For years, Sylvie Meunier has collected vernacular photographs. Amateur and imperfect, they are her preferred materials—their banality a virtual blank slate for her assemblages, stories, and installations. In 2011 she received the Lo Pradal award at the Emergent Festival (Barcelona). Meunier has exhibited at the Photaumnales Festival (Beuavais) and at the Galerie La Jetée (Marseille), both in 2013, when she also was invited to participate in the Alwan 338 Public Art Festival in Bahrain. The series Avant que tu ne disparaisses (Before You Disappear) will be exhibited as part of this year's Mois de la Photo, in Paris, which happens throughout the city through the end of November, and alongside the annual Paris Photo fair this weekend at the Grand Palais.

This week John Foster interviews Sylvie Meunier.

What is your attraction to old, forgotten photographs and why do you think are they so moving?

I think there are a host of things that make these images so moving to me—I’ll explain a bit more in a moment—but mainly I think there’s something there in between mystery and familiarity. These anonymous images are by their very nature mysterious, since we don’t know the people in the pictures and we don’t know their histories, yet they share such a strong resemblance to our own family photos that they have the power to take us back to our own stories. I find that fascinating.

Snapshots hold a great deal of mystery, which is my personal attraction to them. Would you say that mystery, or the untold story, is yours as well?

I don’t see myself as a collector: I much prefer to consider the collection itself. To collect is an act of reassembly, of reunification and gathering. I rarely look for one thing in particular: rather, I look, observe, and sometimes stop on a certain image, either because its mystery draws me in, or because it’s so ordinary and common that my interest is piqued.

I go to flea markets and antique markets and have always loved old objects. And it occurred to me at some point that there were these enormous numbers of pictures that had been essentially abandoned by their owners. I find this odd and difficult to explain. There’s nobody interested in looking at them anymore, no one to explain who is in the photos, no one to talk to about them. It’s sad, and emotionally affecting, too.

So I wanted to tell stories with these images, to give them another life. I don’t know the people in these photographs, so I have to imagine, to invent them, I suppose. The pictures are like words that tell a story—perhaps even a little of my own story.

You are doing something quite different with your collection—you’ve actually created games with these images. I find this so interesting.

The games came about quite naturally, undoubtedly because I love playing games and it seemed obvious to make a game of seven families with all these family pictures! (Jeu Photo Des 7 Familles is one of the most popular games in France.) In addition, I found with these games an opportunity to share these pictures with people who might not have a chance to go and see my exhibitions of them. And the whole idea comes out of the this great tradition of parlor games—games you’d play with your brothers and sisters, your parents and grandparents. Sometimes, people tell me they find my games quite amusing and that the pictures remind them of people in their own families. That’s the power of anonymous images, to take us back to our own histories. I think that’s the part that excites me the most.

It appears from your website that you have created an entire line of photo-based products. Please tell us more about your line, Les Instantanés Ordinaires.

Actually, I produced the first “game of seven families” in an edition of 1000. They all sold out in just a few months. That made me want to create another game—The Photomemo—and a new game of seven families because I found that there weren't enough actual cards in the game if you wanted to play with more people at once. It’s much more fun when you have more people playing.

The name Les Instantanés Ordinaires does not specifically refer to these sorts of edited projects. I came upon it in the beginning when I’d just begun collecting these sorts of found photos and wanted a name for the collection. Les Instantanés is for the moments in a person’s life, and it also refers to the photography itself, the instant the photo is taken, for instance. And “ordinaires” made sense since the images that interest me the most are simple, communal, and yes, ordinary—the kinds we all have in our family albums.

This year I haven’t produced a new game: I’m getting ready for an exhibit and a book (Avant que tu ne disparaisses) that will be on view the month of November during Paris Photo.

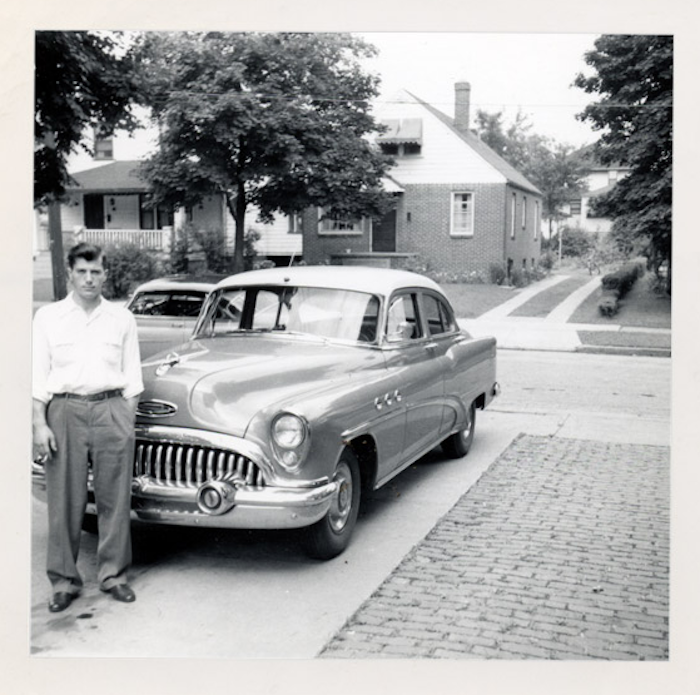

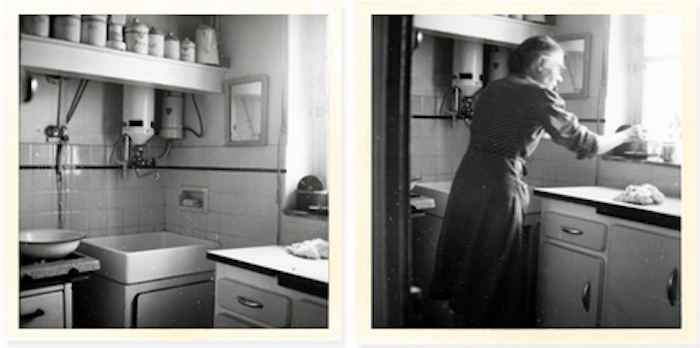

You have a series titled The American Dream. What do you look for in that series, as far as images are concerned? My thinking is that your selections represent a rather specific interpretation of that idea. Perhaps you could explain your point of view with this series?

It’s a series I am very fond of that will be exhibited next year in Belgium. I came up with it in collaboration with my husband, who is a photographer and who also loves old cars. We’ve been researching these images together.

What’s really captivating for those of us who are French are those images that look nothing like our family photos. These reunion photos were taken between the 1950s and the 1970s and seem to participate in a particular kind of American tradition: square format, men and women posing proudly in front of their cars and in front of their homes. They represent a certain kind of social success and seen together, they reveal, in spite of themselves (and unbeknownst to the person actually taking the photograph), the dream of American families in that era. The familiar simplicity of these images gives them a powerful symbolic value. They become, in a sense, icons for the American dream. But perhaps you see something different in them?