Curators Jean-Louis Cohen and Mirko Zardini have already offered readers of Design Observer a glimpse at the camouflage section of their exhibition on architecture and World War II, "Architecture in Uniform." If that hasn't already encouraged you to visit the CCA, or at least purchase the show's excellent catalog, my review in the latest issue of AR should be another prod in that direction.

Among the primary themes of the show is the architect's role in the orchestration of overwhelming systems of rational management, sometimes in the pursuit of the most irrational malevolence. Cohen argues that it was the architects who could command immense bureaucracies who would dominate the profession in the postwar years, as would their modern style of building. As I write:

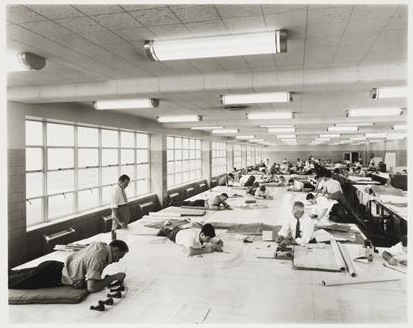

For Cohen, the great maestro of this technocratic revolution was Albert Kahn, whose Detroit office was a model of integrated industrial production. "Architecture is 90 per cent business and 10 per cent art," he said. A diagram of the "Kahn Organisation" - a tiered chart of administrators, designers, engineers and functionaries - commands a full wall. Kahn’s principles were applied worldwide - his office designed a tractor factory for Soviet Chelyabinsk - but it was in the US that they achieved almost transcendental realisation.Some 25,000 tanks were assembled at the office’s Chrysler Tank Arsenal, a massive bar with glazed windows. No detail was left to chance in the Kahn system. For the Ford Willow Run bomber factory, a vast facility that produced the B-24 Liberator, Kahn’s standard linear plan was given a dogleg shift to avoid it crossing into union territory.

Hitler’s grim campaign of aggression, enslavement and extermination demanded its own feats of infrastructural organisation. The architect Albert Speer was among the Führer’s most notoriously efficient administrators. Kahn’s dark mirror, however, was the largely forgotten Herbert Rimpl, who ran an immense firm building for the Reich, with outposts throughout the occupied territories. Like so many others who compromised themselves during the War years - among them, Auguste Perret and his pupil Le Corbusier - Rimpl emerged virtually unscathed during the aftermath.

While the show focuses on the technocratic and technical aspects of mobilization, I found myself thinking, counterintuitively, about the war's random and ungovernable qualities, which could be terrifying in their own distinct ways. This was the war that brought us Catch-22, SNAFU, and FUBAR. The week that I visited the show, I was reading Deborah Lipstadt's new history of the Eichmann trial. He epitomized this rational/irrational opposition. It somehow seemed fitting that he was tried in a glass box, a work of efficient modernist transparency.