Photograph by Robert Lyon, courtesy of Daniel Friese

At the back of what looks like an enclosed porch of an unpretentious ranch house near Wall, South Dakota, a steel-runged ladder leads down a 30-foot concrete access shaft. At the bottom, a massive, eight-ton steel-and-concrete door is painted the red, white and blue image of a Domino’s Pizza box, with a slightly altered phrasing of the chain’s familiar promise: “World-wide Delivery in 30 Minutes or Less; Or Your Next One is Free.” But in this case the “Next One” is a Minuteman II intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). For almost three decades, the house was the “Delta One” Launch Control Facility (LCF) for ten Minuteman missiles armed with nuclear warheads. The massive blast door was designed to ensure that the underground launch control center survived a nuclear attack.

Welcome to the mordant, jingoistic and occasionally crude — but rarely before seen world — of “blast-door art.”

| Play Slideshow >> |

Like the garish and cheeky illustrations etched across the noses of World War II aircraft, these images in launch control centers across the United States testify to the bravado of the men (and, from the mid-1980s onward, women) of what has been called “America’s Underground Air Force.” But they also reflect the sometimes surreal pressures faced by two-person missile crews on 24-hour duty alerts, waiting for a call to turn their missile launch keys and perhaps end civilization as we know it. “You’re sitting there waiting for the message you hope never comes,” says Tony Gatlin, who painted the Domino’s homage as a young deputy flight commander at Delta One in 1989. “That’s a pretty screwed up way of looking at the world.”

Now an Air Force major and deputy director of staff with the 100th Air Refueling Wing, based at the Royal Air Force’s Mildenhall Base, in England, Gatlin was struck by the similarity of Domino’s delivery time and that of his missiles. “One went with the other kind of well,” he deadpans. Gatlin’s painting is one of only a few the public can see, following the transformation in 1999 of the Delta One control facility and the nearby Delta Nine missile silo into an historic site by the National Park Service (NPS). Under the terms of the 1991 Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty between the then-Soviet Union and the United States, many Minuteman missile sites have been deactivated or destroyed.

Photograph by Robert Lyon, courtesy of Daniel Friese

“The site is an exceptionally important icon from the Cold War era,” says Greg Kendrick, the NPS historian who led the effort to conserve it. He calls the decorated doors “imaginative and amusing artwork.” Though plenty of painted blast doors remain at missile bases in North Dakota, Montana and Wyoming (where some 500 Minuteman III missiles are still on alert), would-be aficionados can’t exactly wander in unannounced. It is thanks to Daniel Friese, a civilian employee at the Air Force Center for Environmental Excellence, in Brooks City-Base, Texas, that a visual record of the doors exists. Friese, who was in charge of cultural resources at Ellsworth Air Force base in South Dakota from 1993 to 1997, was a fan of Gatlin’s Domino’s knockoff. “We’d get to talking to the missile folks and they’d say, ‘Oh yeah, Delta One’s not the only one that has artwork — you should see the one at Foxtrot [another LCF],’” he says. “That’s what gave me the idea.”

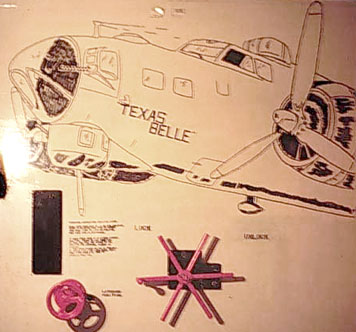

In 1995, he got a grant from the Department of Defense and, with photographer Robert Lyon, set out to capture this subterranean culture. “It was the greatest four weeks of my life, going to all these holes in the ground,” says Friese, who was trained as an entomologist. He estimates he has nearly 400 images from about 100 launch control facilities across the central and western United States, and is an authority on the genre. At Whiteman, for example, several cartoon characters (e.g., Road Runner, Oscar the Grouch) showed up, but so too did the squadron’s predecessor nose art. “They had taken a lot of the art from their B-17 squadron, the host squadron. That was a little different from Ellsworth, which was a little more freeform, if you will.” On several blast doors in the Whiteman squadrons, the actual B-17 is itself depicted; painted above the cranking mechanisms and the warnings to “Stand Clear of Door,” they bear replicas of the original nose art, with logos like “Texas Belle” or “Piccadilly Commando.” The latter, notes Friese, refers to World War II serviceman’s slang for the women who used to solicit in Piccadilly Square; the phrase “30 Bob,” also found on the blast door art, referred to the going rate.

The images in Friese’s collection are a jumble of regimental markings, cartoon character references (everything from Calvin and Hobbes to Captain America), and outright martial bravado. “There just seems to be a propensity for warriors to either mark their weapons or their territory,” says Friese. “Or it’s just boredom.” Striking too is the dark undercurrent of some of the artworks, skull-and-bones depictions or a grim reaper looming over the capsule entrance, scythe in one hand, missile in the other. “It was gallows humor,” says Friese. “It was like, ‘Hey, we’re defending the free world, and we don’t fear the commies. If it’s going to happen it’s going to happen, and we’re here to finish the job.’ I think that was the whole Cold War mentality.”

For previous generations of Minuteman crews, blast-door art might have seemed like something of a luxury. William Huey, a missileer at Whiteman during the 1960s, noted that blast-door art was an alien concept during his tour, the post-Cuban Missile Crisis days in which missileers still wore launch keys around their necks. “We had zero, zilch, nada door art, coats of arms, insignia at any site where I ever pulled alert. We had nothing but ‘Eye-Ease green paint’ as far as you could see, anywhere from the above-ground LCF to the underground equipment building and Launch Control Center.”

Even when it was allowed, blast-door art was rarely permanent. “There were times when commanders would go down there and say, ‘get rid of this stuff,’ when they didn’t want to see anything on the wall except official signs,” says Friese. When Brooke returned to Malmstrom recently for a reunion most of the artwork had been painted over, save for a single dog, now hidden behind some reconfigured equipment racks.

From the perspective of the “crew dogs” who pulled the 24-hour alerts, the artwork was a way to build morale for a job marked by routine, isolation, and fleeting episodes of very high anxiety. Missileers, after all, sat at the controls for missiles with megaton-range payloads, more than a dozen times more powerful than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima, aimed at strategic targets or population centers across the Polar Cap in the Soviet Union. (Gatlin still will not reveal his classified targets). The job was paradoxical: To perform successfully the real job that they were trained for — launching missiles — would in all likelihood mean they would never again see daylight. As Gatlin explains, “You’re doing a job that you hope you never have to do."

The images help us understand how the missile crews “handled a power that was capable of killing hundreds of millions of people,” says Jeffrey Engel, a cold war historian and consultant for the Delta site. The men and women who painted them tried “to use humor in order to cope with the dangers they were dealing with but also bring a little human emotions into a very dark place.”

Comments [22]

04.03.08

12:42

1.People do neat stuff in times of boredom.

2.Man will always find an active task to do when one is not given.

Thank you for the cool article,

CFair

04.03.08

07:26

04.03.08

08:21

The fact is that these missile crews played a vital role in keeping the peace during one of the most dangerous periods in human history. Deterrence worked.

In part it worked because both sides had rational leaders: who were death-averse and this-world oriented.

Today the main axis of tension in the world is between ideologies and leaders that/who are not death-averse and are next-world oriented: in other words, irrational. This is a far less stable situation than that which prevailed during the Cold War.

Our task now is to elect a national leadership that is rational, and that isn't looking forward to triggering Armageddon in order to fulfill God's plan. And it's interesting that one of the architects of the peaceful resolution of the Cuban missile crisis believes that McCain's legendary hot temper is a potentially serious issue.

It would be most interesting to ask the missile crews what characteristics they value in national leadership, a question they can answer without stepping over the boundaries of our our military's professional tradition to refrain from partisanship. We would do well to listen to what they have to say.

04.04.08

02:49

04.04.08

08:24

04.04.08

08:50

04.04.08

09:27

04.04.08

11:25

04.04.08

01:12

I love the questions you've posted. If you'll indulge me, I'll try to answer a few.

I'm not sure how old the folks are who've posted on this thread, but you've got to remember that it was a different era. Growing up during the Cold War, doing "duck-and-cover" drills in elementary school, certainly colored our world. The missileers (our preferred tag) I knew were proud to be performing the mission we were given. We truly believed we were making the world a safer place by going to work everyday.

For the most part, we were kids. I pulled my first alert on 10 November 1989 (I was 26 and was one of the "old" men... most were 22, 23 years old). For you history buffs, you may recognize the date. I went on alert the morning of the 10th of November, and when I emerged from the capsule the following morning, it was if we were emerging to a new world...the Berlin Wall had fallen that night. It was pretty heady stuff. No one really knew what to make of it. We figured it was a step in the right direction, but we still had the Soviet Union's (that's Russia to you youngsters) missiles aimed at us. We still had a job to do.

I could wax on for hours about this, but for the sake of brevity, I'll tell you I painted the blast door at Delta One the following month (December 1989). Dominoe's Pizza was still in its infancy, and the commercials announcing their 30-minute delivery garauntee were all over the television. That's where the idea came from (plus, the only paint we had on site were the colors of the pizza box).

For the other blast doors, some of them were based on WWII-era concepts. They came either directly from old units, or their aircraft, or were based loosely on them. If some of the art looks "Disney-esque" that's because Walt Disney himself penned some of the Army Air Corps' mascots back during the 40's. The originals of Disney's designs hang in the office of the Secretary of the Air Force.

Yes, it was pretty boring out in the missile fields. A lot of waiting around for what we hoped never came. Guess we had a lot of time on our hands.

No, the missiles weren't decorated. They were a sickly shade of seafoam green (about the same color of the banner on this page, as a matter of fact). No one touched them because of the highly sensitive nature of what they were. Plus, they were wired to set off an alarm in the capsule if they moved a fraction of an inch.

The launch codes and keys were locked in a secure box. None of the contents of the box was painted or decorated in any way. Again, too serious to touch.

The blast doors were really a line of no return. Once you entered the capsule, it was all business. It was ok to put art on the door, but once we were sealed inside, there were very strict rules about what we could and couldn't do.

Another interesting point is that the art in my squadron changed over the years I was on crew. When I first arrived, women had not yet been allowed to pull alert in my squadron. Some of the blast door art depicted nude women (pin-up fashion). Not long after women starting pulling alerts, the nudes got bikinis. By the time I left crew in the early 1990's, the bikinis had turned to one-piece bathing suits. There's an example of political correctness for you.

As for the post about our thoughts on politics and leaders...our job wasn't to reason why...our job was to go to work when the world needed us.

Anyway, I have to go for now. Thanks for your comments, and feel free to email me or post more if you've got more questions.

Tony Gatlin

Former Missileer of the 66th Strategic Missile Squadron

04.04.08

03:16

04.05.08

12:36

04.05.08

04:08

04.07.08

10:05

10.29.09

12:50

10.29.09

04:08

02.04.10

09:26

I adore this style of "underground art". It also paves the way for a wider audience who relate from different experiences and needs. I wonder if airplane wallpaper of the 50's and 60's was inspired by Blast Door Art!!!!

I enjoy reading the history of art movements. Art mimics the sentiments of that particular era and although Blast door

Art was born from violence I hear by the posts on this site that fun and humor was also a recipe for therapeutic relief.

Well done.

02.28.10

09:58

05.05.10

02:10

I painted three of works you have in your slideshow.

#3 with the eagle, and the pelican,

#6 "Peace through Strength"

and #10 "The Fighting 44th"

I was glad to lend a hand in putting some color down there.

Richard (Rick) Bridgnell former 67th SMS India Flight Commander

1984-1988

02.05.11

08:26

Missile duty was horrible. You were alone most of the time because your partner was asleep. Even though most silos had tv, most couldn't get any channels. It was cold. It was lonely. and it was stressful. Everyday you went to work it was with the knowledge that today might be the day you were called upon to blow up the world and end humanity, as we know it. And you had to believe that the task wouldn't be given unless our way of life was about to end. and most of us were between 22 and 26 years old, straight out of college, wearing butterbars on our shoulders.

As one of the first women, it could be even worse. If you reported the porn in the silo, you were ostracized. If you checked your knowledge against others just as a way of keeping yourself on your toes, you were incompetent. Women had only recently entered into some of the good old boy schools and we were viewed by many as less than equal. Wives had to give permission for me to go down in the hole with their husbands because I was "that heathen @+%*@* from hell here to steal my husband". I dont know how many times I was asked by tour groups and such whether I intended to have sex down in the hole. Paaaallllllleeeeeeaaaaassssseeeeee!

Anyway, I knew many of the art creators. They were interesting people. I never finished my tour because, as a newly married missileer, my civilian husband had the audacity to get me pregnant and end my career. The preemie baby had to come first and I had a commander who didn't understand those pressures. Told him I wouldn't turn keys and blow up the world, but I lied. Would have done it in a heartbeat, even today. I sometimes still dream about those days and going on alert. Never got to finish those four years and the af career because I was, unfortunately, the first woman to get married, get pregnant, have a preemie, request a discharge, get denied a discharge, and get railroaded out of the only career she ever wanted because of the men in her life.

DeAnna Lundergan Deneen, 68th SMS, Ellsworth AFB

First woman assigned to Lima Launch Control Center; First woman assigned to Kilo LCC, alternate command post; 1989-1991

. . . and I love the fact that my test word below for submission is "guffaw"; perfect, as sometimes, I just have to laugh at that silly girl who thought she could change the world!

06.09.11

09:13

Let's face it; assholes come in every shape, size, color -- and, of course, gender. While most female officers are solid professionals and decent human beings, the military had and still has an extraordinarily large proportion of militant, useless hardcore feminists with HUGE chips on their shoulders. When a crew of two is closed behind an eight-ton blast door several stories below the ground for 24 hours at a time, there are no witnesses. Whatever occurs on alert is one person's word against the other. During the era when women were beginning crew duty, the verdict quite automatically swung in the woman's favor, regardless of the issue. It was simply not a situation in which I was willing to place myself. Unfortunately, my following assignment was with the far more "progressive" 90th Missile Wing at FE Warren AFB. I had only one alert with a female crewmember; a really nice young lady who I knew well in my squadron. It wasn't a bad experience overall, but make no mistake; dressing, sleep shifts, etc. were simply an unnecessary pain in the ass with opposite genders in such a confined space.

The military is NOT a place for social engineering, or even equal opportunity. Whatever works best is what should be done. Bringing women on missile crew was absolutely pointless.

06.14.12

04:52

07.05.14

07:37