog, New Yorker film critic Richard Brody remarks on the ferocious velocity of David Fincher's adaptation of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, a narrative momentum required to pack into the confines of a commercial thriller the great mass of material from Steig Larsson's sprawling, detail-suffused book. You can feel that visceral propulsion from the very first frames of the film's title sequence—an instant classic—with its driving Trent Reznor/Karen O rendition of Led Zeppelin's Immigrant Song.

As Brody writes, Fincher is liberated to set such a furious pace because the book is "so familiar that the details of its story can be flicked with a light brush and yet be fully and quickly grasped." Although there are drawbacks to this mode of filmmaking—too much critical narrative is dispensed with via exposition, as opposed to active storytelling—there is a compensatory pleasure in finding oneself in a kind of knowing dialog with Fincher. The idea that we have all read the book and so all know what is going on, allows Fincher a kind of postmodern freedom to turn the entire film into a reflexive comment on itself and the thriller genre. There are many moments in the film that are exaggerated to the extent that they call attention to themselves—Fincher upping the cinematic ante while letting you know he is doing so. That memorable opening sequence does this not just with its rushing score but with its visuals: bodies melting into and out of a viscous blackness, a dark inversion of the great Bond sequences we all know so well and that come readily to mind given the presence of Daniel Craig, the current 007, in the Blomkvist role.

Fincher's tounge-in-cheek tendency is unmistakable in the extraordinary torture sequence that comes toward the end of the film: As Martin Vanger prepares to dismember a suffocating Blomkvist, he flicks on his stereo and on comes Enya's Sail Away, in all its vapid cheeriness. Of course it's perfectly hilarious, and for a moment the end of any belief suspension. How did Fincher ever get Enya to licence that, you ask yourself? Certainly, you will never think about the song in the same way again. Or, more properly, Fincher has visualized precisely the state the song engenders. That's his joke with us.

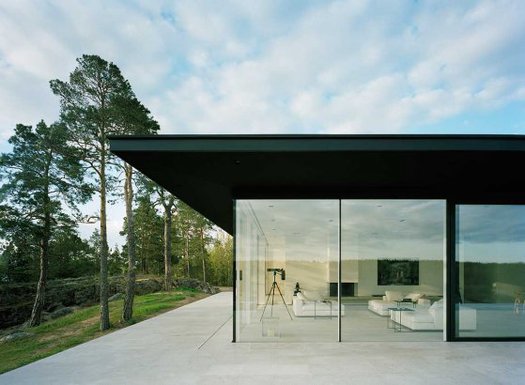

Brody also suggests that the film lacks "an element of the symbolic or the exuberantly garish." Here I would disagree, and point to the Martin Vanger house as evidence; this box of glass and black steel with white antiseptic interiors sets a new standard in Hollywood's long association of modern domestic architecture with evil. It is almost cartoonish—"exuberantly garish"—in its minimalism, a sense reinforced by the knowing clip of screaming wind that Fincher plays every time its front door slides open—another moment of Fincher elbowing anyone who's familiar with the book in the ribs.

It's worth noting that in Larsson's original the house is in fact described as modern and sparsely furnished, but it is also identified as built in 1978. Fincher has chosen something much more recent: as Architizer revealed earlier this year, the house is Jon Robert Nillson's Villa Abborrkroken in Överby, Sweden. Compare this very dogmatic home to that chosen for the Swedish adaptation of the same book: a considerably less provocative structure with a curving stone base. It is presented in that film as just a house, albeit a modern one, in a country in which the modern is not so stigmatized. That's a preferable reality, but in film sometimes tropes can be quite useful indeed.