Why did its authors hate the design of this book so much?

In 1999, I wrote a piece for Lingua Franca mentioning SMLXL (Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau) in which I naively suggested that, "Not since Robert Venturi's [et al] Learning from Las Vegas has the design of a book so eloquently expressed the point of view of its authors." Of course, I was speaking of the work of Muriel Cooper, the MIT designer.

Roger Conover, the architecture editor at MIT Press wrote me a long letter telling the true story. "Robert Venturi and Denise Scott-Brown [and Steven Izenour] found her design so offensive and anathematical to their ideas that they threatened to withdraw publication. There was a knock-down fight between Muriel and Denise, both of them refusing to compromise. The deal we made with them was to go ahead with the cloth edition as Muriel had designed it, and then let them design the second edition — the smaller book which is still in print and which bears very little comparison to the original edition with the glassine wrappers — which in Muriel's view DID reflect the ideas of the authors. But in the author's eyes did not. Perhaps because they could not see as well as Muriel [sic] could the monument that they were in fact building even as they of spoke of anti-monumentality."

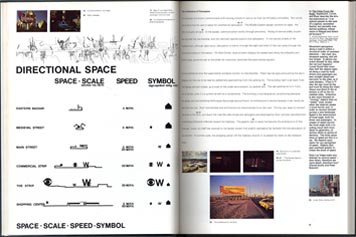

Thirty years after its original publication, Visible Language has created a special issue titled, "Instruction and Provocation, Or Relearning from Las Vegas." Among its (very academic) essays is this same story, retold by Michael Golec. Here, he casts a different net: an articulation of the "dynamic (or subjective)" in the 1972 edition by Muriel Cooper versus the "deadpan (and objective)" in the 1977 revised edition by Denise Scott-Brown. It took five years, but the authors got their way: a cheaper, more traditional edition that became a classic in classrooms. But it's also a less complex, less rich rendition of this seminal text. Ironically, the authors acted fearfully in the face of the very chaos that made their visual documentation so compelling.

An early example of the designer as auteur, this piece of design history is all about a book few have actually seen. Learning from Las Vegas (1972) is, after all, now a $3500 rare book. Meanwhile, the author's 1977 version is available for $13.27 as a cheap paperback.

There is further history here, as Muriel Cooper, who died in 1994, can be read both backwards and forwards. Forwards, she became the director of the Visible Language Workshop at the MIT Media Lab. (Janet Abrams reflects on her 1994 interviews with Muriel Cooper at MIT in the current issue of ID Magazine.) Her work with dynamic typography in three-dimensional space was the beginning of her impact on interactive design, and a decade later, her influence is still evident. (This Intel commercial by Imaginary Forces/Mark Zurolo is a case in point.)

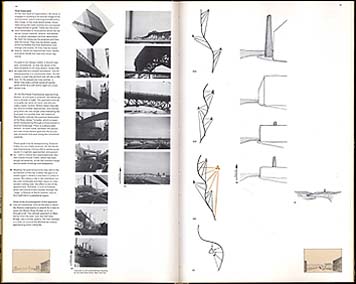

Her amazing interpretation of Learning from Las Vegas did not come out of the blue: even in 1964, she was exploring new forms of information design in her role as design director of MIT Press. Michael Golec smartly cites the example of The View from the Road, an important and visual study of highways in the American landscape. This book not only foreshadows her typographically complex and cinematic approach to the Las Vegas project, but it obviously is the source of inspiration for approaches later adopted by Richard Saul Wurman.

Learning from Las Vegas, as designed by Muriel Cooper, was a deeply layered experience befitting the underlying argument of this text. Whatever we think of postmodernism today, this book was a fundamentally radical design in 1972 — one that quite literally upset the apple cart of Swiss modernism.

Thirty years later, it still takes my breath away.

Spread from Learning from Las Vegas, 1972

Spread from A View from the Road, 1968